The Romero Guitar Quartet embodies a sense of history and the importance of lineage. On Saturday night, when the Omni Foundation and San Francisco Performances presented them in concert at SFJAZZ, their wizardry was on full display.

By the middle of the 20th Century, Celedonio Romero had studied with Joaquin Turina and established a successful performing career in Spain but the government of Francisco Franco did not allow him to give concerts abroad. Escaping from Spain, he settled in California and founded the Romero Guitar Quartet in 1960 with his three precocious and talented children, Celin, Pepe, and Angel. At the time the classical guitar was known only as a solo instrument but the Romero Quartet’s phenomenal success with audiences and fellow guitarists led to the establishment of the guitar quartet as a regular ensemble.

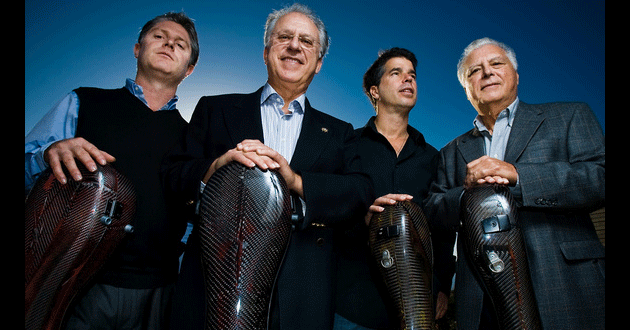

Inspired by the Romeros and their students in the Los Angeles Guitar Quartet there are now groups in every corner of the world from Dublin to Brazil and China. The Romero Quartet has evolved over the years and after the death of Celedonio and the dedication of Angel to his solo career, Celino and Lito, the sons of Celin and Angel, have joined original members Celin and Pepe to continue the family tradition of music making.

In concert the Romeros emphasize the flexibility of the format by presenting music for solo and duo performers as well as for the complete ensemble. The concert began with the quartet playing music from Celedonio’s youth, the colorful Prelude from La Revoltosa, a popular Spanish operetta full of national idioms, in an arrangement that took full advantage of the quartetʼs myriad colors.

The arrangement of the colorful Prelude from La Revoltosa, a popular Spanish operetta full of national idioms, took full advantage of the quartetʼs myriad colors.Pepe Romero, one of the most sought after recitalists in the world, played several solos of music written by his father and by Joaquin Turina. Celedonio Romero’s Los Maestros is a three movement work dedicated to his children and inspired by the flamenco form of peterneras which has been linked to the ancient Sephardic Jews and is full of gestures of suffering. Turina’s Fantasía Sevillana portrays the music performed each year in Seville during Holy Week before Easter. Pepe Romero’s incisive rasgueado (single finger strumming, typical of flamenco), brilliant arpeggios, and echoes of flamenco singers combined to create a vivid impression of a Spanish holiday.

Celino joined his uncle in a brilliant performance of Tonadilla a large-scale, three movement work by Joaquin Rodrigo. The opening Allegro, concise and brilliant, featured a brisk dialogue between the two guitars, punctuated by powerful strumming and Rodrigo’s characteristic added note harmony. The second movement, “Minueto Pomposa,” had a lyrical, occasionally mischievous outer section contrasting with an expressive song of exaltation underscored by bold rasgueado. Together, Pepe and Celino combined a telepathic ensemble with style, brio, and humor to create a memorable performance.

Together, Pepe and Celino combined a telepathic ensemble with style, brio, and humor.

Boccherini’s Introduction and Fandango, played by the quartet, begins with an aristocratic movement, delicate and Rococo in style. The Fandango, in marked contrast, is wild and exuberant, a courtship dance in three-quarter time featuring colorful harmony and rhythmic vitality. It is said to have been influenced by the playing of the great Spanish guitarist Padre Basilio, music master to the queen of Spain and later teacher of Dionisio Aguado. This was followed by two compositions by Manuel de Falla, the acknowledged master of 20th-century Spanish music. The “Miller’s Dance” and the “Danza Española No. 1” from La Vida Breve (The short life) are fiery flamenco dances, which the Romeros brought to life with constantly shifting textures, a wide-ranging use of color, and an almost clairvoyant fluctuation of tempo.

In a sentimental sequence, Celino Romero added a solo not listed on the program, “La Paloma,” a Cuban contradanza that he frequently played for his grandfather near the end of his life and then transitioned to one of Celedonio’s own compositions, the Fantasía Cubana.

Finally the quartet returned to the stage for La boda de LuisAlonso (The wedding of Luis Alonso) by Gerónimo Giménez, an exuberant tour de force drawn from a popular 20th-century operetta and arranged for guitar quartet by Federico Moreno Torroba and Pepe Romero. A standing ovation prompted several well received encores of even more Spanish music.