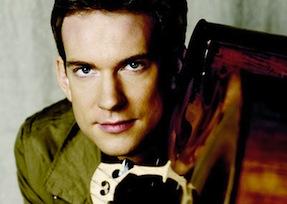

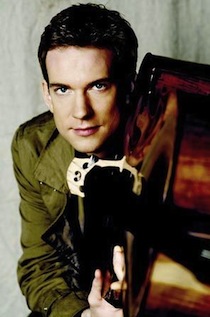

The cello has been Johannes Moser’s instrument since he was 8 years old, and he’s definitely one of the bright lights in the modern classical world. The electric cello is a much newer addition to the German-Canadian superstar’s instrument list, but San Francisco Symphony audiences will get a chance to hear him perform on one and, at the same time, will hear a premiere commissioned for him and the instrument at Davies Symphony Hall on Oct. 23. It’s part of the Symphony’s American Orchestra series; Moser will be performing the piece with the Los Angeles Philharmonic under its music director, Gustavo Dudamel. If you can’t catch him in San Francisco, see him on the Berkeley Symphony’s opening gala on Oct. 27, where he’s performing a different, but equally intriguing, program.

You’re performing the world premiere of Enrico Chapela’s electric cello concerto Magnetar this month, bringing it to San Francisco [with the Los Angeles Philharmonic] on Oct. 23 and 24. What can you tell us about this piece?

I’m super-excited about it. I’ve only recently been commissioning pieces for the electric cello. It’s great to be part of the first wave of development.

Chapela comes from a heavy metal background, so there’s a lot of distortion effects, pedals ... it’s going to rock.

How does an electric cello differ from an acoustic cello?

An acoustic cello produces sound with a wooden body. It’s a little box that can fill a whole concert hall. The electric cello has no body, so there’s no sound on its own. It requires effects: amplifiers and software on the computer to modify the sound.

Why did you start playing the electric cello?

I was learning the acoustic cello and, being a true perfectionist, I needed a musical playground. I could be experimental and playful without being criticized and measured. I have the freedom to play. I’ve always wanted the chance to dive into other parts of the sound world, and this is the best of both. I’ve reached the stage now where I feel comfortable sharing. At first, I was trying not to be just a bad electric guitar or electric bass [player].

Music can provide soul food. It has a huge impact on people’s lives.

You have a reputation for choosing lesser-known repertoire, and new music. What draws you to these pieces?

I was a little frustrated. People say the cello repertoire is limited. After 10 years of looking, I think the perception is limited. People should be open to this music. There are some true gems. I’m a strong advocate. I’m lucky that my increasing status allows me to bring out this repertoire and share it.

You’re also involved with reaching young audiences. Do you approach younger audiences differently than you would traditional classical concertgoers?

Absolutely. You get an immediate response. They’re super-honest. It’s either “Wow, this is fantastic!” or “This is terrible!” As long as there’s an emotional response, I’ve done my job. The worst thing for any performer is when the reaction is indifferent. When I go into a school, I want to provide that initial spark so people can take up an instrument, even if it’s only for a couple of years. They can actually touch a piano or a trumpet or a clarinet. If there are 30 kids, I hope to inspire four or five to look for more music in their lives.

It’s especially important as funding for arts in the schools is getting cut.

Berlin [Moser was born in Munich] is chronically broke and the arts are the first to go down the drain. Orchestras, performers, and soloists have to do what they can. In the 21st century, performers are shifting from only [being] artistic to doing artistic/social work.

Music can provide soul food. It has a huge impact on people’s lives.

Why did you start playing the cello?

I needed a good reason to get away from the violin. Coming from string instruments, the cello made sense. I sat down and immediately could feel those lower registers. Of course, as an 8-year-old, you don’t really put it that way.

I’m always looking for artists who try to push their boundaries and the boundaries of music, who leave their comfort zones.

When did you start playing the violin?

I was 5 years old. When I look at pictures, I see a miserable kid with the violin. The cello did something for my confidence. When I was 15 to 16 I hit a rough patch, as everyone does, and it was kind of like I always had a friend.

What other instruments do you play?

I play horrible piano. I’m always interested in finding weird percussion instruments. I guess I could say I play computer music. I use my computer for effects and modifying sounds. It’s my third instrument.

What instrument would you like to play?

I’d love to be a good singer, when I see what is possible to do with the voice. I had one lesson with my mom [Canadian soprano Edith Wiens], and we had to stop after five minutes because she was laughing so hard.

Everything in music comes down to the voice and percussion instruments. They’re the answer to almost every musical question.

What would you do if you weren’t a musician?

I was into theater for a long period. I wanted to be a director. I was fascinated by the work the director was doing. Now, I’m a director and interpreter of music, so it’s quite close. I try to make people see the piece through my eyes and hear it through my ears. It’s part of making it your own.

Of course, as I kid I went through the usual careers: pilot, private eye, go into outer space. But “director” was always there. Now I get into cabs and talk with the driver about playing my cello, and then they always ask, “What do you do for a living?”

I know you’re a mountain biker, and crossed the Alps on a recent bike trip. Where did you go? Road or dirt? What was the trip like?

We went from Garmisch in the southern part of Germany through Switzerland to Italy. It was on dirt, and took six days. I was thrown into a group of mainly guys about my age who had never heard a classical concert. I was without my instrument. No one knew me. It was a refreshing and new experience. I knew they liked me for me, rather than what I did.

Biking is a wonderful speed for watching the scenery change, but not too quickly, like in a car. I would like one of those reclining bikes. It would be great for my hands. Personally, it was an accomplishment. I was training for eight months. I took those experiences into my professional life, learning to prepare over a long stretch of time, like for my work with the Berlin Phil.

What are your other hobbies?

When traveling, there’s a lot of time wasted in airports. I love to read. I’m not a fast reader, but when traveling I can get a lot read.

Everyone thinks you have a lot of free time, if you’re a musician, after you practice. But I spend about two or three hours every day on e-mail, I contact composers, I think about new programs.

What are you listening to?

I’m learning the [premiere] piece and listening to music that Chapela’s suggested, mainly heavy metal. I like jazz, especially free jazz of the ’70s, like when Miles Davis went electric. It’s a rough experience. I’m always looking for artists who try to push their boundaries and the boundaries of music, who leave their comfort zones. It’s something I can relate to with the electric cello.