The Music@Menlo festival is renowned for its authoritative readings of great chamber music classics. Sometimes, though, it will surprise listeners by unearthing little-known treasures and playing those equally well. At the August 2 concert at Menlo-Atherton’s Center for the Performing Arts, the treasure was Fritz Kreisler’s String Quartet in A Minor, composed in 1919.

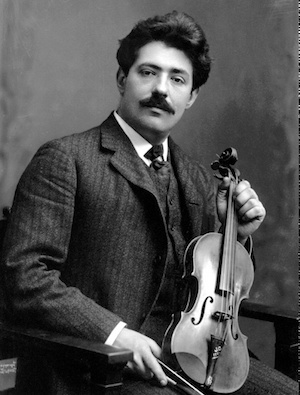

Kreisler (1875–1962) is the presiding spirit of this year’s festival, celebrating “The Glorious Violin.” One of the great violinists of his time, Kreisler is being honored extensively in the program, including with several concerts including his own compositions and other music that he played. Wednesday’s main series concert, titled “The Age of Expression,” is one of these, and the four-movement String Quartet is the largest-scale work of his that the festival is presenting.

Despite its authorship by an acclaimed violinist, the quartet is not a violin-heavy work. The few extensive display solos were all for Nicholas Canellakis’s cello. The two violinists, Benjamin Beilman and Danbi Um, played mostly closely-knit duets, their lines often separated by chromatic intervals making for that rich, expressionist harmony that the concert’s title led the listener to expect. Whenever Beilman did have a solo phrase, it was usually echoed by Um and violist Paul Neubauer as well.

Written in a harmonically expansive but consonant style with a tinge of Viennese nostalgia, the Quartet is fairly concise, within its full scale. It lasts about 27 minutes and doesn’t wear out its welcome. The players gave it a cool, restrained performance, low on vibrato and tempo fluctuations, high on intense instrumental color. The lightness of the scherzo, in particular, was characteristic of a rendition that moderated the weight of the work’s harmony.

Beilman played, entirely from memory, another work associated with Kreisler, the Sonata in E Minor for Solo Violin, Op. 27, No. 4, by Eugène Ysaÿe. Dedicated to and first performed by Kreisler, this piece from 1924 is a neo-Baroque homage, and Beilman emphasized that quality. He played with clarity, shaping the phrases with clean separations. The piece has many, brief double-stops, which here emerged like shafts of differing colors flashing out through the music.

The other half of the concert sounded entirely different. The principle here was that expressionism is a style of performance, not just one of composition.

Neither of the pieces played were especially expressionist in compositional style. Borodin’s String Quartet No. 2 in D Major is a lyrical outpouring of high Romantic melody, with fully consonant but not over-ripe harmony. Respighi’s Violin Sonata in B Minor, totally unlike his more famous, crispy, neo-Baroque works (or Ysaÿe’s), is similarly Romantic, relaxed, and rhapsodic.

But both works were played with impassioned emotionalism of the kind often heard in Schoenberg or Berg. In Borodin’s quartet, extremely heavy vibrato, especially from cellist Clive Greensmith, combined with impassioned tempo fluctuations and catches in the phrasing, particularly from Danbi Um on first violin, to make a vividly lush, hothouse rendition. Only Neubauer on viola gave anything like the restraint he brought to the Kreisler. The harmonies, in combination, tended toward the sweet, even the luxuriant. If the object was to move Borodin from the 1880s to the more “decadent” era of two decades later, it succeeded.

Paul Huang, who was second violinist in the Borodin, joined with pianist Orion Weiss for the Respighi sonata. Huang brought abrupt intensity to his part, playing with heavy bowing in strong passages and more smoothly in lighter phrases. Weiss struck a careful balance in his equally heavy piano part. His playing was strong and declarative, with clear chording. His style was too regular to be rhapsodic, and too firm to be impressionistic. It kept the rambling score balanced and on track and cut back on the more emotive side of Huang’s work.

This bifurcated concert showed that there are a variety of ways to express a musical age, even one of expressionism.