When the curtain goes up on San Francisco Opera’s current, acclaimed production of Britten’s Billy Budd, which is performed through Sept. 22, the crew of HMS Indomitable is not climbing up and down the masts — mizzen or otherwise. They are all scrubbing the floor or, I am told, “holystoning the deck.” What’s going on?

SFO Chorus Director Ian Robertson, himself a scion of seafaring Scots, explains: “Holystone is a soft and brittle sandstone that was formerly used in the Royal Navy and US Navy for scrubbing and whitening the wooden decks of ships. The term may have come from the fact that ‘holystoning the deck’ was originally done on one’s knees, as in prayer.”

Explains Billy Budd revival director Ian Rutherford:

The score and the libretto for Billy Budd are both very clear that the crew are holystoning at the beginning of the opera. This arduous task, authentic in 1797, was performed every day. On the bigger ships, it was done with a number of very large stones pulled by ropes but on a smaller ship the crew had to get down on their knees and scrape the boat deck.

The reason for this was that salt deposits as well as other deposits would build up. If left alone, these deposits would make the deck impossibly slippery. The stones were shaped like Bibles and the crew were on their knees, thus the nickname “holystoning.”

That’s just one of the countless details the Glyndebourne and San Francisco stagings of Britten’s opera required, and it was realized splendidly.

The biggest, most obvious aspect of staging is the enormous set itself, in Christopher Oram’s sensational set design and in Paule Constable’s exceptional lighting design for Michael Grandage’s production, both well-served by revival stage director Rutherford and revival lighting designer David Manion.

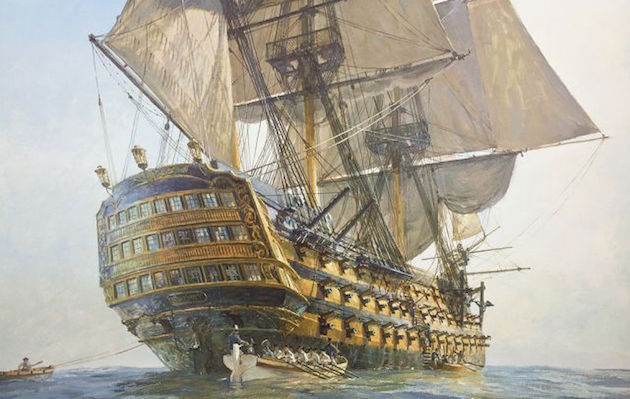

Of the acoustically splendid “ribcage” set from Glyndebourne, Oram said: “The shape is evocative of nautical architecture (curves, warm wood, tiers, galleries). Grandage wanted to make the audience feel like they are ‘on the vessel.’ When Vere stands on the quarter deck commanding his ship, he commands the entire auditorium.”

At the same time, the set conveys the feeling of the claustrophobia and darkness below decks, “the body of the ship to be like the belly of a whale,” as Oram put it.

SF Opera Executive Director Matthew Shilvock has been preoccupied with the Billy Budd production for a long time, regarding it as a special project after a 15-year hiatus in both the opera’s and Britten’s presence in the War Memorial:

“There is something so intense, so perceptive, so dynamic about Britten’s music and this particular production provides a stunning frame for this emotionally charged world to unfold.”

Shilvock and Oram explored the design of an 18th-century man-of-war ship on the stage:

The nautical and theatrical worlds are not so far apart. There’s an important word that connects us both: “rigging.” Sailors with highly developed skills in rigging ships found excellent onshore work possibilities in theaters where the flying system of ropes and pullies came very naturally. That interconnectedness became the very basis of this production of Billy Budd, originally designed for Glyndebourne in 2010.

When Glyndebourne commissioned the production, they did not propose a specific aesthetic; rather what you see is their interpretation and perspective on the piece.

Christopher refers to himself as a classical and textual designer — someone who seeks to deepen our connection to the work as created by composer and librettist, not someone who cuts against those intents. He knew that he wanted to find an aesthetic world that supported Benjamin Britten’s story, and one that allowed us into an 18th-century man-of-war and all of the detail that Melville conjured up in the novella.

The production is big in personnel as well as in physical staging: 23 principals, 40 chorus, offstage and children’s chorus, dancers, supernumeraries — 81 in all. In the pit: 73 musicians, plus four onstage drummers.

As to all that roping Shilvock mentioned, stage director Rutherford said in a Bay Crossing interview that “yards and yards of authentically made rope ... was made for us at the Chatham Master Ropemakers, where they have been making rope in their quarter-of-a-mile-long rope shed for over 400 years.”

In the production, miles of ropes are pulled and tied, especially in the first scene and in the battle, showing the effort required to pull up the sails.

The SFO Chorus, as the crew of the HMS Indomitable, had to learn not only holystoning, but also how to tie bowlines and clove hitch knots, and to load cannon balls.

Oram’s inspiration for the set, Shivock says, came all the way from his childhood: “As a young boy growing up in Sussex (the county where Glyndebourne is located), he visited the HMS Victory, the ship used by Admiral Lord Nelson to defeat the French at the Battle of Trafalgar. He also has a visceral recollection of an exhibit at Madame Tussauds waxwork museum in London that used early multimedia effects of light, smoke, and even smell to create the sense of Nelson’s ship.”