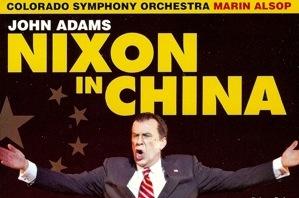

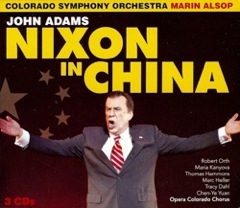

Those of us fortunate enough to attend Opera Colorado’s 2008 production of John Adams’ engrossing opera Nixon in China were swept to our feet by its cumulative impact. Given that the performance of soloists and Colorado Symphony Orchestra, under the able hand of Marin Alsop, and the Opera Colorado Chorus under Douglas Kinney Frost, was witnessed by many hundreds of the music and arts critics and personnel who had descended on Denver for the 2008 National Performing Arts Convention, the artistic triumph was all the greater.

The opera, a true collaboration between Adams and librettist Alice Goodman, focuses on the seven days in early 1972 that red-baiting President Richard M. Nixon (sung by Robert Orth), his dutiful wife, Pat (Maria Kanyova), and Secretary of State Henry Kissinger (Thomas Hammons, reprising the role he sang at the 1987 premiere) spent in China with Chinese revolutionary leader Chairman Mao Tse-tung (Marc Heller), his authoritarian wife and Cultural Revolution architect Madame Mao (Tracy Dahl), and Premier Chou En-lai (Chen-Ye Yuan). If the visit failed to produce any major diplomatic breakthroughs, it nonetheless gave Adams and Goodman full opportunity to exercise their genius.

Adapting minimalist repetition to higher ends, Adams’ music in its mechanical aspects underscores the machinelike state militarism and diplomatic posturing of both countries’ leaders. Under those intentionally ceaseless and anything-but-tedious musical mechanics lies another layer, the personal. Here, Adams and Goodman use words, innuendo, and subtle changes in musical texture to reveal the humans behind their political masks.

Listen to the Music

Act 1, Scene 1: Beginning

In Act 1, Scene 1, Orth as Nixon intentionally adopts an almost hectoring, stentorian tone to sing, “News, news, news, news, news, news, news, news, news, news has a has a has a has a kind of mystery, has a has a has a kind of mystery — y-y-y-y-y ...” His shallow posturing plays to the TV cameras, and ignores Chou En-lai’s near-futile attempt to introduce him to Madame Mao. As the unstoppable orchestral repetition makes inescapable the political script that Nixon is playing out for all the world to see, the libretto questions the depth of his commitment.

In Act 2, the real personalities come to the fore. As Pat Nixon tours a Chinese glass factory, health center, pig farm, and primary school, her arias reveal her values, vulnerability, and limits. (Her husband’s own are obvious from the start.) The Chinese don’t fare much better, as the ballet, called The Red Detachment of Women, reveals the darker underpinnings of the revolution. As for Kissinger, the lech beneath the cartoonish mask serves as the ultimate object of revulsion.

Although the Nonesuch original cast recording, conducted by Edo de Waart, features SFCV’s own Stephanie Friedman as the Second Secretary to Mao, it’s important to note that it was recorded in either 1987 or 1988 (sources differ). Its early digital sound cannot compare to what current digital recording technique can offer. That makes the new recording indispensible. And the music, which benefits from the extra color digital advances bring, is fabulous.