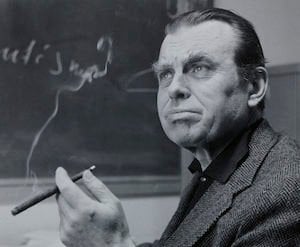

Only those with heads buried deep in the nuclear sand may fail to understand why music rooted in the Holocaust speaks so clearly to our present-day realities. On their third recording, Once/Memory/Night: Paul Celan, Bay Area chamber group Ensemble for These Times (E4TT) proves the relevancy of their name by recording three commissions that set the deeply unsettling poetry of Holocaust survivor Paul Celan (1920–1970) and his contemporary, Nobel Prize winner Czeslaw Miłosz (1911–2004).

Somewhat deceptively, the recording begins with Libby Larsen’s mostly upbeat, 10-minute 4½: A Piano Suite (2016). Fetchingly performed by E4TT guest pianist Xin Zhao, its five movements are easily accessible, rhythmically engaging, extremely beautiful, refined in places, and ultimately playful. Save for the short fourth movement, In Memoriam, they soften you up for the seven movements of composer and E4TT co-founder David Garner’s Die eichne Tür (The oaken door, 2017) that follow. Performed by soprano and E4TT co-founder Nanette McGuinness, guest English hornist Laura Reynolds, violinist Ilana Blumberg, cellist Anne Lerner, and Xin Zhao, Garner’s Die eichne Tür includes settings of five deeply personal poems by Celan that, in English translation, are anything but an easy ride.

Somewhat deceptively, the recording begins with Libby Larsen’s mostly upbeat, 10-minute 4½: A Piano Suite (2016). Fetchingly performed by E4TT guest pianist Xin Zhao, its five movements are easily accessible, rhythmically engaging, extremely beautiful, refined in places, and ultimately playful. Save for the short fourth movement, In Memoriam, they soften you up for the seven movements of composer and E4TT co-founder David Garner’s Die eichne Tür (The oaken door, 2017) that follow. Performed by soprano and E4TT co-founder Nanette McGuinness, guest English hornist Laura Reynolds, violinist Ilana Blumberg, cellist Anne Lerner, and Xin Zhao, Garner’s Die eichne Tür includes settings of five deeply personal poems by Celan that, in English translation, are anything but an easy ride.

Despite music that is quite haunting in places — the manner in which Garner ends the cycle is especially effective — the performance falters due to the soprano’s borderline shrill sound. Most effective at the bottom of her range, where she successfully communicates to chilling effect, her instrument’s lack of warmth and incipient warble do not invite listeners into settings that include the lines, “Oaken door, who lifted you from your hinges? / My gentle mother cannot come back.”

Despite the unsettling nature of the vocals, the two songs that comprise composer Jared Redmond’s Nachtlang (Nightlong, 2017) are especially effective because words and music are so closely aligned. The chilling essence of the first song, “Notturno” (Nocturne), is rendered all the more effective by McGuinness’s skillful deployment of her low range.

The recording ends with a double gift. Anthony Miłosz, who translated his father’s poem, “A Song at the End of the World” (1944) into English, brings an air of authenticity to the presentation by reciting the words. Then, McGuinness sings Stephen Eddins’s eponymous six-plus-minute setting from 2018, with accompaniment by Lerner and Xin Zhao. This is far more accessible poetry and music, with nothing hidden, and the music is as direct as it is moving. Unfortunately, Eddins asks his vocalist to do what few vocalists can do effectively, which is to recite some of Miłosz’s words. Few singers can successfully make the transition from speaking to singing without sounding self-conscious. It’s a false step in an otherwise strong composition.