The historical canon is a cruel master. Consider how many composers have dedicated their lives to the Muse, perfected their craft, and scraped to make ends meet while producing quintessentially fragile and ephemeral works — the kind that need continuing care, re-inscription, and performance, to remain in the repertoire. Every musicologist daydreams of “discovering” an overlooked or forgotten composer (though most would likely be fine with unearthing a lost or unknown work by Bach or Beethoven) and when they do, we as listeners get to encounter a fresh new voice in a chapter we considered closed.

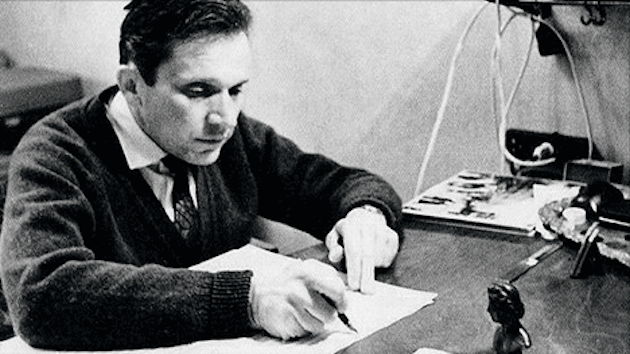

Polish-born, Soviet composer Mieczyslaw Weinberg is currently enjoying a rediscovery — or at least a re-evaluation, given that he was professionally established in Russia for most of his life, and produced over a hundred concert, chamber, and stage works. As the opener for their 25th season, Left Coast Chamber Ensemble presented Weinberg with a tribute concert that paired two of his chamber works with a more recent one by Krzysztof Penderecki (a younger and better-known compatriot), as well as two world premieres by California composers inspired by the life and music of Weinberg himself.

In the Sonata for Clarinet and Piano, Op. 28 (1945), Weinberg seemed to wear his stylistic traits on the sleeve, combining disarmingly memorable melodies, occasionally modernist harmonies, and conservative neoclassical forms with aplomb. The opening Allegro sounded at times as though it could have accompanied a period film, perhaps depicting a bustling street scene in Warsaw before the war. Left Coasters Eric Zivian (piano) and Jerome Simas (clarinet) gave a spirited reading, highlighting the occasional klezmer nod in the score with just the right amount of schmaltz. In the arresting finale, a sustained clarinet tone dissipated in a memorable and touching fashion.

The more recent Sonata for Solo Cello No. 4 (1986) failed to leave as favorable an impression. The composer’s late style seemed brooding and searching, less immediately captivating, and not as emotionally engaging, at least on first listen. The sonorous approach to the second movement, with its open strings and implied polyphonic writing, sounded like perfunctory homage to the first Bach cello suite. The contrast introduced by the use of the mute in the third movement had the adverse effect of putting aural brakes on the entire work, which sputtered to its end.

The new works commissioned by Left Coast for the occasion were Stephen Blumberg’s Concertino (for string quintet with violin soloist) and Julie Herndon’s Writing the Letter (for violin, viola, and cello). Blumberg entered a dialogue with Weinberg (a composer with whom he admitted unfamiliarity in the program notes) by incorporating fragments from one of the latter’s violin sonatas into the material for the new piece — a bit of an inside joke, given the relative obscurity of Weinberg material to most audiences. Regardless, Concertino was an effective and engaging piece, slender in its continuous five-part structure, which included moments of beautiful, sonorous stillness with more active ensemble playing, deftly navigated by Anna Presler and Jory Fankuchen (violins), Phyllis Kamrin (viola), Leighton Fong (cello), and Michael Taddei (double bass).

Presler, Kamrin, and Fong also performed in Herndon’s piece, which rather than relating to Weinberg’s music drew from the composer’s vicissitudes to reflect on the act of writing. Weinberg and his wife, separately and at different times, wrote poignant letters to Dimitri Shostakovich, asking for assistance as they fled from the Nazis during the invasion od Poland, and later when he found himself imprisoned after accusations of fomenting a Jewish insurrection in Crimea. In Writing the Letter, the physical act of writing provides the musical material for the piece, as the composer processed audio recordings of pen on paper to derive pitches as well as timbral and dynamic shapes. The resulting sound was a striking combination of heterophony and relation, as instrument and processed electronics blended to inhabit a surprisingly expressive space.

The program concluded with Penderecki’s Leaves of an Unwritten Diary (2008) presented here in the composer’s revision for string quintet. As the title suggests, the music is a sequence of loosely connected tableaux, widely ranging in character and emotion without offering much in terms of reflection or development, and cast in a generally conservative, neo-Romantic idiom. Yet — as much as I found myself missing the fiercely uncompromising Penderecki of old — the juxtaposition ends up sort of working, its extremes highlighted by the ensemble’s tightly coordinated performance. Similarly, Left Coast’s programming worked, both introducing us to a less familiar face in the canon, and drawing connections between the new and the recent — as important a job as breaking new ground.