After leaving Oakland’s Destiny Arts Center where she’d been for 30 years, Sarah Crowell got an exciting offer — curating Dance Mission Theater’s 2021 Dance In Revolt(ing) Times or D.I.R.T., a social political dance festival that debuted in 2015. Crowell loved her time at Destiny, where she is artistic director emeritus, but she finds it thrilling to take on projects like this and to work with her co-curator, Adia Tamar Whitaker, who she calls “ridiculously brilliant.”

“I felt like my eyes could look up in a way,” Crowell said. “I was never able to be in collaboration in this way.”

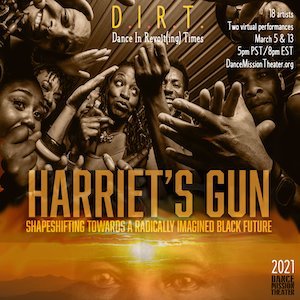

Crowell has been meeting online several times a week with Whitaker, the founder and artistic director of the performance ensemble Àṣẹ Dance Theatre Collective in Brooklyn working on Harriet’s Gun: Shapeshifting Towards a Radically Imagined Black Future. The festival comes around the time of the 30th anniversary of Los Angeles police officers beating Rodney King, and Crowell and Whitaker put together performances on March 5 and 13 with eight solo artists and eight dance companies from 12 cities. The curators say they had some ideas of what they wanted to create — and what they didn’t want. It was important to them not to do “pain porn that’s making money off of Black people’s suffering,” Whitaker said. Crowell agrees.

“Adia and I had these incredibly rich conversations about how we didn’t want to make this about Black pain but to imagine a Black future,” Crowell said.

Whitaker found this a bit of a new idea.

“I was trying to imagine a Black future, and I was disappointed in myself because I couldn’t really do it at first,” she said. “I realized, ‘You know why I don’t think about it?’ The future was never promised to my ancestors. But I’m the generation that can imagine a future. That’s dope.”

The name of the festival comes from the pistol Harriet Tubman was reported to carry with her when she took enslaved people to freedom — partly to encourage those she was guiding North who lost their nerve to keep going. For Whitaker and Crowell, the gun represents a radically imagined Black future.

“It was a guardrail. She used it to keep people on track,” Whitaker said. “It was a tool she didn’t ask permission to use, and I think of the dancers as the bullets in the gun.”

Crowell thinks Harriet’s Gun suits as a name for a festival about a commitment to change and that “transmutes historical and present-day trauma into sovereignty, grace, and forward motion.”

“It represents fierceness and insurance,” she said. “It was like, ‘This gun is going to your head, and you’re going to be free, or you’re going to die.”’

The idea of shape-shifting, expressed through the dancers’ movements, feels familiar now, Whitaker says.

“People are navigating the shared trauma of the pandemic and something new,” she said. “We’re over here shifting into the next thing, and we thought, ‘why don’t we just do what we do?’”

That simplicity is what Nkeiruka Oruche, the director of Afro Urban Society, said the ensemble wanted in their performance.

“We created a concert video exploring Black folks as the creators of things we love in the world, celebrating the beauty of our music, styles, dance, ease, and generosity,” she said. “It’s mostly spoken word and dance. It’s really simple and something that had to be shot outdoors with COVID-19 protocols, and it felt like it was back down to the basics — creativity and joy and humor.”

Getting to work with other dancers, even virtually, was a joy, Oruche says. “It’s beautiful to have the opportunity to get connected to different groups,” she said. “That’s the power of it. We’re not alone — we’re here, we’re surrounded, and we can keep connecting.”

Whitaker says offering work to the dancers in Harriet’s Gun was a pleasure.

“It’s hard times out here,” she said. “I’m happy to be able to pay people to keep it pushing and make new work. Artists are sensitive and it’s a low time.”

Two themes emerged in the two nights of performances, Whitaker says.

“The shows are so deep — they really carved themselves out,” she said. “That first show is all about air flight and the second one is all about water, and let’s go down to the bottom of the river and the ocean. It’s such a big part of folklore of the African diaspora.”

Crowell, who has performed and toured with many companies and taught dance, theater, and violence prevention for decades, believes that physical movement needs to be part of movements for social change. She tells a story about one of her students at Destiny, 16-year-old Shayla Avery, who organized several protests after police officers killed George Floyd in May. Crowell says before the pandemic her students had been working on a dance honoring young people in Oakland who were killed, which they were never able to perform, due to indoor performances being shut down. Crowell asked Avery if the students should come perform the dance at the protest, but Avery declined, fearing it would detract from the message. But a group of drummers came, and some people danced to their music, including Destiny dancers.

“She said, ‘I realized it was very important the dancers were there to move the energy,’” Crowell said. “She got it on a visceral level that dance is so important. People don’t change their minds about anything unless they feel it in their bodies.”