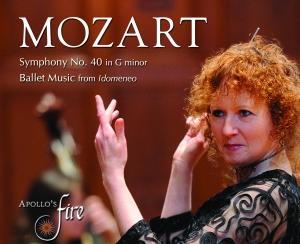

It’s a tried-and-true strategy for constructing programs, concerts, and CDs alike: Make certain there’s a surefire favorite in there somewhere, then pack around it as much unfamiliar music as you dare. Not often, though, have I seen it deployed as baldly as it is on the new Mozart recording by the Cleveland-based period-instrument orchestra Apollo’s Fire.

First on the disc: Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 (the “big” G-minor symphony). Afterward: Mozart that most concertgoers will never have heard — a recitative and aria from the early opera Lucio Silla, the ballet music from Idomeneo, and a clutch of (mostly) contredanses. If the symphony serves as a lure to attract listeners to the other half of the disc, it will have done well. Everything here is Mozart — and Mozart-playing — of high quality.

That said, I found the symphony performance marginally less interesting than the others. Apollo’s Fire director, Jeannette Sorrell, is an intelligent, thoughtful Mozartean (as her exceptionally interesting liner notes attest). Nonetheless, she seems to me to slight the fierceness and the strangeness of this, Mozart’s most pathos-laden symphony.

Listen to the Music

Mozart Lucio Silla - Parto, m'affretto

You notice it clearly in the dynamic range. Few large contrasts are evident, and at no point does the orchestra ever seem to be playing at full strength, in the sense that there’s any feeling of strain in the sound. Small “period” orchestras often sound bigger than large “modern” ones in late-18th-century music, merely because they can — and do — play at their dynamic limits, where a “modern” band wouldn’t dare. But here the 20 string players sound no bigger than their numbers. Nor do they articulate very sharply; the vibrant “chiff” on the front edge of a note that can lend a thrill to forte passages even when the number of players is small doesn’t have a large place in their arsenal.

Where they excel is in shaping of phrases, silkiness of tone, and weighting of beats. It’s supremely elegant playing, matched and even bested by that of the suave wind band. It seems a lifetime ago that the complaint about “period” winds was that they were raucous, shrill, and ill-tuned. If anything, Sorrell’s immaculately tuned winds and brass are too delicate, too recessed. With so small a string band, they ought to dominate the texture more than they do.

The rest of the disc is a different story. Sorrell’s band takes to the dance music here like a pack of hounds catching a scent. There’s an eagerness and an attention to small-scale gesture that I didn’t hear in the symphony. There’s bite, too: In the disc’s final contredanse, the orchestra sounds like it is, at last, playing to its capacity. The Idomeneo music is marvelous — bright, winsome, terrifying, and brilliant by turns, with the Apollo’s Fire strings demonstrating in the last number that they can so dazzle.

They saved the best for, well, second. After the symphony and before the dance sets comes “In un istante … Parto, m’affretto” from Lucio Silla. Hearing it (for the first time) made me wonder why singers don’t more often plumb the earlier Mozart operas for material. High sopranos are, finally, singing some of the more impossible Mozart concert arias. (The Queen of the Night aria, from The Magic Flute, with its F above high C, was not a one-off; Mozart wrote a lot of music even more taxing.) I haven’t seen many of them, though, poking around in the earlier operas.

This aria isn’t particularly high — I think it tops out at D — but it demands fantastic dexterity and accuracy. And soprano Amanda Forsythe nails everything, with such insouciant ease that you might almost think she was daring the audience to think her capable of misstepping. And with no strain at all — no squalling, no squeezing, and hardly any constraint.

It’s true that a listener with no Italian, and no translation, might not guess that the aria is about anguish and death. To make that music mesh with that text means making an ugly sound. But Mozart himself makes that difficult; it’s all fantastic fun, musical play, and why shouldn’t anyone play the game as well as possible?