Even at the distance of 32 years, and of an abbreviated and somewhat flawed version, memories of present-day revival of Abel Gance's Napoleon persist. I remember well the 1980 San Francisco Opera House screening of the Francis Ford Coppola-sponsored road show of the four-hour version, with a score by his father Carmine, who conducted the orchestra.

But now, the San Francisco Silent Film Festival is going for the brass ring, in the most complete restoration possible of the 5 1/2-hour film, first shown in the Paris Opera in 1927. It will screen four times, March 24–April 1, in Oakland’s Paramount Theatre. The Oakland East Bay Symphony will be conducted by Carl Davis, whose score will be the live accompaniment to the film. This is the U.S. premiere for both the reconstruction and the music.

This is Kevin Brownlow's 2000 reconstruction, shown at the original 20 frames per second, with the final triptych. There will be three intermissions, including a dinner break.

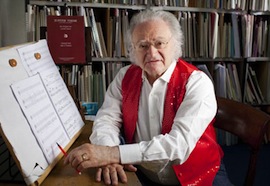

Photo by Davie Levene

The event will not be repeated anywhere else, and there are no plans to release this version on TV or DVD. So, this is it. For your marathon preparations: the film itself runs 5 1/2 hours, and with the addition of two intermissions plus a dinner break at 5 p.m., the performances starting at 1:30 p.m. will end at 9:45 p.m. ... or thereabouts.

Given Gance's Wagnerian ambitions, even this huge work covers only part of Napoleon's career, from boyhood to his first military expedition to Italy in 1797. Gance had planned a series of films to cover everything else, through the Egyptian expedition, the Consulate, the Napoleonic Code, Jewish emancipation, the Coalition wars, the Russian campaigns, Elba, and Saint Helena — but it was not to be.

Davis, 75, is one of the most prominent composers whose names are not well known. American-born English, he has written music for over a hundred television programs, and scores for movies such as The French Lieutenant’s Woman. IMDB lists 166 titles under his name. He has created accompaniment to the best-known silent films, including some of Charlie Chaplin's (those not scored by Chaplin himself), Ben-Hur, Wings, The Big Parade, and others. Davis' career began in the U.S., at Tanglewood, touring with the Robert Shaw Chorale and the New York City Opera; he started composing in his teens.

In the 1990s, he started collaborating with Paul McCartney, including The Liverpool Oratorio. He composed for numerous ballets, for Sadler’s Wells, then for choreographer David Bintley, for whom he composed Cyrano, and a new version of Aladdin.

Ned Sherrin invited him to compose for That Was The Week That Was; many other radio and television commissions followed.

Since 1997, Davis has conducted bi-annual performances of The Silents at the Royal Festival Hall with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, including Ben-Hur (1925), Flesh and the Devil (1927), The Student Prince in Old Heidelberg (1927) and The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921), and Intolerance (1916).

Davis says that, of all music genres he's been involved with, composing for film is his favorite:

The thing about film music is that it has to help the film. And you have to be able to recognize what kind of film it is. So you are on the side of the film, so to speaks. You see the film and you have to think what is the appropriate music to go with these pictures.It’s also what the whole film is about, because music has such a strong effect on the subconscious. It can actually suggest in itself a color and change people’s perception of the story or the effect the film is going to have.

If you have music, which is doing the wrong thing, it actually changes the actual nature of people’s perception of the film. So there is really a lot of emphasis, always was and still is, on how important music is for films. To get the right sort of music, I’m always searching for a solution. It has to be not only right for the picture as it comes, but also right for the whole film. It has to be right because most music appears generally — not always, but generally — at the beginning of a film, a TV program or a documentary. So that’s very important because that’s sometimes the first sound experience the audience is going to have. It must tell the right story.

In case of Napoleon, after that first impression, there are still hours and hours to go ...