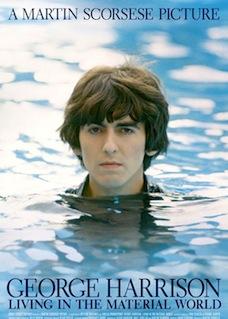

George Harrison: The quiet Beatle. The spiritual traveler. The celebrity who, despite generous communication of his innermost private thoughts, remained something of an enigmatic figure until his very end. These are the impressions of Harrison that viewers are likely to take away from Martin Scorsese’s new HBO documentary, George Harrison: Living in the Material World.

The two-part, three-hour biographical film memorializes Harrison’s adult life. His teenage introduction to John Lennon and Paul McCartney serves as the earliest chronological point in the film. The documentary’s first installment covers most of the Beatles’ career, ending just after the production of the White Album (1968). The second part begins by describing the tense final period of the Beatles’ heyday, and goes on to remember Harrison’s solo career, spiritual and social activities, and the mysteries of his private life. The documentary ends with his wife, Olivia, describing a “profound experience” at the moment of Harrison’s death, using terms that would surely have evoked one of the musician’s toothy smiles were he able to hear: “It was visible. Let’s just say you wouldn’t need to light the room if you were trying to film it. He just ... He just lit the room.”

Some viewers will dislike Scorsese’s approach. On one hand, die-hard Beatles fans won’t learn anything new during the first two hours of the documentary, which doesn’t even try to uncover untold anecdotes about the band’s rise to stardom or the heady days of the mid-60s. Nor is Harrison’s perspective particularly foregrounded; much of the early story is told with Lennon as its star (as in many Beatles documentaries), with Harrison defined more by his relationship to him and McCartney than by anything directly focused on the documentary’s subject.

On the other hand, audiences with only a casual acquaintance with Beatles history may find the film perplexing. There is no voiceover narration to hold all the elements together in an easily digestible form. When Scorsese provides captions for interviewees, he gives only their names. George Martin, for instance, speaks charmingly about the genesis of Within You, Without You with no real clarification of his role in the group’s career. Phil Spector remembers having his spiritual eyebrows raised by Harrison’s Hare Krishna Mantra record before the words “producer” or “Wall of Sound” are uttered on the soundtrack. And Sir John Stewart (“the Flying Scotsman) offers touching remembrances about Harrison’s state of mind after being stabbed during a 1999 home invasion without really clarifying his own relationship with the musician, or the musician’s interest in car racing. Other interviewees, like Neil Aspinall and Joan Taylor, will be names recognizable only to the most Beatles-literate viewers.

Scorsese sets the tone for this opaque approach from his very opening shots. Over footage that Harrison himself filmed, disembodied and unidentified voices bid him farewell, urging him to go on to the afterlife. Brief shots follow, in which unnamed interviewees are asked what they would like to say to Harrison if he could hear them. The subjects are not terribly difficult to identify (Eric Clapton, Terry Gilliam, Dhani Harrison, and Ray Cooper), but younger viewers or people without extensive exposure to popular culture may be perplexed right from the start.

Still, there is something beautiful, personal, and intimate in this enigmatic approach. As the documentary moves on, the focus becomes increasingly about what Harrison referred to as “the Art of Dying.” Scorsese tries to tap into the nonlinear, cyclic nature of Harrison’s philosophy, thinking, and use of language. Music from the later parts of Harrison’s career accompany some parts of the film, often connected to the historical narrative. As Tom Petty discusses Roy Orbison’s death, images of a very young George Harrison subtly remind the viewer that Harrison’s great success as a cultural icon was nothing less than an adolescent’s dream come true. And the home movies that raise the curtain on the documentary recur as the final, haunting images of the second half.

It is in its personal, elegiac moments of remembrance that Scorsese’s film is at its best, and where something deeply meaningful comes from the mouths of the interviewees. Archival footage of Harrison speaking lovingly of LSD is followed immediately with him remembering the Haight-Ashbury as “just a lot of bums,” which sent him running away from drugs as a source for enlightenment, and deeper into meditative practices. Scorsese juxtaposes this moment of disillusionment with Harrison’s discussion of first thinking of Eastern meditation while experiencing chemical enlightenment. The technique is one that carefully, in a nonjudgmental manner, chronicles the inherent messiness of Harrison’s discovery of what he thought of as the central, most important aspect of his life.

The other interviewees also offer tantalizing memories of Harrison that will be new to most viewers, although Scorsese cannily avoids making their intimate portraits of the musician too clear. Both Harrison’s former wives and the guru Mukundu Goswami speak hauntingly of the musician’s anger, without ever quite clarifying what they mean. Harrison’s longtime friend Klaus Voorman talks about Harrison “stepping back,” tantalizingly mentioning a period of deep personal trouble for the musician in the mid-1970s, but the topic is not further explored. And when Olivia Harrison talks about George lighting up the room at the moment of his death, nothing is pressed, no questions are asked. We are left uncertain whether she is speaking metaphorically, or whether she believes herself to have witnessed a sort of supernatural occurrence.

These ambiguities are at the heart of Living in the Material World. Scorsese’s film is like one of Harrison’s metaphors — a weeping guitar, a wall of illusion — something pregnant with meaning yet obtuse, obviously “in-the-know,” yet unwilling or incapable of imparting its knowledge without encumbrance. The documentary is a fitting artistic encapsulation of a private man who lived in the public’s gaze.