The Violins of Hope, a collection of string instruments that survived the Nazi Holocaust in the hands of Jewish internees or refugees, made a return visit to Kohl Mansion in Burlingame on Sunday, Feb. 16, as part of the project’s current Bay Area residency. This time the instruments were in the hands of the Ariel Quartet, founded 20 years ago in Israel and now faculty quartet-in-residence at the University of Cincinnati.

To acknowledge the harrowing history of these instruments, the Ariel programmed them in two of the grimmest, most death-obsessed string quartets in the repertoire: Schubert’s Quartet No. 14 in D Minor (“Death and the Maiden”), D. 810, and Shostakovich’s Quartet No. 8 in C Minor, Op. 110. Schubert’s work is said to be his response to facing a fatal illness at a young age. Shostakovich’s is publicly dedicated to the victims of fascism and World War II, while privately the composer intended it as a self-eulogy. These works are uncompromisingly searing.

Anyone familiar with the Ariel’s way with other dark and dramatic music would have found no surprise, but plenty of excitement, in its handling of the Schubert. This performance burst with exacting tension and drama throughout. Quieter intervals appeared as tiny lakes of calmness, but without relaxation, because the furious intensity could return at any moment, and inevitably did.

The second movement theme and variations, based on Schubert’s song “Death and the Maiden” (hence the quartet’s title), was so emotionally wrenching in its shifting successive moods that the performers’ greatest achievement lay in avoiding letting the two succeeding movements turn into an anticlimax.

They did this by not conceding an inch to the liveliness usually heard in the Scherzo, or the jollity that similarly infects the finale. In the Ariel Quartet’s hands, these movements were just as serious and dramatic as their predecessors.

The group’s approach to the Shostakovich work was different. Here the goal seemed to be to take the five connected but contrasting movements and weld them into a unified whole. The dramatic moments in this work were emphatic but not sudden or startling. The contrasts were strong but not made to sound overwhelming or to lunge at the listener.

The Ariel Quartet are the fourth set of performers I’ve heard on the Violins of Hope during the current busy residency. The mastery of the Ariel’s musicianship is so great that in this concert I felt that the instruments were being pushed up against the limits of their technical quality as musical instruments.

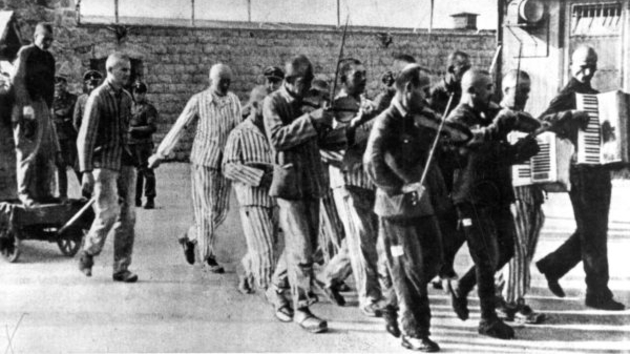

The Violins of Hope have, of course, been collected because of their history, not because they’re necessarily of high quality. Most of them are modern-make, ordinary workaday instruments. In this concert, limitations to the instruments’ depth and resonance, in the richness of their sound, became audible.

The players, however, made the most of what they had to work with. In the third movement of the Shostakovich, playing continuous plain rhythmic figures, violist Jan Grüning cultivated a dry and boxy texture that he might not have achieved with a higher-quality viola. Here a cold, mechanical tone was appropriate for the music, and it came out vividly.

Throughout both quartets, the players emitted unexpectedly rich harmonies entirely dependent on their skill at manipulating the instruments they had in hand. Held chords in the Schubert jumped out like starbursts. Repeated bursts of heavy chords in Shostakovich’s fourth movement, often compared to the KGB knocking at the door, came out with strong, distinctive, and varied tone colors at each appearance.

The group as a whole emphasized the rich fullness of the ensemble rather than individual voices, although in the Schubert the distinctive bass line of cellist Amit Even-Tov came out conspicuously. This is a quartet more concerned about the total effect of the ensemble rather than the sound of individual instruments. That approach assisted in getting the best possible result out of the Violins of Hope.

The concert was completed with an unusual item: Prokofiev’s Sonata for Two Violins in C Major, Op. 56. Composed in 1932, this piece uses neoclassical techniques to modernistic ends, and seemed to the Ariel players to be a child of its time, the time that also gave rise to the totalitarian persecutions. The quartet’s two violinists, Gershon Gerchikov and Alexandra Kazovsky, played this work with a touch of the lightness they expunged from Schubert’s closing movements. Prokofiev’s various ways of intertwining the violin lines were reflected by variations in performing color, which Gerchikov and Kazovsky exchanged back and forth with brilliant invention.