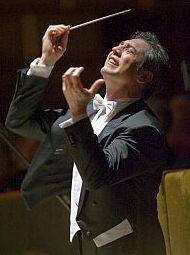

Luisotti seemed to identify most with the program opener, Kodály's Dances of Galánta. Conducting with arms, shoulders, head, and chest as well as head, sometimes bending side to side from the waist with an energized flexibility that would cause heads to turn on a dance floor, the maestro seemed as swept up in the spirit of Hungarian gypsy dance as he was moved by Kodály’s heartfelt settings of traditional themes.

For perhaps the only time in the evening, the orchestra followed suit. The violins' first entrance was filled with feeling, and Carey Bell’s clarinet solo bubbled over with warmth. Everyone seemed to be pouring their considerable all into this colorful work. The performance was a joy.

If only as much could be said about the rendition of Bloch's Schelomo-Rhapsodie Hébraïque. Bloch originally conceived the work as a vocal setting of Solomon’s words in Ecclesiastes 1:2-9: "Vanity of vanities; all is vanity ... One generation passeth away and another generation cometh, and the Earth abideth forever." But he temporarily abandoned the project in 1914 when he felt that none of the languages he was fluent in could adequately express his feelings. He resumed writing after he met cellist Alexander Barjansky, and was moved to adopt his music for the "infinitely grander and more profound voice" of the cello.

For whatever reasons, SFS principal cellist Michael Grebanier seemed mostly content to skim the surface of Bloch’s Song of Solomon. Rather than inflecting passages as a Jewish cantor would, Grebanier approached his notes straight, with nary a trace of angst or inner warmth. The tone was wan, and at times buzzy. Luisotti came to life in the few passages where the orchestra was able to break loose without concern for overwhelming its soloist comrade — most of the time, Grebanier’s soulless playing dominated the proceedings.

Bordering on Brahms

If any music calls for soul and warmth, it is the fourth and final symphony of Johannes Brahms. The performance started strong, with gorgeous strings and an expressive sigh that was passed from section to section. Before long, however, the balance between strings and other sections went temporarily awry. Some passages overflowed with beauty, while others were sabotaged as musical commentary inappropriately subsumed the melody line. Whether Luisotti had enough time to step back and hear the grand picture, as in a sense you do when conducting orchestra and singers from the pit, I do not know. But he certainly seemed to lack the ability to unify the orchestra into a coherent entity.

Although the second movement allowed us to hear the tenderness and longing beneath Brahms' opening cries of angst and despair, it failed to reach deep enough into his soul. Despite some gorgeous soaring passages, and great beauty in the sweeps of the cellos, there were too many "almost" passages, too many lullabies and heartfelt sighs longing to come out. Perhaps if Luisotti had lingered more, or given the orchestra greater permission to sing their hearts out, the emotions that he clearly sensed in Brahms' writing would have penetrated to the core.

After a third movement that was not as stirring as it could have been — there's a reason Brahms wrote music that could have easily served as a rousing finale, yet chose to follow it with music far more tragic — Luisotti encountered more problems with balance. There’s an extended section approximately five minutes into the fourth movement when the strings repeatedly emit a downward sigh each time the winds speak. No matter how the winds try to move forward, the strings sigh and pull them down. Finally the winds peter out and surrender, leading the entire orchestra to cry out in despair. Rather than varying the volume and expressivity of those telling sighs, Luisotti rendered them uniform and monotonous.

To his credit, Luisotti consistently illuminated the reasons why Brahms orchestrated as he did. He pointed the way, which is far more than many conductors do their first time before an orchestra. As for fully seizing the music and sinking so deeply into it that only the heart could be heard, that was left for future performances.