While Mark Morris is best known for his dancing and choreography, this September Bay Area audiences will have a chance to see him in the role of conductor when his Mark Morris Dance Group joins the Philharmonia Baroque Orchestra and Chorale, mezzo-soprano Stephanie Blythe, baritone Philip Cutlip, sopranos Yulia Van Doren and Céline Ricci, and tenor Brian Thorsett for the Cal Performances presentation of Dido and Aeneas. Morris’ choreography for this Purcell opera is considered one of the classics of modern dance, and it’s paired with Blythe’s Cal Performances debut. It promises to be an exciting evening of music and dance. Morris, as always, has strong opinions on both conducting and dancing, which he was willing to share with SFCV.

You began conducting in 2006. Are you fully comfortable now in front of an orchestra?

Sure. I wouldn’t do it if I wasn’t comfortable. It’s terrifying. But I’ve known the [Philharmonia Baroque] orchestra for 25 years, and they’re friends. Also, it’s much easier to conduct an orchestra that’s very, very good. But eventually you have to give the downbeat.

How is it different from dancing?

It’s an entirely different thing. You’re not performing, but instead you’re encouraging other people’s performances. Your back is to the audience. I like having my back to the audience.

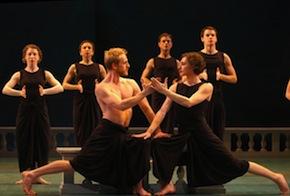

Photo by Stephanie Berger

You can’t stop and listen. Otherwise, everything else just stops. You can have rehearsals, but once you’re in performance, there’s not much you can do.

What’s it like participating in a MMDG performance from the pit instead of onstage or watching it from the back of the theater? Are you still connected to the dancers?

You can’t really watch much, though if it’s going well, you can see some of it. I don’t do much watching. I’m trying to keep people together. Sometimes I get a look from the dancers, much like I used to give, to pick up the tempo, and I’m: “OK, I’ve got it.”

How do musicians vary from dancers in how they approach their work and how they work with the conductor?

When I work with musicians, especially a lot of young musicians who’ve done a lot of learning but not performing, they don’t realize that it’s a physical job. They think that it’s in their head and that they’re simply using the instrument to bring it out. And they don’t realize that they have to “corporealize” and participate with their physical body. They may not be moving around, but they’re using their physical body to transmit the music.

Young musicians may not be moving around, but they’re using their physical body to transmit the music.

You’ve danced the Dido/Sorceress role yourself. When you guide a dancer through a big, emotional role like Dido, do you find yourself refining or changing your conception based on what the dancer brings to the role?

No. The text is there, and it doesn’t change. I use the people in my company, and they can do the dance. I don’t change it. There are bits in Dido that are freely improvised, like the witch dances. I tell the dancers to think of something and do the opposite! But everything is so strictly built in rehearsals that they are then free to improvise in performances.

How do you keep your repertoire fresh?

We keep things fresh by lots of rehearsals. Right now there are 25 pieces that are up and ready to perform. Dancers always have to memorize, but having so many pieces helps keep things fresh. Also, we only work with live music, so every performance is different.

When you bring dancers into the company it’s often after they’ve danced with the company. How does that work?

I hire apprentices, then after six months I hire them as members of the company, extend the apprentice period, or let them go.

There’s a huge array of classes at the Mark Morris Dance Center. Is that part of your philosophy of teaching dance?

There are lots of classes, teaching what people want. Most are little kids. It’s a big success.

Do the different styles affect your choreography?

Styles are offered but they don’t influence my work as a choreographer. That’s from me. Zumba, it’s a workout. People don’t realize that Pilates, yoga, Zumba — they’re also ways of thinking and moving. Still, it’s fun, and it tricks you into exercising.

We keep things fresh by lots of rehearsals. Also, we only work with live music.

So you won’t be taking a Zumba class?

No.

I also notice that the school teaches a class for boys only. It’s great to champion boys.

I champion all dancers.

How did you get started as a dancer?

Every kid wants to dance, but at about age 8 or 9 — I guess 9 — I wanted lessons. My mother found a dancing school, and that was it.

It seems to have worked out.

It better. I don’t know how to do anything else.

You’re a MacArthur Fellow. I spoke with Marin Alsop about being a MacArthur Fellow ...

She’s great!

She said it was a complete surprise, and surreal.

It was a shock. You can’t apply, and it’s fully secret. I thought it was a joke.

Every kid wants to dance.

What are you looking forward to with this performance, in addition to working with the PBO?

I’ll be conducting the great Stephanie Blythe. She’s a good friend. I’m very excited. She’s one of the great, if not the greatest, singers of our times. It’s a little terrifying. She’s very formidable: smart, colorful, and fabulous. Rehearsals should be interesting. And short.

The dancers have done this many, many times, and it’s wonderful to do it again. And Nic [Nicholas McGegan, music director of Philharmonia Baroque] is a good friend.

In an interview I read, you said you thought more young people were going to the opera. Do you think that’s true of all the classical arts?

I think so. But, people should read more. Shut up and read.

Boundaries are shifting, which is good, though it threatens to be dilettantish. You don’t learn quite enough. It’s nice to go deeper into one area, not just covering the surface. For example, before you start making antireligious statements, you should read the Bible. I’ve at least read the Bible.

What do you want audiences to know about this performance?

It’s an opera, not a modern dance. Every element is of importance, as it is in opera. And should be done well. People say the orchestra is not important in opera because it’s in the pit, but that’s just because there’s no room on the stage, Plus, it’s easier to understand the singers if you can see them. You have to look at the big picture, including the musicians. Come ready to watch. Not to text.