Photos by Kristen Loken

The public phase of the 2013 Merola Opera Program has opened in a good new venue, with a brilliant musical production of one of Benjamin Britten's finest but relatively little-known works.

Most of the Merola Program is behind the scenes, with coaching, master classes, day-'round hard work for the young artists. How well all that is paying off already was clear at the thoroughly professional production of Britten's The Rape of Lucretia in the unfamiliar setting of the Everett Middle School Auditorium.

With Herbst Theatre closed for renovation, this auditorium is a pleasant surprise, providing excellent acoustics and sightlines well above expectations, and definitely superior to another Merola venue, Fort Mason's Cowell Theater. Be ready to make your acquaintance as the other Merola performances — until the Grand Finale in the Opera House — will also take place here.

Britten's 1946 chamber opera, following closely his career-making Peter Grimes, is dramatically and philosophically a strange and debatable work, but musically it's ravishingly rich (serving well for Kathleen Ferrier's historic debut). Complex and yet easily accessible, the music contrasts the ugliness of the subject with sublimely beautiful passages.

As in Peter Grimes, musical highlights belong in the orchestra, and the small ensemble of a dozen (plus Merola participant Timothy Cheung on piano) performed surpassingly well, under Mark Morash's baton. He was faithful to the spirit and letter of the score, and yet imbued it at times with an unusual, and very welcome, intensity and romantic abandonment. The hall's only acoustical weakness, a minor one, can be heard only in moments of Morash's Wagnerian fortissimos when the sound momentarily loses its clarity becuase the otherwise good reflection from the high ceiling becomes saturated.

As the orchestra consists of soloists rather than sections (one first violin, one cello, etc.), they well deserve individual mention, and the players are listed at the end of this review.

Britten, with his lifelong militant pacifism, was especially vocal in denouncing war and violence in the wake of the great bloodletting many others have regarded as a "necessary war." Ronald Duncan's libretto — both poetic and convoluted — serves Britten well as the composer is dealing with debauchery in Roman times in terms of Christian morality.

To be fair, long before Britten, St. Augustine, in his 5th century The City of God, weighed in on the state of Lucretia’s soul, pronouncing her innocent of adultery, but guilty of the greater sin of suicide.

Duncan's libretto is based on Titus Livius Patavinus' history, the 1594 Shakespeare poem The Rape of Lucrece, and the 20th-century French play by Andre Obey, Le Viol de Lucrece. Bracketed by a statement that the story took place 500 years before the birth of Christ and an epilogue of devotion to Christianity, the story is about the Etruscan prince Tarquinius Sextus and his violation of the virtuous Lucretia, devoted wife of the Roman general Collatinus.

Interspersed between historical references to the Etruscans' role in Roman history, hideous verbal debasement of women, and the incongruous Christian context, the rape of the title is the story. The first act leads up to it, the second act begins with it, the finale and epilogue deals with its consequences (which included Rome's successful overthrow of Etruscan rule).

What you take away from the opera, however, is the robust music of Tarquinius' ride to Rome; the beautiful night music of the Act 1 finale; the gloriously complex music of contradictory and conjoining motifs throughout the work of angular, brutal sounds, intricate figures, and melting beauty, contrasts similar to those of Strauss' Electra. Devices such as Lucretia's six-note theme (an ingenious quintuplet-plus-upbeat on the piano, played as an elegant, wistful ostinato by Cheung) drive the music home powerfully.

Wisely eschewing period costumes, Peter Kazaras' direction places the work in the setting of a military court. The two narrators/interpreters/commentators — the Male Chorus and Female Chorus — and the men appear in uniform. To Kazaras' credit, he doesn't force the material into the framework, leaving even the appearance of Tarquinius, as the defendant, ambiguous.

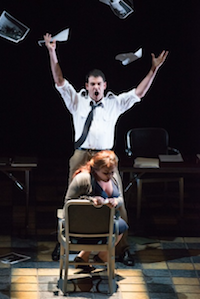

The director also allows the text to tell the story, refraining from enacting the movements it describes. Kazaras acted like a good choreographer, who doesn't fall for the one-note-one-step mechanical monotony. The only directorial device that was unclear — at least to me — was quires of paper thrown about on the stage, first to express Tarquinius' lustful rage, later to represent flowers.

Thanks to Merola coaches and the young singers' efforts, diction in this rather talky opera is outstanding, making supertitles unnecessary, but perhaps appreciated by many accustomed to "reading the opera." The problem in such a situation is that it's difficult to resist reading the supertitles even when you understand pretty much every word.

In the first act, Lucretia is mostly seen, not heard. But in the second act, when the title role really comes into its own, Kate Allen gave a spirited, thoughtful, appealing performance, the voice filling the house, a diva in the making.

Chris Carr's Tarquinius was a dramatic coup, but his voice and vocal performance were of even greater interest. Even singing a brutal character, with steel and storm in the voice, there is warmth and beauty in his baritone — a rare, precious combination.

The first voice heard in the opera is Robert Watson's as the Male Chorus, and it made the audience sit up and pay attention, something that continued throughout the performance. The tenor's voice has Presence, with a capital P. When later on, Linda Barnett joined him as the Female Chorus, the two carried these vital roles in a splendid fashion all the way through the work.

David Weigel, as Collatinus (Lucretia's wronged and forgiving husband), Efrain Solis as Junius, Katie Hannigan and Alisa Jordheim as Lucia (Lucretia's servants) sang impressively individually and as an ensemble.

Look out for the next public Merola event, the Schwabacher Summer Concerts on July 18 and 20.

And kudos to: Tatiana Freedland (violin I), Carol Kutsch (violin II), Melinda Rayne (viola), Mary True (cello), Ken Miller (bass), Stephanie McNab (flute/piccolo/alto flute), Deborah Shidler (oboe/English horn), Tony Striplen (clarinet/bass clarinet), Daniel MacNeill (bassoon), Susan Vollmer (horn), Wendy Tamis (harp — with a prominent role), Kent Reed (percussion).