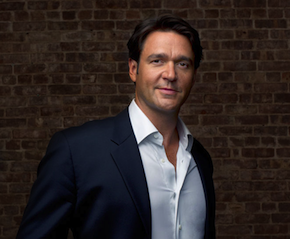

The prominent baritone Nathan Gunn came to Berkeley on March 9, with a spacious and generously programmed evening that focused on German lieder in the first half (Schubert and Schumann) and turned to songs with English lyrics in the second (Barber, Ives and Bolcom). The singer’s wife, Julie Gunn, accompanied him for the performance, presented by Cal Performances. Both offered some friendly commentary along the way, enhancing the connection between artist and audience at the First Congregational Church.

What figured to be a choice evening fell considerably short of expectations. While the Gunn team delivered potent numbers and moments along the way, like sudden eruptive flashes, the inner light of the music was often obscured. This was not a night for the sort of interpretive nuances and poetry set aloft that many fans of art songs savor.

Nathan Gunn possesses an impressive, deep-grained voice. He generates a big, full sound, with blast-furnace fortissimos, lush but tactfully applied vibrato and a flair for rhythmic surprise. But making a song come alive for a listener requires a sense of both musical and dramatic engagement with the material. Gunn’s often routine readings of the texts and oddly stiff demeanor left much to be desired. That was especially surprising for an artist whose abundant stage credits include leading roles at opera houses around the world, concert-version Broadway shows (most recently a Carnegie Hall Carousel) and a cabaret act. He’ll be back at San Francisco Opera this summer, in Mark Adamo’s The Gospel of Mary Magdalene.

The other, essential component that came up lacking was the sensitive interplay of voice and piano. Julie Gunn’s keyboard work favored volume and showy effects over a shapely and responsive temperament. Church acoustics can be tricky. It may be that she was having trouble hearing herself and her husband as clearly as she might have. But it was hard not to recall the recent dialogue between another celebrated baritone, Thomas Hampson, and his pianist, Wolfram Rieger, at the Herbst Theatre. A good-sized gap lay between that kind of transporting musical communication and this often earthbound exchange. Even the Gunn program book stumbled, by omitting a page of texts and translations.

The program began with five Schubert songs. The two most vigorous selections, Im Walde and Auf der Bruck, worked best. The propulsive, clattery evocation of a horse charging through “forest stretches deep and dense” in the latter was especially fine, with Gunn galloping into a near-shout at one point. But when it came to the finely etched Nachtviolen (“Dame’s Violet”) the requisite delicacy was missing.

Schumann’s wonderful Dichterliebe came next, offering a chance to paint on a wider canvas. The poignant opening number, Im wunderschönen Monat Mai, bloomed open with a Spring-like ardor. The Gunns mounted a vivid sonic edifice of the Cologne cathedral in the sixth song of the cycle. A dream song took on a confiding cast later on, like something whispered across a pillow.

Such felicities made the half-filled opportunities elsewhere stand out. Gunn made a tender profession of love in Wenn ich in deine Augen seh’, but the tincture of bitterness at the end melted away. The heartbreak in Ich grolle nicht was more like a glancing blow. When the singer rose to the occasion in the glowing Am leuchtender Sommermorgen, the piano stepped on his well-formed lines.

The second half of the program came off somewhat better. Barber’s With Rue My Heart is Laden was both elegant and touching. In that composer’s concussive I Hear an Army, the Gunns had another chance to let loose the horses, and took full advantage of it, rising to one of the more dramatic crests of the night.

The singer showed some acting chops and humor in Ives’ The Circus Band and turned the subsequent “Down East” into a sepia-tinged nostalgic miniature. Bolcom’s broader numbers, whether sinister or satiric, offered still more room for Gunn to roam. He spoke a few lines, lofted a cross-dressing falsetto and narrowed his eyes at the menacing Black Max. But his heart never seemed fully in this sampler of American humor. The audience’s laughter felt perfunctory.

Gunn was far more present in the single encore, Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? Often treated as kind of moody period piece, Yip Harburg and Jay Gorney’s 1931 song is an angry cry of social protest. Gunn got every ounce of the rage. It made a startling closer to an evening that remained, for too much of the way, in a murky middle ground.