Classical audiences love a succès de scandale — no program note for The Rite of Spring would be complete without a regaling account of its riotous opening night. While there’s a certain satisfaction in seeing how much our tastes and tolerance-levels have developed in the last century, it would be thrilling if composers today could still incite uproar using only their music. But we’ve heard it all; not even the sound of John Cage’s silence fazes us anymore.

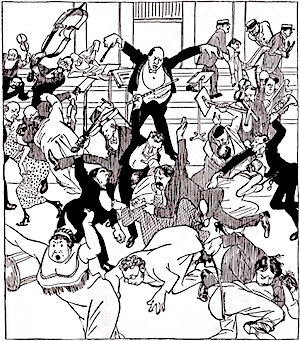

In 1913, a few months before the Rite premiere, Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony No. 1 (1907) provoked a notorious Skandalkonzert that ended prematurely with flying fists and flung furniture. Mercifully, Elevate Ensemble’s Saturday-night performance of the piece at SOMArts Cultural Center was met with a far less violent reaction. But the group did manage to channel the energy of an all-out brawl into their exhilarating interpretation.

There was an overwhelming sense of danger in the way director Chad Goodman pushed the players to expressive extremes. The first half of the Schoenberg, especially, was a wild ride — aggressive Brahmsian and Mahlerian melodies from the 15 soloists overlapped in a bustling, breathless counterpoint. There were moments when the polyphony grew so dense and complex that it felt like a single missed entrance might unravel the whole texture.

Yet this wasn’t some messy free-for-all — Goodman charted a clear formal trajectory, taking his time with the ascending stacks of fourths and Tristan-like pillar chords that serve as structural markers throughout the piece. The conductor mentioned that Schoenberg’s instrumentation is a tad awkward, with five string players competing with 11 blaring winds. For the most part, the ensemble achieved an ideal balance, but there were a few points when squawking woodwind themes intruded on some particularly lovely string playing.

Cellist Gabriel Beistline executed his Wagnerian solo passages with voice-like lyricism, and clarinetist Carlos Ortega reveled in Schoenberg’s grotesque, proto-atonal outbursts. Elevate offered a performance brimming with ecstasy up until the triumphant finale, crowned by Gina Gulyas’s peeping piccolo descant.

Preceding the Chamber Symphony on the program was a world premiere for the same instrumentation by the ensemble’s composer-in-residence, Julie Barwick. Her Sinfonietta was a response to Schoenberg’s Chamber Symphony, but in a more playful vein.

The first of the five attacca movements opened promisingly with a slithering, ascending run for E-flat clarinetist Sophie Huet, reminiscent of the first measures of Strauss’s Salome. Various players picked up the theme, rising up one after another in quick succession. All the while, the ensemble radiated halo-like harmonies that slowly shifted in timbre and pitch. This iridescent texture, paired with the snaking solo lines, produced a mysterious, film noir atmosphere that was over too soon.

While the remaining four movements differed from one another in character, they unfolded more-or-less along the same lines: a soloist would introduce a small melodic cell that was then echoed over and over by other members of the ensemble. Compared with the rich thematic variety and development of the Schoenberg, Barwick’s motivic treatment felt a tad simplistic. The constant instrumental parroting called to mind the seagulls from Finding Nemo, with their endless repetitions of “mine!”

It would be unfair to compare her work to the Schoenberg — Barwick didn’t set out to replicate the Chamber Symphony, but rather to create a light-hearted, quasi-symphonic suite “in my own language,” as she put it. And she succeeded on many fronts. A pentatonic motive in the second movement generated a bubbling, Debussyian texture as the soloists passed it around. The Stravinsky-like third movement established a driving string ostinato punctuated by syncopated attacks on jazzy chords. While the final movement was lovely, its open fifths and typically “American” sound relied too much on Aaron Copland’s prairie-evoking style.

The concert also featured the winner of Elevate Ensemble’s 2017–2018 call for scores, Florida-based composer David Lipten’s Tongue & Groove. Aside from its naughty sexual implications, his title referred to the piece’s grooving, dancelike rhythms and the articulatory tonguing technique of the oboe soloist. Elevate’s five string players joined Ryan Zwahlen in a kind of oboe concerto in miniature.

John Adams-style riffs in the strings built up in head-bobbing accompaniments that resembled authentic electronic dance music — some passages sounded like something you might actually get down to at a Castro club. Zwahlen fell hard on the on the off-beats for his salsa-like solo line, suddenly digressing into bizarre, agitated tantrums that had a slightly sinister quality.

However, the mischievous “bite” in his playing softened into something more elegant and refined as the ensemble transitioned into an 18th-century pastiche that seemed like a parody of the slow movement from Mozart’s Oboe Concerto. Every so often, the dance riffs tried to take over again, anticipating an odd moment when the ensemble broke off from this Viennese imitation entirely and returned to the catchier opening material.

Lipten’s enigmatic little work left a question mark hovering, with its postmodern juxtaposition of “high” and “low” art, old and new. The disintegration of his Mozartean pastiche came across a rejection of outdated European Classicism in favor of the thumping rhythms of today’s living, breathing genres — ironically scored for a chamber ensemble. Whatever it meant, I certainly enjoyed it.