“The World of Henry Cowell” marks the second composer portrait series of Bard Music West, a Californian clone of Bard College’s annual music festival. Following the model of their inaugural 2017 season in honor of György Ligeti, artistic directors Allegra Chapman and Laura Gaynon carefully curated a program that traced Henry Cowell’s life and legacy. Three concerts at Noe Valley Ministry this past weekend featured choral and chamber performances of Cowell favorites and rarities, as well as works by his contemporaries, students, and spiritual successors.

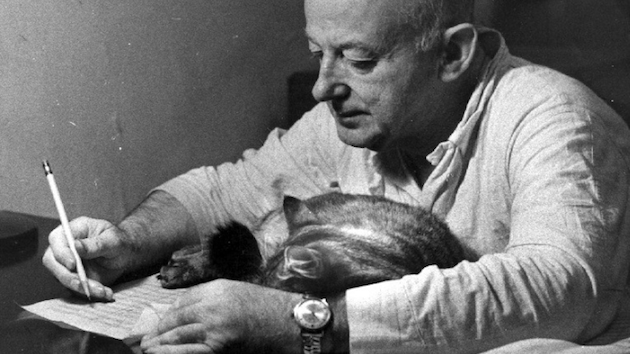

Born 1897 in Menlo Park — a century before Facebook, when it was still a sleepy little town — Cowell was a leading figure of an American strain of avant-garde music that emerged at the turn of the century. He’s best known known for his experimental piano techniques, both on the keyboard and inside the instrument’s “guts.”

Saturday evening’s concert included three solo-piano pieces played by Cowell biographer Joel Sachs. The hand and forearm clusters that punctuate Cowell’s chorale-like The Harp of Life (1924) widened into pummeling, double-armed masses for Tiger (c. 1928). In the former, Sachs managed to elicit rumbling bell tones with these dense chords; but the latter piece, inspired by William Blake’s poem, simply came across as a toddler’s temper tantrum.

I was terrified to see that Sachs was also to perform Cowell’s iconic The Banshee (1925) — in second grade, a sadistic music teacher fueled a week of nightmares after she played a recording for our class and described the howling ghost of Irish lore. Though the work has haunted me all these years, I was actually a tad disappointed when Sachs’s performance left me without the heebie-jeebies. Cowell instructs the pianist to stroke the instrument’s strings lengthwise with the flesh and nail of a finger to produce the hair-raising screeching effect that frightened me as a child. But Sachs couldn’t quite get this ghoulish wail to emerge; his rendition sounded more like a zipper.

There’s a slightly more refined use of extended string-piano techniques in George Crumb’s 1979 Apparition, a setting of excerpts from Whitman’s When Lilacs Last in Dooryard Bloom’d. Shockingly, Crumb claims that he wasn’t familiar with Cowell’s music when he wrote the piece, but there are other, earlier instances of composers exploring the interior of the piano independently of Cowell’s influence (among them, Harpo Marx in A Day at the Races). In the movement “Come Lovely and Soothing Death,” pianist Allegra Chapman tapped a cluster of low strings before hammering on the cast-iron frame of the piano with her fist. Her echoing knocks seemed to stand in for Death rapping at the door.

Soprano Sara LeMesh welcomed this grim reaper with a warm, gentle delivery of the opening line. Her shadowy dress and matching black lipstick made a striking, somewhat uncanny impression; in a particularly chilling moment, the soprano addressed the audience directly to sing Whitman’s text that death comes “to all, to each.” The movement closed with a second invocation to Death, this time with LeMesh allowing Crumb’s vocal line to droop slowly and delicately, like a browned leaf floating to the ground.

In addition to expanding the sonic and technical possibilities of the piano, Cowell played a crucial role in developing the Western percussion-ensemble repertoire—a genre that his friend and fellow “ultra-modernist” Edgard Varèse had pioneered with his 1931 Ionisation. Eight years later, Cowell composed Return for three percussionists while an inmate at San Quentin State Prison, where he was serving time for engaging in homosexual acts. Ben Paysen, Sam Rich, and Tim Padgett offered an aggressive reading of the score, reveling in the clanging gong crashes and warlike tom-tom tattoos.

Cowell originally intended for dancers rather than trained musicians to play Return, and while there was very little choreography from the trio of percussionists (aside from the usual head-bobbing), the work did end with a mystifying theatrical gesture. After a climactic gong blast, Padgett emitted a siren-like yelp, to which Paysen responded with a tiny tinkle on bell chimes and a soft breath of air on glass chimes. It evoked a strange, ritualistic atmosphere, as if some shrieking demon had been exorcised.

The presence of East Asian instruments like the tam-tam, temple blocks, and Japanese cup gongs in Return is indicative of Cowell’s reverence for non-Western musics. He was one of the first American composers to seriously engage with the musical traditions of other cultures, sharing his knowledge at Stanford in the 1930s with a summer course titled “Music Systems of the World.”

