Presented by the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, whose William Kentridge: Five Themes exhibition is on view at MOMA through May 31, Kentridge’s Return of Ulysses was first performed in Belgium in 1998. From there, it moved to South Africa and other countries, where it reportedly became the stuff of legend. Now, thanks to a partnership between Pacific Operaworks and SFMOMA, the current revival — directed by Luc de Wit and featuring an all-American cast of singers and musicians directed by Stephen Stubbs — has migrated from Seattle to San Francisco.

The setting has also moved, from Ithaca and the Trojan War to a 20th-century hospital ward in Johannesburg. Amazingly, the dislocation is hardly disconcerting. Partly this is due to the unwavering respect paid to musical values, and to the intellectual intent and spiritual power of Monteverdi’s creation.

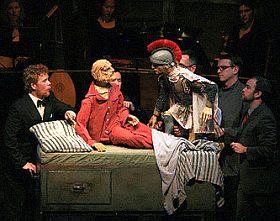

But the other reason for this production's success is that computer animation, singing, and puppetry of Basil Jones and Adrian Kohler’s Handspring Puppet Company of Cape Town, South Africa, all take place on and in front of an authentic-looking, two-tiered wooden platform on which the superb period instrumentalists — Stephen Stubbs (chitarrone), Maxine Eilander (harp), Margriet Tindemans (viola da gamba), Elizabeth Brown (archlute), David Morris (cello and lirone), and Ingrid Matthews and Alicia Yang (violins) — are prominently arranged.

No matter how modern aspects of this staging may look, there is no question that we are hearing as close an approximation to what audiences at the Venetian premiere heard as can be achieved through current-day research and performance practice.

The Dangers of Visual Overkill

If anything detracts from the production's ultimate impact, it is the busyness of Kentridge’s visual projections and computer animation. I am one of those people who feel that when an artist is singing an impossibly difficult aria, background shtick that can potentially diminish the ultimate impact of their achievement is to be avoided. (This may be less of an issue for younger music lovers, who have been raised in a milieu in which multitasking is, for better or worse, the norm).

There are times, especially at the start of the production — when black-and-white sonar, X-ray, MRI, and CAT scan images appear behind the allegorical human figures of Time (Tempo), Fortune (Fortuna), and Love (Amore), as well as an animated puppet figure of a dying Ulysses on a hospital gurney — that it's difficult to take in everything at once. But once you become adjusted to the juxtaposition, and find ways to move between singers, puppets, and projected supertitles while maintaining focus on the music, the wonder of it all makes for an emotional immersion rarely achieved by opera productions this novel. The visuals themselves are always compelling. Fully aware of the evocative potential of images, and ever respectful of the score, Kentridge knows when to touch with a flower, and when to stab with a sword. The one time he brings color into his projections — I’m not giving it away — brilliantly heightens the contrast of emotions that makes Monteverdi’s music so telling.

The Voices Meet the Music

Tenor Ross Hauck’s Ulysses cannot be praised highly enough. Hauck had a beautiful voice, and a countenance that captured both the ardent love and the suffering of the aged warrior. His portrayal was elevated, moreover, by an extraordinary range of subtle inflections. The singing was as nuanced as one would expect from a consummate art-song recitalist or bel canto specialist. Although he very occasionally pushed his voice beyond its comfort level, the stretch added to the emotional impact. I look forward to checking out Hauck’s contribution to the Naxos recording of Hans Krása’s Brundibár.

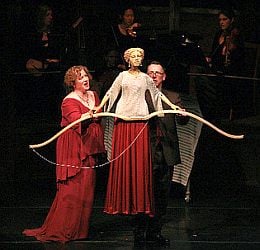

Canadian mezzo-soprano Laura Pudwell might not have shared Hauck’s great facility with inflection, but the beauty of her instrument and the profundity of her delivery made her Penelope very much an ideal partner for his Ulysses. Bass-baritone Douglas Williams (Time, Neptune) was the other standout, with vibrant vocal color on top and resonance at the bottom of the range. Look for his contribution to a future recording of Purcell's King Arthur from Les Talens Lyriques.

Although coloratura soprano Cyndia Sieden’s instrument is showing signs of age, she can still summon up pure tones befitting the roles of Love and Athena. Mezzo-soprano Sarah Mattox (Fate and Melanto) was equally lovely, as were the less often heard Jason McStoots, James. L Brown, and Zachary Wilder. These singers did a remarkably effective job of pairing themselves with the puppeteers, operating and moving in tandem with their alter egos.

If the box office pleads "all sold out," beg, borrow, or stand in line for last-minute cancellation tickets. This extraordinary production conveys a depth of beauty and love that resonate as strongly as they must have almost four centuries ago.