Standing convention on its head, György Ligeti’s unique, extraordinary 1997 re-visioning of the Requiem celebrates more the music of sound than the other way around.

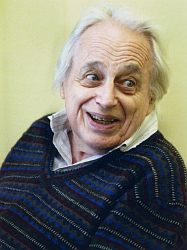

Ragnar Bohlin's Symphony Chorus, and the orchestra under Music Director Michael Tilson Thomas' direction went from triumph to triumph in performing the "unperformable" Ligeti. Ominous murmurs at the threshhold of audibility, high notes forcing the first sopranos into falsetto, the densest harmonies, all kinds of polyphony, "moving around in half- and whole-tone steps, mixed in a way so that you easily get lost, climbing up and down in quintuplets, six-, seven- and even nine-tuplets" — and that’s just a starter’s list of the piece’s formidable difficulties.

And yet this is not an exercise, no thumbing a nose at the audience. On the contrary, it is a great, gripping work, entirely appropriate to the four sections of the Requiem it illuminates: the Kyrie [Introit], De die judicii sequentia (“Day of judgment sequence," for example, the Dies Irae), and Lacrimosa. From the super-quiet early portions, the music escalates into what Ligeti himself has called a "hysterical and hyperdramatic" sound. But here again, it's not empty effect or posing, but great dramatic music or, rather, sound.

Hannah Holgersson was the adequate soprano soloist, Annika Hudak the superb mezzo. This was the San Francisco premiere for the Requiem and the reception was warm and loud.

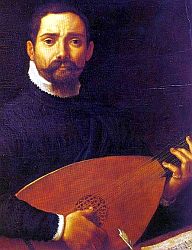

Bohlin himself conducted the program-opening "Ligeti warm-up piece," the Venetian Giovanni Gabrieli's In ecclesiis (circa 1585), with part of the Symphony Chorus on the stage and the rest flanking the audience on the two outside aisles. The attempt to match the sound of divided choirs in a cathedral worked, and sound enveloped and embraced the audience.

It would be nice if the promise of the Ligeti (and perhaps the program-closing 1854 Liszt Tasso, with all its bluster), filled the hall, but that was not the case. The main attraction was the Queen — no, Goddess — of Piano, Martha Argerich, and she fulfilled even the wildest expectations.

Besides having heard the Ravel Concerto umpteen times, this was my fourth live performance with Argerich as soloist, and yet I'd swear I never heard the work before. Listeners always describe her playing with words like “clear, singing, effortless”, and “natural.” But what takes her into the hyperspace of pianists is the way she seemingly invents the music as she goes along.

Steely fingers in the opening Allegramente, fragile and yet secure poetry in the Adagio, and throwaway bravura in the Presto mark many a great pianist. The ephemeral extra for Argerich is the utter innocence of it all — no posing, no calculation, no playing for effect: It is what it is, and it is all thrillingly authentic and beautiful.

Inspiring orchestra and audience alike, Argerich conjured instrumental solos of unprecedented excellence from her adoring colleagues. Woodwinds and brass have never been better. Until she performs the concerto again, this will be the definitive performance.

There were six curtain calls, and what MTT termed an unprecedented reprise of the last movement. (He must have meant during his 14 years here; in the good old days, repeats were given often.) Would that Argerich had played the whole concerto again, the orchestra dispensing with Tasso instead.