Last month, San Francisco marked the 30th anniversary of the 7.3 magnitude Loma Prieta Quake, the biggest shaker since 1906. And, on Sept. 5, 2027, it will be 30 years since the reopening of the War Memorial Opera House, rebuilt after being damaged in the 1989 quake, and thereby hangs this tale.

How did SF Opera continue to use the quake-damaged War Memorial for seven years before closing it for almost two years for the reconstruction? How did singers, musicians, and we-the-audience carry on from 1989 through 1996, night after night, sitting under a net stretched between us and the Opera House’s majestic (and pointed) chandelier, being “protected” from pieces of rubble expected to fall. Nothing big fell and we survived.

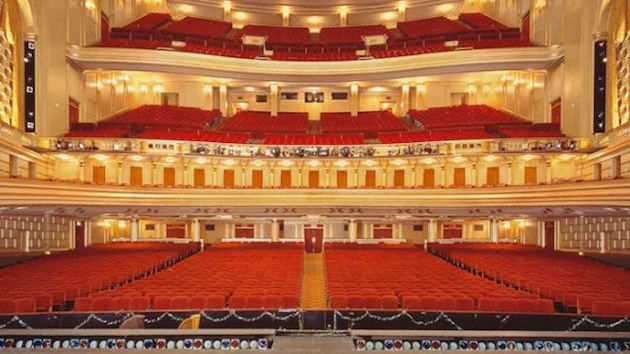

Anthony Barcellos recalls: “I remember sitting in the balcony and looking out across the ceiling net, inspecting it for debris, spotting only the tiniest chunks of material. Fortunately, the dangerous-looking chandelier stayed in place.” A good thing, because the Phantom of the Opera-scary chandelier is 25 feet wide, 14 feet tall and is fabricated of cast aluminum decorative elements that are attached to the building steel. Oh, and it has 588 light bulbs.

Perhaps the most memorable fact about SF Opera’s quake heroics: three days after Oct. 17, 1989 — with the Bay Bridge down, casualties still explored in the Marina and Oakland — the company schlepped as much as possible across town and performed Otello in the Masonic Auditorium.

Aida followed the next day, on Oct. 21, and then Idomeneo, which was the scheduled show on the night of the quake. And then, led by General Director Lotfi Mansouri (who spent the quake’s 15 long seconds under his desk in his Opera House office), the company returned to the War Memorial on Oct. 24, performing Otello.

This all transpired as the city was still in shock after the quake, a day described by Sabrina Adler, daughter of the company’s late general director:

I have a vivid memory of being mid-rehearsal with the San Francisco Girls Chorus on Oct. 17, and all of a sudden hearing a loud jackhammer-like noise, accompanied by lots of shaking. We then went into the courtyard of the church where we were rehearsing and the older girls sang to the younger girls to comfort us.

We had heard that the Bay Bridge had fallen down (the specific information about it only being a small section hadn’t reached us) and many girls had parents who were en route from the East Bay to watch us do a mini performance at 5:30 p.m. (the earthquake was at 5:04). There was a lot of panic as a result.

My mom eventually arrived to pick me up and we drove back across the Golden Gate Bridge to go home. I remember looking from the bridge at a pitch-black dark city [the power was out everywhere] as the sun was setting. The only light came from the fire burning in the Marina. It was eerie.

By 1996 another, much longer, trial faced SF Opera as the consequence of Loma Prieta: It became the first large opera company to have a season (and a half) without a home.

Raising the needed $90 million (when that was “real money”) was just the beginning of Mansouri’s saga of the survival, or better yet, the flourishing of the only major opera company ever to conduct regular seasons without its home.

Finding temporary locations for productions around town, Mansouri oversaw the 21-month renovation of the Opera House from bottom to top (not the other way around), called officially “a complete seismic retrofit.” A magnificent staff and managers such as Executive Director Michael Savage assisted Mansouri, while the architectural, engineering, and construction teams executed the project amazingly well, overcoming the setback from a four-alarm fire in May, 1996.

Among memories of those months:

-

Prince Igor, Tales of Hoffmann, Salome, Aida, Fledermaus, and Lohengrin in the Civic Auditorium (not yet named for Bill Graham)

-

Hamlet, Barber of Seville, Harvey Milk, and the “Broadway Bohème” in the Orpheum

The Opera House reopened on Sept. 6, 1997, with a gala concert celebrating both the occasion and the 75th anniversary of the original War Memorial. Beverly Sills hosted the evening, Sir Derek Jacobi was the master of ceremonies, and featured artists included Placido Domingo, Marilyn Horne, and Frederica von Stade.

An unforgettable scene that night was described in a New York Times report:

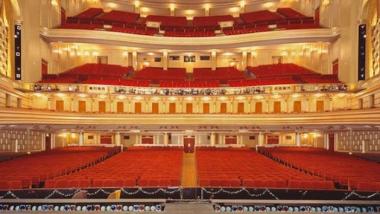

As the audience entered the auditorium, the house lights were dim, complicating the task of finding seats. But the reason soon became clear. When Donald Runnicles, the company’s music director, commenced the evening by conducting the orchestra in the national anthem, the lights suddenly brightened with the line ‘‘And the rockets’ red glare, the bombs bursting in air,’’ revealing, to oohs and aahs from around the house, the stunningly regilded interior with its repainted ceiling of aqua blue, flecked with clouds of white, and the glittering chandelier. It seemed a typically theatrical California gesture, but it certainly worked.

And we’ve lived happily ever after.