It has been nearly half a century since San Francisco pianist Garrick Ohlsson became the first American to win the Chopin International Piano Competition. With a recent appointment as faculty at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, Ohlsson may be spending more time at home but maintains a full international tour schedule.

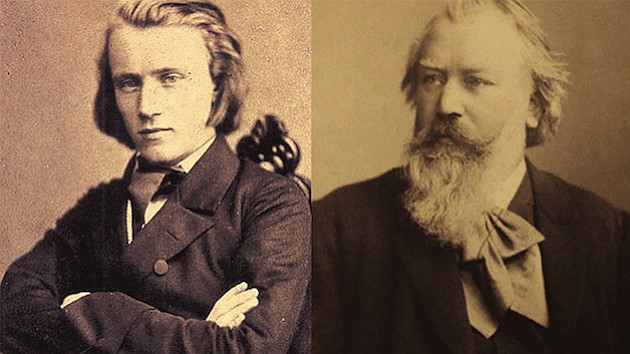

The pianist has recently embarked on a multi-year project to cover the entire piano repertoire by Brahms and the fans who filled the Herbst Theatre on Thursday witnessed a fascinating juxtaposition of Brahms’ early works with his later ones.

Brahms’s second sonata, Op.2, is the second of two ambitious, grand-scale sonatas that he wrote to proclaim his voice to the world. Ohlsson painted the valiant and tragic lines with bold, explosive colors, yet with his signature sense of ease. The sorrowful andante sang wistfully, with answers sounding ethereally like a music box. Yet the tortured polyphony held a tight grip on the struggles central to Brahms’s voice.

The stern, brass-like opening of the scherzo movement was symphonic, with rock-solid octaves from Ohlsson’s massive hands. The soundscape was vast, as if the space in the hall has expanded. The last movement flowed with effortless power, yet the deliriously light-hearted F-sharp-minor section near the end constructed a dichotomy. Shimmering scales brought the work to a thunderous close.

The Six Pieces, Op.118, a collection of unrelated works of modest scale, followed. As if to form a symmetry, this was the second-to-last work published during Brahms’s lifetime, 40 years after the three sonatas were written. Here, Brahms’s roughly hewn lines have been tamed, but the emotional swells built on conflicts remain.

Ohlsson delivered the pieces like reminiscenses of the past: with much contemplation and a generous sense of time. Unhurried, the pianist brought out the suave melody that seemed to glide on top of expansive ocean waves in No.1, while the more intimate No.2, perhaps the most famous of the six, was sculpted as if to hang onto each of the precious moments. The prayer-like penultimate piece brought serenity, while the tonal ambiguity brought by extensive use of a diminished scale left questions initially that were answered by the decisive second half.

The second half began with the Three Intermezzi, Op.117. Ohlsson continued to deliver clearly defined melody, carefully balanced over cascading arpeggios in No.2, for example. it was easy to let Ohlsson do his work; the absence of gratuitous drama accompanied by a sense of tremendous confidence allowed the stories to carry the moment.

The Variations on a Theme by Handel, Op.25 was delivered with charm and wit. In the opening Aria, Ohlsson went back and forth between Baroque trills (starting with the note above) and Romantic trills, beginning on the note, a somewhat controversial topic among interpreters. Clearly, Ohlsson called it a draw, perhaps poking fun at those who argue to no end about the “correct” interpretation of a Baroque piece used as a theme for a massive collection of 25 variations and a fugue.

The strong, syncopated jabs in the first variation proclaimed neither Handel or purely Brahms, but an intriguing juxtaposition of two periods separated by 150 years. Ohlsson continued to present multiple sides in the work. The argument may be about which line to emphasize, or how to balance various elements in each of the variations. Rather than asserting that one approach is “correct” and other isn’t, Ohlsson provided a case for each, perhaps as if at a masterclass.

As the variations progressed though, particularly from the 22nd variation, with its bell-like ostinato, the witty discussions and arguments formed into a unified voice, through the thrusting variations 23 and 24, culminating in a triumphant and festive 25th variation. Ohlsson didn’t take a moment before jumping into a proclamation that was the opening of the fugue, based on the original theme. Here, the music moved like a train. Ohlsson clearly demonstrated all the compositional technique Brahms utilized to write the incomparable fugue, perhaps unequalled in the entire Romantic repertoire. The radiant section on the dominant 7th before the coda was embellished with a strong bass pedal point, to create an effect not unlike that of an organ in a resonant cathedral.

Ohlsson’s juxtaposition of Brahms’s early and late works demonstrated, as well, all the decisions that contribute to an interpretation. Another layer of juxtaposition was the encore, Chopin’s lamenting Waltz in C-Sharp Minor, Op.64, No.2, which reminded us of where he was nearly 50 years ago.