The Mass was by Joseph Haydn, who’s been the subject of commemorations this year — May 31, a week ago from last Sunday, was the 200th anniversary of his death. The specific work was his “Lord Nelson” Mass, more formally known as the Missa in Angustiis (Mass in troubled times). And when doesn’t a title like that resonate with contemporary concerns? It’s one of Haydn’s last works, written under the influence of the Handel oratorios he’d heard on his visits to London, updating that composer’s aesthetics to his own time.

The other works on the program had similar resonances. Sergei Prokofiev’s Classical Symphony was written as a lighthearted speculation of Haydn’s spirit, updated to Prokofiev’s day in the 1910s. Scott MacClelland’s program note cites reminiscences of Beethoven, Rimsky-Korsakov, Glazunov, and Stravinsky in the work, as if he thinks they invalidate that premise. Who’s to say, though, that Haydn in the 20th century wouldn’t have picked them up along the way, especially if he’d moved to Russia?

Peter Ilych Tchaikovsky’s Serenade for Strings bears a similar relationship to Mozart, Tchaikovsky’s favorite composer. Mozart had more of the seeds of a 19th-century romantic in him than Haydn did. Had he been writing serenades in the 1880s, like Tchaikovsky, instead of in the 1780s, they might have sounded something like this: same emotional effect as Eine Kleine Nachtmusik or the Gran Partita, more openly expressed with fuller harmonies, and still with a strong sense of classical form.

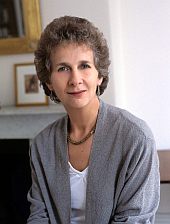

Under Jane Glover’s baton, all three works shone with a brightness and immediacy that easily reached up into the balcony where I was sitting. It’s not that the tempos were fast — the Prokofiev and Tchaikovsky, in particular, were presented with a slow deliberateness — but rather that the playing was clear and emphatic and that each note was touched with precision. Either SSV has found a new and superior adjustment for its acoustic shell, or else Glover’s conducting inspires the players to vividness.

I suspect it was mostly the latter. The cellos, often SSV’s problem section, were more solid in intonation than they typically are, though the strength of their playing was sometimes still weak.

The performance of the Prokofiev interestingly echoed SSV’s rendition of Shostakovich’s Ninth Symphony in March. (In sympathetic vibration, perhaps, the Classical Symphony, which was Prokofiev’s First, was misnumbered 9 in the program book.) The outer movements sounded a bit rough, but the whole held together, in a pointillistic performance emphasizing staccato notes and accents.

The Tchaikovsky was about as similar a performance to the Prokofiev as the composer’s smooth lyricism would permit. Although Tchaikovsky’s harmonies are rich, that doesn’t mean they have to be lush. There’s room to eschew that in a work like the Serenade, here played in a lean, “stringy” style, with slashing chords and thumping pizzicato. Combined with care and deliberate tempos, it made for a rewarding interpretation, with especially lovely sound elicited from the violas.

Overly Massed Chorus

On to the main event, Haydn’s Mass. The Symphony Silicon Valley Chorale, directed by Elena Sharkova, is not a particularly large chorus — 75 were on stage — yet they overwhelmed the instrumentalists in sound as well as in numbers, despite the inclusion of the (inauthentic, according to my sources) wind parts in the orchestra. All four sections of the chorus sounded both confident and strong in this performance.One thing Haydn may have learned from Handel’s oratorios was how to make a static vocal work into a dramatic entity. The Missa in Angustiis is in an angry D minor. It churns and pounds, and while the solo parts are not extensive, they provide much opportunity for their singers to express character. This performance had four highly distinctive people up front. Christine Brandes, an amazing soprano, had the most solos and stood out most strongly. Her voice is so strong and carrying that it pierces like a laser beam through any instrumentation that Haydn or his arranger cares to throw at us. Yet her tone is not thin or shrill. She has breadth and command. Brandes was a wonder, and this was just the work to display those talents.

Paul Murray is an appealing bass-baritone. His voice, while deep, is light-toned and has a fine-gritted texture, like the string instruments in the Tchaikovsky. Tenor Brian Staufenbiel, strong and elegant, and mezzo Raeeka Shehabi-Yaghmai, another spacious voice, full of the vibrato that Brandes largely eschewed, had less to sing, though they held up their ends with comfort.

The one thing Haydn did not pick up from Handel in this work was a sense of contrast. This Mass batters the listener, and it’s all like that. Most of the music is fast, and even the occasional slow movement provides no relief. It’s a long 40 minutes from “Kyrie eleison” to “Dona nobis pacem.” At least the journey was well conducted, in more than one sense of the word.