The Los Angeles Philharmonic was at the top of its game in an evening of (mostly) French music on Sept. 3 at the Hollywood Bowl. French-born conductor Ludovic Morlot led music by Hector Berlioz, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet, and Igor Stravinsky — Russian-born but working in Paris at the time he composed Petrushka. Morlot navigated the music admirably, adapting his conducting style as the pieces progressed.

Berlioz’s Roman Carnival Overture was a jolt of energy for the listeners in the less-then-filled Hollywood Bowl. Rapid violin passages led to bursts of brass and timpani, a muscular and full sound that played well with the sound system.

LA Phil concertmaster Martin Chalifour performed as soloist, playing Chausson’s Poème and Massenet’s “Méditation” from Thaïs, which he pulled off with a smooth and singing tone. He was at his best in the instrument’s upper register, perhaps due to the amplification system in the Hollywood Bowl.

It’s interesting to watch a soloist perform with an orchestra to which he has belonged for more than two decades. Most soloists appear with a different orchestra each night, but Chalifour has an exceptional understanding of the LA Phil’s sound. He was able to place his tone where he wanted, at times blending and at others standing out.

Chalifour encored with the Presto from J.S. Bach’s Sonata No. 1 in G Minor. While disconnected from the rest of the programming in terms of century and style, he played with coolness and control on Bach’s faster passages that require an agile bowing technique. He took the Presto slower than usual, but used the slower tempo to heighten the string-crossing in the piece.

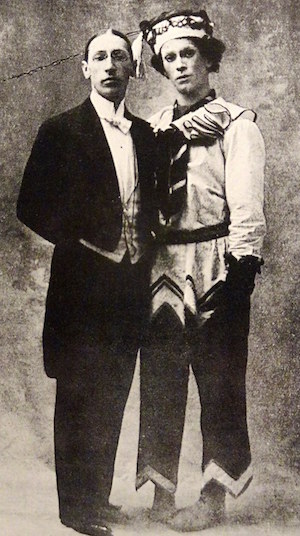

Petrushka (1911) formed the second half of the night. It made sense to end an evening of French music with this work, which stands at the start of modernism in the early 20th century. Petrushka capped the program nicely, showing us the direction in which French music moved.

Petrushka serves as the bridge between Stravinsky’s other two early ballets: The Firebird and The Rite of Spring. With Petrushka, we hear a young composer finding his footing as he experiments with orchestration. Morlot gave a bright and athletic account and did well to highlight Stravinsky’s exploration of color. Some pieces are made by their melodies, but the magic in this one lies in the orchestration.

The beginning of the fourth movement, filled with repetitive lines in the strings, points towards the minimalism of the later 20th century. These passages glisten, and Stravinsky’s love for short bursts of brass is on full display. The percussionists of the LA Phil gave a standout performance, as did principal trumpet Thomas Hooten. He navigated folksy, almost child-like melodies, but with devilish virtuosity.

Morlot’s aptitude for rhythmic nuance and slight tempo variations yielded a performance that felt both in-control and spontaneous. It seemed a natural approach to this score that has countless moments to showcase individual musicians. Rather than dictating the tempo, Morlot allowed the instrumentalists the chance to bend time for their particular musical moment. It is a modern conducting approach, in which the conductor is not a dictator but a moderator.