Photos by Peter da Silva

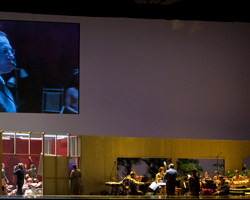

As the intentionally sketchy plot of this oft raucous, two-act musical memoir unfolds, four single and three multipurpose characters weave in, out, and in front of two rooms at the left of the stage and the large space for musicians in the center and right.

At the same time, Balinese dancers gesticulate; “subtitles” of the hard-to-understand English libretto project on a long, narrow screen, awkwardly positioned right below the stage apron, and two videographers weave in and out while projecting images that often include each other on a large screen that dominates upper stage left.

An antiquated TV that could not have existed in the 1930s, when the opera is ostensibly set, projects black and white images in the bedrooms of the house, while six members of the Bang on a Can All-Stars, including guest violinist Todd Reynolds, do at least some of what their name implies, and the 18-member Gamelan Salukat engages in irresistible percussive cacophony. Sometimes the empty, rumpled, bed is covered by young, bare-to-the-waist Balinese musicians who collapse on it more than once in the course of the opera.

In sum, the opera provides a window on the sensual assault of Balinese culture that compelled Canadian composer Colin McPhee (whose 1946 memoir provides the basis for the libretto) to live in Bali and literally fixate on his experience there.

Disordered Sense-Impressions

of composer McPhee

The work makes an impact as much for its intentionally jumbled, all-encompassing gestalt as for its purely musical aspects. There’s so much going on, and so much stream of consciousness dialogue, that only by reading both the synopsis and Ziporyn’s two-and-a-half page program note can you learn that the libretto includes pivotal events that are sometime depicted only by obscure symbolism.

Most characters are hardly fleshed out. In particular, Margaret Mead, whose 1942 book, Balinese Character, was another source for the opera, seems almost cartoonish in her detached sociological pronouncements that dominate the Epilogue. She was marvelously sung by the fearless, world-class soprano Anne Harley.

McPhee himself, sung by the clarion voiced, haute-contre (high) tenor Marc Molomot, emerges as a driven, blank-faced obsessive who has sex with underage Balinese men in the back of his mind. Note that his wife, who accompanied him on his trips, is never mentioned. The actual McPhee, who returned from Bali, divorced his wife, and later roomed with both Bernstein and Britten, died of depression and alcoholism in 1964.

The third Westerner in the opera, painter Walter Spies, who is freely portrayed by the slim, towering tenor Timur Bekbosunov, seems as nonplussed as Molomot is gripped. As depicted and hinted at in the opera, the real-life Spies was flitting, flirting, and no doubt screwing away until the Dutch authorities arrested him in an antihomosexual purge shortly after McPhee left Bali in 1938. (Although Mead helped secure Spies’ release nine months later, he died in 1942 when a Japanese bomb hit the ship that was deporting him and other German nationals from the Dutch East Indies.)

The main Balinese character, who does not sing, is Sampih, whom McPhee brings into his house after the young boy saves him from drowning. Untamable at first, he gives hints at the opera’s end of the newly emerging dancing prowess that eventually landed the historical Sampih a lead role in John Coast’s Dancers of Bali. (He was brutally murdered at age 28.) Thirteen-year old Nyoman Triyana Usadhi was marvelous in the role. Equally so were the three Balinese dancers: Usadhi’s father was I Nyoman Catra, a master of traditional Balinese masked dance who specializes in clown roles; riveting dancer/choreographer Kadek Dewi Aryani; and dancer/choreographer Desak Madé Suarti Laksmi.

One problem with comprehension was the sound design. In an opera in which everything, including the impossible-not-to-hear gamelan, was amplified, sound director Andrew Cotton had Molomot’s headset mike turned up higher than everyone else’s. The high tenor’s voice tended to distort in his loudest passages. Throw in two other singers plus all the musicians, and you had sections where the din was painful. Perhaps no one told Cotton that the location of the soundboard, under the mezzanine overhang in Zellerbach’s dry acoustic, greatly skews sonic perspective.

A House in Bali is very much a stream of consciousness immersion in the clash and clatter of cross-cultural convergence. Whether you consider it a swim in the dark, or a gripping descent into the deep recesses of the unsettling subconscious, depends in large part on your comfort with the unknown. Personally, I found many of the images and astounding sounds haunting me the morning after the experience. Nothing short of seeing it live or on DVD/Blu-ray can possibly convey its visceral impact and unsettling beauty.