Concert pianist James Rhodes attempted to box his way out of the haunted, shadowy confines of childhood sexual abuse through drugs, drinking, cutting, cussing, constant self-harm, caustic relationships, and all manner of naughtiness. In the end, what brought him from funk to functionality — mind you, he’s still angry — was classical music.

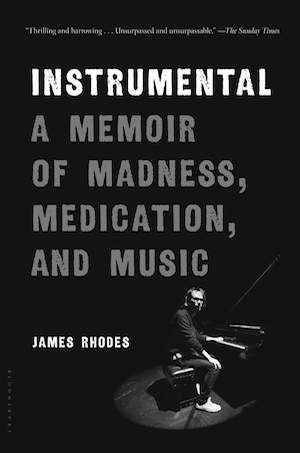

Importantly, Rhodes emerges intact as an adult in his memoir, Instrumental: A Memoir of Madness, Medication, and Music; displaying an independent spirit, scholarly integrity, marital gratitude for his wife, Hattie, and surprising fatherly devotion to his son. The London-based pianist’s metamorphosis from lost, suicidal soul to serious, complex artist is largely due to the 88 keys of a piano and concertos, symphonies, etudes, and the life stories of composers he adores: Beethoven, Bach, Chopin, Rachmaninoff, Prokofiev and others.

The raw tale told in his book that fought and in 2015 overcame a British Supreme Court ruling preventing its release by publishers Canongate in the U.K. and Bloomsbury in the United States, arrives unfiltered. Each of 20 chapters is paired with a musical selection and begins with a short essay that reveals dissonant, devastating or dazzling countercultural leanings of the selected composer. Remarkably, what could read as grumpy narcissism or too-close associations between mental illness and artistry — especially when Rhodes delivers in volatile language the full monstrosity of his experiences and behaviors — instead results in enlightened, uplifting literature about classical music and musicians.

The raw tale told in his book that fought and in 2015 overcame a British Supreme Court ruling preventing its release by publishers Canongate in the U.K. and Bloomsbury in the United States, arrives unfiltered. Each of 20 chapters is paired with a musical selection and begins with a short essay that reveals dissonant, devastating or dazzling countercultural leanings of the selected composer. Remarkably, what could read as grumpy narcissism or too-close associations between mental illness and artistry — especially when Rhodes delivers in volatile language the full monstrosity of his experiences and behaviors — instead results in enlightened, uplifting literature about classical music and musicians.

Rhodes was repeatedly raped and permanently emotionally and physically harmed by a physical education teacher, beginning when he was 5-years-old and a student at Arnold House, a prep school in St John’s Wood. Silenced by self-shaming thoughts, the abuse powered his inner world. Outwardly, it caused him to forgo formal musical education, forfeit early opportunities (a scholarship to Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London) and forge a unique, troubled, painful path to where he stands today, which is everywhere.

Rhodes has six top-selling albums, writes articles and books, performs international tours, and is himself the subject of documentaries. He’s also the creator of several television series. One explored music’s impact on people with schizophrenia and another connected to a campaign that provided schools in the U.K. with over £1million ($1.3 million) worth of instruments. Add to that his presence on YouTube and SoundCloud channels that attract over 10 million views, not to mention the 500,000 listeners who find his music monthly on Spotify.

Despite all that, Rhodes is not prone to proud display: he tilts toward t-shirts and sneakers as concert attire and talking with great humor (and profane prowess that some will find objectionable) to audiences before performing a piece. His philosophies and practice of piano border on obsession, as does his urgency to make use of his privilege, serendipitous and earned financial resources, and psychiatric support to speak out on behalf of disadvantaged youths and others who have suffered sexual abuse. With the 2017 publication of his memoir in the U.S. and in light of current social, political, and cultural movements, it was time to ask for an update.

In keeping with the sensitive material and subjects that are personal to Rhodes, his words from an email interview appear verbatim, lightly edited for length or clarity.

Given the #MeToo Movement in the United States, has that social and cultural reality altered the book’s reception?

I don’t think so, no. But I do think, finally, it has enhanced the reception that survivors of abuse receive. Finally people are starting to listen, really listen, and face up to the collective shame of sexual violence.

Sexual misconduct by people in power is not solely the domain of American life. What are your thoughts on the contrasts between the reception the book receives in the U.S. versus in Europe?

I think it’s a cultural thing. The [New York] Times for example was scathing of the book because of its swearing. Which is hysterical to me. For a country that elects a rape-y, xenophobic, bigoted reality TV star as its president and witnesses school shootings almost every week to be offended at the C-word is ever so slightly ridiculous. My experience is that Europe and Latin America is much more willing to open their eyes and see the reality of sexual misconduct, whereas America has its good, old-fashioned “everything is always amazing” hat on and finds it very hard to really accept the painful truth. Which is perhaps why the Weinsteins of this world survive so long even in broad daylight. America is a culture unto herself and I don’t think I’ll ever really understand it. We can buy Kinder Eggs in Europe but it’s very hard to by an AR17. Sadly, the opposite is true in America.

Instrumental isn’t a great book. But it’s got some good things about music and fatherhood, I think, and some valid points about mental illness and abuse that deserve to be acknowledged. But ultimately it’s a book about rape, classical music, and suicide and you’ll never find that in Walmart.

Did you have concern while writing the book that your story would alter the way people hear your piano performances and recordings?

No. Never. When people hear music, they experience their own feelings and history reflected back at them and not the performer’s.

There were legal battles as told clearly in the book. With the benefit of more time to consider the case and what it took to reach publication, what are the prominent legal limitations or practices you believe should change?

There were legal problems in different areas. The publication itself was a fight that took 18 months and cost $2M. Fucking lawyers. Luckily the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom saw sense, disagreed with people who said it was “too toxic” and allowed the publication to go ahead. With sexual crimes, there shouldn’t be any statute of limitations. It’s ridiculous to think that unless an 8-year-old reports a rape within 10 years then it’s too late.

You often speak in interviews and onstage of wanting to break down or at least set aside the high-art stuffiness associated with classical music. Would you consider putting out rehearsal recordings on SoundCloud?

I do Instagram Live videos fairly regularly. Honestly I don’t think rehearsal recordings would be that interesting to people. You wouldn’t want to watch a writer typing away and reading you rough drafts would you? Rehearsal recordings are very dull but also they’re misleading — often you’re testing the sound of a piano, the weight of the keys, practicing different rhythms and accents etc. You’re not playing the piece in the way you intend it to be played to an audience.

There’s lots of talk about how classical music needs to be “saved.” Your perspectives about not rushing for celebrity, trusting the moment and instinct, “fuck the lot of them,” and a return to the poverty-stricken roots of classical music are clearly described in your memoir. You also mention putting together your “own creative hub.” Will you please speak on these topics?

It [classical music] doesn’t need to be saved. Certain people need to be culled, perhaps ... I’m much more interested in bringing classical to places that wouldn’t normally have it. In a month I’m playing on the same stage and in the same festival as Rufus Wainwright, Kraftwerk, and Norah Jones, for example. And all 3,000 tickets have already sold out. Ditto the Sonar Festival a couple of years ago where I was the first classical musician to perform. Most classical musicians like to pretend what they do is much more valuable or important than other genres and it’s such bullshit. This music doesn’t belong to other people, it’s not High Art and it shouldn’t be like visiting a fucking church when you go to a concert. We all need to calm the fuck down and not take it quiet so seriously. The music mustn’t ever change, but the presentation needs to — urgently. Not to “save” it but to make it bearable for the 99 percent of the music-listening world who currently couldn’t give a shit about classical.