Homage to Iran from 1957, a souvenir of Cowell’s sojourn in the Middle East, moves beyond the exoticizing Romantic tendency to represent the orientalist “Other” with a simple harmonic minor scale. Cowell fully embraced the modes, rhythms, and techniques of Persian classical music, expertly translating these elements into a Western idiom. The solo part for violinist Luosha Fang (who gave a spirited performance of Carlos Chávez’ feisty little Sonatina earlier in the Saturday afternoon program) stood in for the Iranian bowed kamancheh. You might have guessed that Fang was brought up in this style—she played Cowell’s swirling melismas so naturally and with such subtlety that I was convinced she had improvised the whole piece. Meanwhile, Iranian-born Shahab Paranj was, in fact, improvising much of his accompaniment on the goblet-shaped tombak drum; he has a virtuosic command of the instrument, manipulating the skin at one point to produce ascending and descending lines that paralleled the melody.

Cowell also looked to various Western vernacular traditions, inspired by the field recordings of his Berkeley composition teacher Charles Seeger (father of Pete Seeger). United Quartet from 1936 shows the influence of Jewish and Eastern European folk music on Cowell’s eclectic compositional language. The Telegraph Quartet, currently an ensemble-in-residence at San Francisco Conservatory, athletically attacked the Rite of Spring-style off-beats in the opening 5/4 Allegro. The movement is heavily indebted to Bartók, who, in turn, admired the music of Cowell, asking permission to borrow his “trademark” tone clusters. In the Andante that followed, violinist Jeremiah Shaw gave a gorgeous interpretation of the Hebraic-sounding solo, gracing the melancholic melody with just the right amount of portamento.

Arguably, Cowell’s greatest contribution to modern American music was his generous advocacy for young and neglected artists, notably his friend Charles Ives (whose Piano Trio was featured on the Friday-night concert, which I didn’t attend). Bard West took up Cowell’s example by showcasing the works for two living composers.

In honor of Cowell’s collaboration with Martha Graham, the festival’s 2018 composer-in-residence Eugene Birman teamed up with choreographer James Sofranko of SFDanceworks on The Sound of Your Solitude and Mine. Birman’s score for the New York-based “Pierrot ensemble” Third Sound had some sensual moments, especially the nocturnesque solo for flautist Sooyun Kim, whose husky tone and flirtatious pitch bends were accompanied by her colleagues’ cricket-like whistling. But elsewhere, the work felt like a disorganized barrage of noises—honking clarinet, squealing strings, and Kim’s tea-kettle peeping on piccolo, which was physically painful to hear. Contemporary composers have reached a decadent phase in their overuse of these kinds of extended techniques, which work best as “ornaments” in service of more idiomatic playing (as Cowell elegantly demonstrated in his own music).

Sofranko’s choreography for Brett Conway and Danielle Rowe drew on classical ballet, with an emphasis on long, outstretched limbs. The dancers seemed to embody some pair of struggling lovers, holding one another up as they faltered. Their movements sometimes felt overdramatic, like the exaggerated poses of a silent-film actor. Unfortunately, I was unable to see much of the choreography, despite being seated in the third row. While Noe Valley Ministry is a stunning space for chamber music, its flat, unraked floor and thick, wooden columns guarantee that most sightlines will be obstructed. The festival organizers might consider a more visible setup in the future.

Third Sound’s performance of Wang Lu’s Urban Inventory (2015) fared much better. Cowell, who grew up hearing immigrants sing Cantonese opera, would have appreciated Wang’s incorporation of music from her native China. The work presents a soundscape of city life in Xi’an, weaving together street recordings with instrumental material. In “City Park,” woodwind air tones representing abating smog gave way to evocations of buskers and playing children.

There’s a whimsical, freewheeling character to Wang’s music; for “Once upon a time, in another lifetime,” pianist Orion Weiss tossed off sparkling, Flight of the Bumblebee-style runs as violinist Karen Kim and cellist Michael Nicolas executed ascending glissandi that seemed to evaporate into the stratosphere. The title of this second movement suggests that Urban Inventory is a nostalgic collage of Wang’s childhood; now an assistant professor at Brown, Wang was born in Xi’an to a family of folk musicians. Snatches of pentatonic melodies from the live players and recordings of traditional Chinese ensembles surfaced and dissipated, as if they were Wang’s musical memories of her youth.

A fascinating feature of the piece was the ensemble’s imitation of Chinese speech patterns in the aptly titled “Gift of Gab” movement. As a tonal language, Mandarin lends itself to this kind of musical translation. Conductor Patrick Castillo kept the tempo loose and lilting, allowing the players to convincingly convey the flexible rhythms of spoken Chinese. At the end of the work, however, Castillo pushed the ensemble toward an overpowering final chord that called to mind those radiant cadences that end many of Messiaen’s works. Seconds after the cutoff, I had ordered Third Sound’s recording of Urban Inventory from Amazon—it was one of the finest works of new music I’ve heard in a while, and the highlight of a successful sophomore festival from Bard Music West.