A body, bamboo, brushes, and barenaked voices were at the forefront at “Full: Breath,” the Berkeley Art Museum and Pacific Film Archives’ October 15 full-moon celebration. Technology may sometimes prevail at the Full series of varied performances held on the night of each month’s full moon, but for a variety of reasons on this exceptional evening of rare rain and solo, duet, and small ensemble art, low-tech was elevated in every instance above electronics.

Originally curated by Berkeley pianist Sarah Cahill, Full features mostly Bay Area artists engaged in experimental dance, music, theater, spoken word, and visual art activities. Entering the fall season of its first year of programs, Full is curated by a rolling roster of local artists and organizers. Breath was programmed by Shinichi Iova-Koga, artistic director of San Francisco-based physical theater and dance company, inkBoat, and included shakuhachi master Masayuki Koga, dancer Dana Iova-Koga, vocal duo Ghost Lore (Tim Kim and Katherine McDonald), and live calligraphy painting by Aoi Yamaguchi.

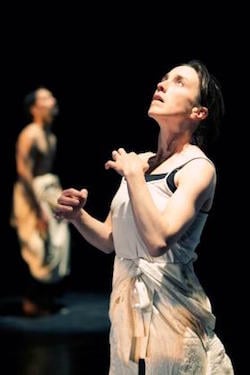

Dancer Iova-Koga’s untitled solo was by far the night’s most captivating performance. Her lithe, travel-through-evolution dance managed to be gripping, humorous, heartbreaking, and searingly honest. McDonald’s vocal accompaniment provided a subtle partner.

Beginning on the floor — frustrating some people because the large audience tucked into the museum’s back atrium reduced sight lines — Iova-Koga extended her left leg. Her bare foot, crooked and displaying wrinkles and soft gray dirt picked up from the floor, quivered with vulnerability. Or maybe it was simply a primordial experience of breath passing through a body that moments later swam, surfaced, briefly squatted, and sauntered like a gorilla before gaining verticality. With a blink and deliberate, two-second stare-downs, Iova-Koga established that a human being had arrived.

Astounding in it’s subtlety and with each progression achieved in mere seconds, the solo progressed through a panoply of human history: self-awareness, celebrity, athleticism, gun violence, lust, industrialization, objectification, gender identity, automation, and on and on. Her gestures suggested society’s full spectrum — a friendly wave to people outside the museum who paused to look through the windows and elicited delighted laughs from the audience; a “forgotten” left arm extended to one side as if encircling the shoulders of a companion while the right arm competed for attention by flagellating and engaging in a busy, repetitious, dehumanizing chore; an invisible cell phone held in one hand that moved to her face and became a blindfold and an allegorical gesture whose meaning was clear in our era of preoccupation with mobile devices.

If it sounds cliché-ridden, it was not. Impeccable timing and a choreographic arc that made each point but never overstayed the moment made evocative, organic statements. The end, with a return to the floor, left Iova-Koga lying on her side, back to audience, ribs expanding and contracting as she breathed, her upraised thumb and pointer finger separated by centimeters in a “pincher” position as if to suggest that this small space, this gap, is where our last breath remains just before life ends. It was a remarkable performance.

Impressive also was Masayuki Koga, displaying control and power in three songs he performed on the Japanese flute. The shakuhachi’s rich tone makes it a pleasing instrument to listen to. In the hands of a skilled professional, warm color blended with raw texture to extend its range. In “Ancient Wind,” Koga built an improvisational piece from non-Western and non-Japanese scales that he said were “emotional scales.” Breath was three-dimensional: heard at his mouth, within the flute, and in the notes filling the atrium.

Yamaguchi’s 23-minute calligraphy performance devoted much of the time to slow-paced set-ups with assistants unfurling or manipulating large-scale canvases. Perhaps because it was last in a program that lacked concise transitions between performers — or due to an admittedly Western mindset that by this time was resistant to slow motion — dramatic intent was lost. When Yamaguchi finally sprang forward, her broom-length brush blackened with pigment, expectations were high but the results, despite the beauty, left too many unresolved questions. Who was leading, the paint or Yamaguchi? Did she see the image before it was created, or respond to what occurred, or both? Having questions following the viewing of a work isn’t necessarily negative, but not having a sense of a work’s essence as it ends is a hollow feeling.

Ghost Lore’s Kim and McDonald suffered through insurmountable technical problems during the first two of five songs. A decision to “ditch technology” and set aside handheld mics that screeched painfully and unpredictably was the evening’s best move. Together, their voices offered a wonderful harmonic blend: McDonald’s sound was buoyant, with bell-like clarity and balanced by Kim’s deeper color and textural nuance. Well-written lyrics drawn from varied origins that included mundane conversation, rhymed poetry, newspaper headlines, talk radio, and others, made the songs thought-provoking. Without knowing the full impact that failed technology had on Ghost Lore’s music, it was hard to draw conclusions. But the evening as a whole provided one: Traveling through the human body or expressed by voice, resonating in a bamboo flute or lofting the bristles of a paint-filled brush, breath was not only fragile and precious, it was a mighty force.

The Full series continues with:

Full: Stay on Monday, November 14, 7 p.m.

Full: Adapt on Tuesday, December 13, 7 p.m.