Editor's Note: Gordon Getty is a funder of SFCV.

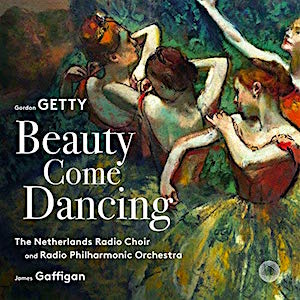

Beauty Come Dancing, on the Pentatone label, is an attractive collection that confirms Gordon Getty’s twin loves of composing for voice and making poetry into music. Even those familiar with Getty’s operatic settings of Shakespeare (Plump Jack) and Poe (Usher House) may be unaware that the composer studied English at the University of San Francisco before earning a bachelor’s degree at the San Francisco Conservatory of music and setting the verses of Alfred Lord Tennyson and Emily Dickinson in song. The poets assembled here range historically from Lord Byron to John Masefield to Getty himself, and the music in many aspects is as varied as the verse, unified by the composer’s self-declared affinity for 19th-century tropes of elegance and romance, and his flair for the dramatic.

These qualities are airily and engagingly conveyed by the Netherlands Radio Choir and the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by James Gaffigan, and are evident in Getty’s own poetry, the source for the album’s first two offerings. “The Old Man in the Night” showcases the full instrumental and vocal ensembles in a gentle and reflective account of an interchange between two characters at opposite ends of their lives. “The Old Man in the Morning,” written more recently, elicits plaintive accompaniment on English horn, harp, and strings. Love is an abiding theme here for both poets and composer, as is dance, first manifest in Getty’s take on John Masefield’s “Ballet Russe.” The poem references Chopin, and Getty, in the liner notes, has stated his “aim for tunes Chopin might have written, but didn’t.”

These qualities are airily and engagingly conveyed by the Netherlands Radio Choir and the Netherlands Radio Philharmonic Orchestra, conducted by James Gaffigan, and are evident in Getty’s own poetry, the source for the album’s first two offerings. “The Old Man in the Night” showcases the full instrumental and vocal ensembles in a gentle and reflective account of an interchange between two characters at opposite ends of their lives. “The Old Man in the Morning,” written more recently, elicits plaintive accompaniment on English horn, harp, and strings. Love is an abiding theme here for both poets and composer, as is dance, first manifest in Getty’s take on John Masefield’s “Ballet Russe.” The poem references Chopin, and Getty, in the liner notes, has stated his “aim for tunes Chopin might have written, but didn’t.”

Like his Polish pianist-composer predecessor, Getty’s pacing and coloration sound choreographed, the arpeggiated piano sparkling at the center of the choral display, partnered by harp and strings. “Shenandoah,” though its lyric lies in folklore, may be one of Getty’s most affecting single pieces to date. The refrain’s “rolling river” is audible in the swells and runs, the harmonic arrangement alluring and rustically fresh and unaffected.

The affect for John Keats’s “There Was a Naughty Boy” is appropriately jumpy and playful, in short lines like a child’s story song. The only setting for women’s chorus is matched to “Those Who Love the Most,” the only poem by a woman, Sara Teasdale. The music invokes the magic in the poet’s mythic name-checks and palpably positions love as triumphant. For the album’s titular “Beauty Come Dancing,” from a poem by the composer, Getty trickily pairs iambic pentameter with waltz time, with giddy accompaniment by flutes, clarinets, celesta, and strings. The waltz sobers up for Edwin Arlington Robinson’s “For a Dead Lady,” in an alluring setting for chamber orchestra that ends artfully unresolved.

There follows another compelling change of scene on Lord Byron’s epic of “The Destruction of Sennacherib,” the selection perhaps most evocative of the masterful mustering of the individual sections and instruments of the orchestra apparent in some of Getty’s operatic writing. It’s arguably also the composer’s closest approach to advanced 20th-century chromatic modulations and anguished voicings. The tale of “Cynara” is the work of “Decadent” poet and novelist Ernest Christopher Dawson, but Getty’s deployment of men’s chorus and chamber orchestra, effectively dramatic, honor’s the poet’s febrile longing but avoids the garish. Keats returns for the closer, “La belle dame sans merci,” with which Getty takes on another of his favorite roles, unabashedly sustaining single notes or chords when they serve as storyteller. In an ironic twist on Keats’s “wither’d sedge” where “no birds sing,” Getty commands a clarinet to sing anyway. All the poetry appears in the album’s booklet, making for a satisfying celebration of two forms of creative expression.