What is music? John Cage aimed to stretch the conventional answers to that question by having us listen to everything around us. The Fluxus movement of the 1960s took things from there, devising scores and events that tried to obliterate the line between art and what passes for everyday life. They were rebels, outliers by definition, and their ideas remain controversial. Yet over half-a-century later, the mighty Los Angeles Philharmonic, a pillar of the cultural Establishment, gave over five hours of performance time at Walt Disney Concert Hall Saturday night to a Fluxconcert where, it seemed, anything went.

“The Concert Hall Is Not a Museum,” proclaimed the cover of a map that indicated where in the Disney Hall complex the events were taking place. But one can make a case that the Fluxconcert was as much of a museum as any regular symphony orchestra subscription season. A good deal of what went on consisted of pieces that are more than 50 years old, hardly what you would call “contemporary music.” Many — probably most — of the attendees were not even twinkles in their future parents’ eyes at the time Fluxus was going strong.

But it was a modern museum, an interactive one. And it was a lot of fun, simultaneously entertaining and serious.

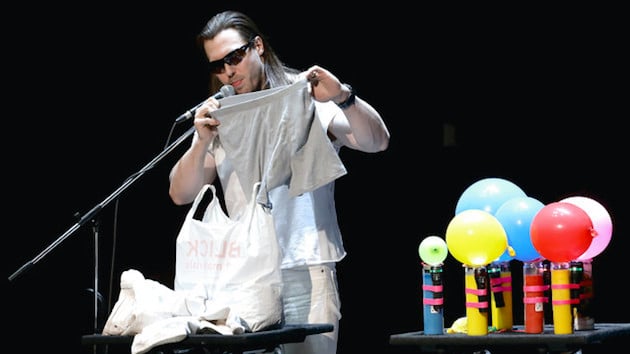

The fun started in the lobby where Fluxus curator Christopher Rountree devised a piece called Commitment Booth in which visitors were asked whether Fluxus events were music or not music, with an option for those who were undecided. BP Hall — temporarily renamed “Ben Patterson Hall” after a Fluxus pioneer — hosted a succession of Fluxus event scores like Yoko Ono’s Laundry Piece (describing the contents of a bag of dirty laundry), George Maciunas’s Manifesto (a battle cry for Fluxus by the man who gave the movement its name), or Ken Friedman’s recurring Telephone Clock (announcing the time). Outside on the rooftop garden, visitors could perform Pauline Oliveros’s Rock Piece by clicking two stones together, or participate in Ono’s Draw Circle Event by drawing circles on cardboard placards that would be mailed to Ono’s residence in New York’s Dakota building. And so on and so forth.

For hardy listeners inside the main hall, La Monte Young’s marathon proto-minimalist piece The Second Dream of The High-Tension Line Stepdown Transformer from The Four Dreams Of China (1962, revised 1984) proved to be a soothing sound bath as four pitches for eight muted trumpets and four cellos were sustained for nearly 88 minutes. (True, it did sound like a malfunctioning electrical transformer).

The other big work on the Fluxconcert didn’t even qualify as a Flux piece per se, as Luciano Berio was not a member of the movement. Yet his wonderful Sinfonia, with a tumultuous collage layered onto a Mahler scherzo as its centerpiece, is welcome on any program — especially when given as passionate and as rhythmically alive a treatment by Rountree, who led the Philharmonic and eight singers from Roomful of Teeth with his customary physical vigor.

The leadup to Sinfonia, though, was pure Fluxus, sometimes at its most extreme. The LA Phil’s First Associate Concertmaster Nathan Cole unwrapped some boxes to find a violin (Patterson’s Overture III), and was instructed by Young’s Composition 1960 #13 to Richard Huelsenbeck to play anything he wanted as well as he could (a Biber sonata). Then he smashed his instrument against a stage riser (Nam June Paik’s One, for violin solo), knocked his head against a wall (Ono’s Wall Piece for Orchestra to Yoko Ono), and left.

During intermission, the Phil paid a sentimental gesture to Cage by performing his American Bicentennial piece (which the Phil co-commissioned), Apartment House 1776, all over the building, all at the same time. There was a string quartet in the upstairs lobby, a horn sextet in the downstairs lobby, a quartet of baritone saxophones in the garden competing with someone singing Woody Guthrie’s “So Long, It’s Been Good to Know Yuh,” pairs of bassoons and oboes, and I’m sure I’m missing some components elsewhere.

Eventually, when cued by the pipe organ, everyone came into the main hall where the piece, based on recomposed American Revolution-era songs, continued grandly to a close. With all of the usual lobby hubbub now inseparable from the music, the Fluxconcert had achieved a Cage-ian communal spirit among listeners and performers that was difficult to resist.