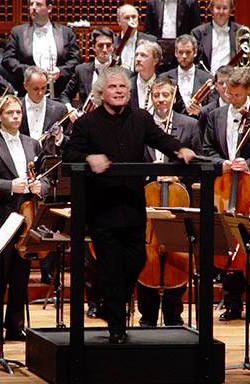

Tuesday was a busy, significant day in the world of music travel. San Francisco Symphony musicians completed their grand Asia tour, and made ready to fly back from Tokyo. Their home, Davies Symphony Hall, served as the last stop for the Berlin Philharmonic, concluding their tour of North America with concerts on that day and Wednesday. Reports speak of a great reception for the SFS concerts in Asia, and there have been ecstatic responses to the Berlin from New York to Toronto to Southern California. Still, nothing can approach the actual experience of these events, including Simon Rattle’s direction of the Philharmonic, playing at its best to a packed hall.

Boulezian Delicacy

The concerts, especially of Boulez’s brief Éclat and Mahler’s sprawling Symphony No. 7 on Tuesday, represented a ... no, the high point of my concert experience with both the works and the Philharmonic. Their performances were overwhelming with their clarity, superb articulation, and downright perfection.

Fifteen musicians are featured in Boulez’s eight-minute work from 1965, whose title translates to “fragment.” With the accent on the different reverberation times of the instruments, it requires virtuoso direction and performance — which were realized with bravura, each sound heard individually and yet within the harmonic whole.

Overwhelming Mahler Maximalism

Following the cool-and-cold chamber-music intimacy came the huge, ferocious tsunami of the 1908 Mahler Seventh, an all-involving journey, whose outsized first movement — Allegro risoluto ma non troppo — was the breathtaking peak experience of the orchestra’s two-day stand.

The entire Philharmonic, squeezed onto the Davies Hall stage, provided a dazzling sound for the work’s 80 minutes. The brilliant brass section’s roof-shaking blocks of sound in the opening and closing movements bracketed the three inside movements’ ravishing “Night Music,” the latter including miniature lyrical solos by concertmaster and Crowden School graduate Noah Bendix-Balgley in the Scherzo, which the composer asked to be played “like a shadow.”

Through the fourth movement’s wall of sound, guitar and mandolin solos could be heard clearly, the latter revealing the source of inspiration for Prokofiev’s Romeo and Juliet.

No matter how many times I hear this symphony, I still cannot warm to the boisterous, closing Rondo-Finale, but it was impossible not to appreciate Rattle’s mastery of the abrupt tempo changes, the passionate involvement of the strings, the clarity of woodwinds, and once again the brass, leading a celebration dwarfing even Respighi’s excesses.

After, and Before, Mahler

On Wednesday, Rattle’s bold, imaginative programming brought together three still-challenging figures of the Second Viennese School of the early 20th century in what the conductor calls “Mahler’s 11th Symphony.” (Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven were the leading lights of the First Viennese School, a designation seldom used.)

The newfangled suite consists of Arnold Schoenberg’s Five Pieces for Orchestra, Anton Webern’s Six Pieces for Large Orchestra, and Alban Berg’s Three Pieces for Orchestra. Expanding beyond tonality, but before full-scale twelve-tone composition, these works range from easily understandable lyricism to a musical language that still makes a majority of listeners feel as if in a foreign country without a clue. To the great credit of the precision and brilliance of the performance, the audience listened with rapt attention — not even engaging in the coughing bouts that interfered with the Brahms symphony that followed — and gave Rattle and the orchestra warm applause at the conclusion of the nearly hour-long musicological exploration.

In a reverse chronological order — which somehow made good sense — after the all-20th-century repertory, Brahms’ 1877 Second Symphony closed the Philharmonic’s San Francisco visit. Before achieving its usual splendor, the orchestra seemed at first — during the beginning of the first movement especially — to lack clarity and authority, certainly off compared with the previous night’s Boulez-Mahler precision.

Soon, however, the Berlin sound prevailed, low strings and woodwinds sang out with passion and conviction, and Mahlerian exclamations interrupting poignant passages. By the time the storm of the closing Allegro suppressed coughs, along with memories of whatever weakness might have been at the beginning, the evening and the tour closed in glory, the audience erupting in a sincere and well-deserved standing ovation.