Starting off with an Etude for the left hand alone is not the typical way to begin an orchestral concert. It was, however, the perfect musical gesture for Berkeley Symphony and Conductor Joana Carneiro to celebrate their third season together on Thursday everning. And you only had to stick around to hear and, in effect, believe in the miracles that youthful talent and vitality can produce when combined with courage and imagination.

The Berkeley Symphony has long been dedicated to the work of younger composers. Gabriela Lena Frank’s Vandaval (Cyclone), was written as a memorial to a longtime symphony supporter, Harry Weininger. It was given a fiery and thoughtful performance by the composer and set the tone for the serious reflections as well as the virtuoso fireworks that were to follow.

Its central section is a single line for left hand alone, in perpetual motion whose tireless, whirling rhythms are enclosed by elegiac chords for both hands. It was at once an Etude (and showpiece) but it was also a dramatic way of paying tribute to the efforts of individuals working behind the scenes that sustain large performing groups.

A short work for chamber orchestra and electronic sounds, Enrico Chapela’s Li Po (2009) is based on a Mexican poem by Jose Juan Tablada, Drinking Alone with the Moon, about the Chinese poet, whose work was used a century earlier as the text of Mahler’s Song of the Earth. Chapela’s work reverses the roles of words and music, transforming the text electronically into an unearthly growl that seemed to stagger and moan amidst tipsy string glissandos, which may have come from a synthesizer. A manic marimba solo, dazzlingly played by Ward Spangler, seemed to personify the lone drinker off on a binge. Carneiro balanced these sounds deftly, immersing the audience in a unique musical experience.

The Third Symphony of Brahms concluded the first half of the concert. From the start, Carneiro was in her element, urging even the downbeats the orchestra heavenward. Using her entire body, she elicited a sound that was full of warmth while fully expressing the Brahmsian Sturm und Drang. Yet behind the passion lay a reading of surprising depth and subtlety as well.

The lilting dance of the second movement sang contentedly with its feet solidly on the earth until the soaring theme at its close lifted us back into the world of the first movement. In the third movement Carneiro found a tempo that enabled the horn solo played by Stuart Gronningen to move ahead, and yet linger at the top of phrases with heartbreaking restraint.

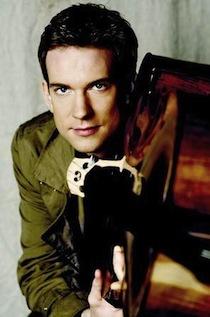

There wasn’t much lingering in the Shostakovich Cello Concerto (1959) played by the young German-Canadian cellist Johannes Moser in his Berkeley debut. Written for the great Russian cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, it is a work that revels in seemingly limitless technical capabilities of its soloist.

Moser was more than equal to the technical challenges of the concerto and he entered the spiritual world of Shostakovich to an astonishing degree. His performance of the second movement invoked the dungeon scene in Beethoven’s Fidelio (read: Stalinist repression). While the cello (the prisoner) plays quiet double stops in harmonics we hear an angelic voice as from a great distance played with otherworldly delicacy on the celesta by Miles Graber. This conversation lasted but a few moments, yet time seemed to stand still.

In the following soliloquy the intensity built to an almost unbearable degree. It was as if you forgot you were listening to the cello, but rather to an actor speaking into the void, punctuated by pizzicato chords articulating the silence. The finale was played with blazing intensity, like a liberation (or an immolation). It was certainly a victory for composer, performers, and audience.