Just after Halloween, the San Francisco Symphony will feature Yuja Wang, an audience favorite, appearing in a Chopin concerto. She will accompany the San Francisco Symphony on its upcoming tour of Asia, with performances in South Korea, Taiwan, China, and Japan.

But the concerts also open with a short, original composition by Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas, in a new revision for the Symphony’s imminent tour of Asia. Composed in 1998 and premiered on May 14 of that year in Davies Symphony Hall, Thomas’ Agnegram was written to celebrate the 90th birthday of Agnes Albert (1908-2002), an accomplished pianist who played Franck’s Symphonic Variations twice with the S.F. Symphony (under Molinari in 1932 and Monteux in 1952). “Through all the years of the Symphony, she was a steady and rallying force,” said Tilson Thomas. The 1998 score of the work may be viewed here:

As a young woman, Albert joined the Budapest and Pro Arte quartets for chamber music, and during the second half of the 20th century she was the San Francisco Symphony’s friend, mentor, patroness, and muse. In 1969, she gave $100,000 (matched by the NEA) to establish a music program in San Francisco Public Schools. Robin Freeman, director of public relations for the Symphony, writes, “She loved young people, and one of her enduring legacies is the SFS Youth Orchestra. Her generosity [$1million] made possible the Symphony’s Agnes Albert Youth Music Education Fund, Adventures in Music, and the Concerts for Kids and Music for Families series. In her later years, she helped ensure that Heifetz’s Guarnerius del Gesù violin, the ex-David, would be played in public after the great violinist willed it to the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.” She served on the Symphony’s board from 1952 until her death.

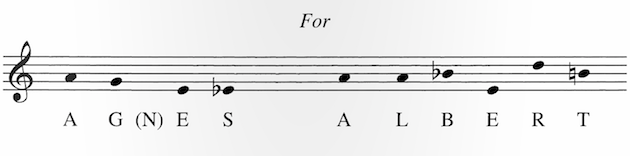

For the 1998 SFS program, Michael Tilson Thomas wrote that Agnegram “is a portrait of her sophisticated and indefatigably enthusiastic spirit. It is entirely composed of themes derived from the spelling of her name.” This excerpt of the piano parts reads:

AG[n]ES, AG[n]ES, ALBERT, A[or L]BERT

Cells derived from the opening motive A-G-E-S, include musical letters used by German speakers (S or “Es” representing E-flat and B representing B-flat). A few solfège syllables supply the missing letters (re for R, la for L, ti for T, the seventh degree of the C major scale, or B-natural) abound, and Thomas elaborates them into a basic “scale” of eight “unusually arranged” notes, from which all the themes are drawn.

On his recent revision of the flashy five-minute concert opener, Tilson Thomas writes, “Agnegram was originally written around the seven musical letters/notes that are a part of Agnes Albert's name,” and this septatonic [7-note] “scale contains a pentatonic scale—the most commonly used scale in Asian music. This prompted me to think about exploring more of those possibilities before we take the piece on our upcoming Asia Tour.”

The 1998 march for large orchestra begins with “a mini-concerto for orchestra” in 6/8, “giving brief sound-bite opportunities” for the motivic material to “settle into a jazzy and hyper-rangy tune.” The central trio section originally recalled “a kind of sly circus atmosphere” in which “different groups of instruments in different keys make their appearance in an aural procession.” After “the winds in C play a new march tune saying ‘Agnes Albert,' other instruments play the tune (spelled correctly) but sounding in their respective keys (not transposed): this created “a jungle-like cacophony ... punctuated by alternately elegant and goofball percussion entrances.”

Tilson Thomas’ update to the trio section, first heard in these performances, “explores a musical joke that I had planned, but not finished in time, for the premiere performance. The trio recalls many famous tunes that amused Agnes. There are surreal references to Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Verdi, and Irish lullabies, but they appear only to the degree that the notes that they have in common with her name will allow. I think she would have enjoyed discovering them and chuckling over them.”

The movement concludes with the jazzy 6/8 tune reappearing in canon and “the piece progresses to a jubilant and noisy ending.”