Disney's Dinosaur Desert

Music Director Alasdair Neale began the program with the Puerto Rican composer Roberto Sierra's Carnaval, named in part for quotations from Robert Schumann's piano piece of the same name, but also because of the mythical menagerie (à la Camille Saint-Saëns Carnival of the Animals) depicted by its five movements. “Gargoyles” boasts busy buzzing and bongos; “Sphinxes,” some vague orientalisms, distant brass flourishes, bass-drum rolls, and a quickish dance with tambourine. “Unicorns,” reported by Sierra to be inspired by the tapestry The Lady and the Unicorn, brought some welcome romantic contrast. “Dragons” returned to sounds indistinguishable from the first two movements while “The Phoenix” concluded with an Arabic-tinged, mambolike dance with plenty of drums.

Sierra's piece is one of the commissions of Kathryn Gould's welcome Magnum Opus project. Although reported in the program notes as being premiered last year in Oakland “to great acclaim,” such was not the mild reception from the Marin Center Auditorium attendees. Listeners I spoke to during intermission complained of lack of melody and insufficient contrast between movements. The question “How is a gargoyle different from a sphinx?” was not answered. To me, while there was a fair amount of rhythmic interest, the orchestral texture languished all too often in thick and heavy territory. I don't know if the problem is endemic to the score, or could have been corrected by Neale with balance adjustments in additional rehearsals.

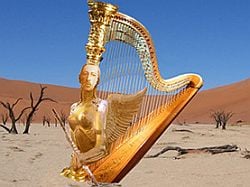

Lucid Harp and Flute

Fortunately, the lucid miracle of Mozart's Concerto for Flute and Harp in C Major, K. 299, was next on the docket. For the most part, Daniel-Barker's flute was charming, I only missed a bit more emphasis on some of the high points of her phrases. Even more delicious was Levitan's brilliant gold instrument, which came through wonderfully on time and over budget — I simply can't get enough of the harp part in this piece!

True to the polyglot theme of the concert, Daniel-Barker and Levitan came up with an interesting mix of cadenzas for the three movements: six segments mixed and matched from those by four composers other than Mozart. Most intriguing was the cadenza to the finale, which began with one by the composer I call “Mr. Blendable,” Carl Reinecke (1824-1910), but then morphed into pleasantly unusual if anachronistic harmonies by the Dutch musicologist Marius Flothius (b. 1914).

After intermission came my imaginary animals, the dinosaurs from Disney's Fantasia, forever wired into my aural/visual neural pathways via Igor Stravinsky's Rite of Spring. This, of course, is one of the most important and devastating compositions of all time, and it remains a challenge for conductor and players alike after 96 years of ubiquity. To put matters simply, Neale and his band did not emerge unscathed by the end of the work. Part 1 faltered here and there, but to his credit Neale brought it to a strong conclusion, and had an even better final touch for the very end of Part 2.

The last notes of Part 2 have been a concern to critics ever since Cecil Gray in the 1920s complained that the piece “suddenly falls over on its side with a lurch.” The usual reaction from inexperienced listeners is, “What, it's over?” Some writers point out that in the ballet, the audience sees the sacrificial dancer die from exhaustion, but that visual aid isn't there for concertgoers. (Ballet fans were treated preconcert to some dancing in replicas of the original costumes designed by Nicolas Roerich.)

Neale solved the conundrum of the last three bars with a nicely stretched out ritard there — one not in the score — and the conductor scored very high in my book, and helped bring the audience to their feet.

Are Both Parts Really Necessary?

Now, here's a question I've been mulling in my head the last few years over concerts of this two-part ballet: Wonderful as the music is, do we really need Part 2 for the concert version? Does it add anything we haven't got already in Part 1? I know, I love to hear the dinosaurs drop one by one as they march through the desert in the “Ritual Action of the Ancestors.” But couldn't that just as well have been a separate piece, Rite of Summer? Responses solicited.