The Berkeley Symphony’s Dec. 8 program is a celebration of sorts: of a birthday and the premiere of a symphony, of the birth of a son, and of Bay Area composer Lou Harrison. To honor Harrison, Sarah Cahill, a noted Bay Area pianist, will perform his Piano Concerto.

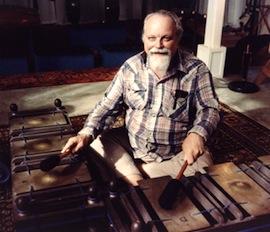

Harrison, for all his reticence about self-promotion, is a major figure both in Northern California and in contemporary American music, a groundbreaking pioneer of tonal and “world” music, and, in Cahill’s words, “a beloved composer in the Bay Area, thanks to the advocacy and stellar performances of musicians who worked with him.” She adds that “Harrison was among a group of ‘California composers’ who were more interested in melody than in complex harmony and were attracted to the music of Asia (geographically closer to California) than the music of Europe.” Although in the 1960s and ’70s his music was dismissed by many as simplistic, it’s music that Cahill describes as immediately appealing and full of gorgeous melodies. She also notes that today’s young composers are following in his footsteps, in terms of both influences and approach.

If you’re new to Harrison’s work, the Piano Concerto is a great place to start, as it incorporates many of the composer’s trademarks. Cahill explains it best: “First of all, it's scored interestingly for strings, three trombones, two harps, and a battery of percussion. It evokes the Indonesian gamelan to which Harrison devoted much of his life, but at the same time, Brahms is often evoked as an influence (one pianist calls it "Brahms-on-the-prairie"). The first movement is about thirteen minutes long, in almost traditional concerto/sonata form with an epic melodic sweep. Lou Harrison named the second movement "Stampede," which is, as he put it, "a large and rambunctious expansion of the medieval dance form Estampie. The third movement, a Largo, contains the only really chromatic music, reminding the listener that Harrison did have an interest in non-tonal and twelve-tone music (although neither are in this concerto). The last movement is only four minutes long, and here Harrison uses the North Indian style of Jalas.”

In addition, the second movement also showcases Harrison’s use of chord clusters (borrowed from Harrison’s teacher Henry Cowell), which comprise either all white keys or all black keys and are formed by using the forearm and hand. However, Cahill notes that in the second movement, “you need to maneuver passages of octave clusters very rapidly, which would be impossible to do with just your hand.” So, to create the sound, Cahill will be using a cluster bar. For those of us who have never seen one, a cluster bar is a wood block that’s covered with felt; it’s precisely the length of an octave. While she could have made her own, she has instead borrowed from the Lou Harrison archives at UC Santa Cruz, which seems fitting. (For a closer look, check out Cahill’s video on the Berkeley Symphony website.)

Even though this performance is a draw in itself, the rest of the program is equally interesting. It includes guest conductor Jayce Ogren conducting Sibelius’ Symphony No. 5 in E-flat Major (which premiered on the composer’s 50th birthday) and the West Coast premiere of Lei Liang’s Verge, which celebrates the birth of a son. No matter where your musical preferences lie, this will certainly a celebration worth attending.