By drilling scales and common patterns every day and in every key, musicians train their whole lives to play tonal music. Such hard-earned muscle memory is of limited help for 12-tone music. This didn’t deter famed pianist Emanuel Ax on Friday evening at Davies Hall. He dominated in two concertos: One by Mozart and another, dodecaphonic one by Schoenberg. With Michael Tilson Thomas leading the San Francisco Symphony, two additional orchestra-only pieces rounded out the program.

Beethoven struggled to write his only opera, Fidelio, and he rewrote its overture four times. Famous for its offstage trumpet, the sweeping and dramatic Leonore Overture No. 3 illustrates Beethoven’s so-called “middle period” and “heroic” style. Like the operatic plot that involves a loving wife disguising herself as a man to save her husband from death in a political prison, this overture’s music travels per aspera ad astra (through difficulty to the stars). Some transitional string passagework sounded slightly squirrelly. Listening was a little like watching an Olympic skier race alarmingly near the verge of losing control. Ultimately, though, everything held together, and Beethoven’s piece was an exciting start to the evening.

Beethoven’s Leonore exposes the winds, especially a solo flute. In Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 14, by contrast, only oboes and horns joined the strings. The juxtaposition threw the concerto’s uncommonly reduced orchestration into sharp relief. In Ax’s hands — and with the apparent ease of a dancer whose feet seem merely to skim the floor — the first movement’s melodies were clear, crisp, and graceful. This delicate elegance continued in the subdued slow movement. The finale felt restrained in terms of both dynamics and tempo, as though the whole ensemble were too mature to run and yell with childlike abandon. It was a delightful, tasteful end to the first half.

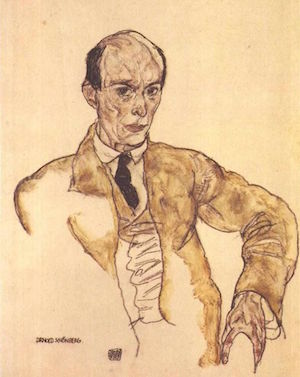

Immediately after intermission, Schoenberg’s Op. 42 Piano Concerto (1942) seemed strategically placed: It was not before the break, lest any scared-off listeners should fail to return, and the task of closing the entire program was reserved for a more time-tested crowd-pleaser.

Before the piece began, MTT tried to explain that Schoenberg’s piece was far from a radical break with tradition. Convincingly, he compared the solo piano’s opening melody, which he described as a “sonata/minuet/nocturne,” to a tonal and dreamy chamber piece. He was trying to emphasize the melody’s classically balanced phrasing and its Romantic, rhapsodic mood.

Schoenberg’s 20-minute work does indeed use 20th-century, 12-tone technique. But it also references traditional musical forms as well as 19th-century textures and temperaments. Written in 1942 while the composer was living in Los Angeles as an Austrian exile, the manuscript (but not the published version) includes programmatic inscriptions above each of the work’s four sections such as “hatred broke out” and “but life goes on” that could be read autobiographically. It was originally commissioned by Oscar Levant and, especially with Ax at the helm, some sections seem suffused with Levant’s wit.

Like the first movement of the Mozart, the first section was in triple meter. Unlike the previous concerto, though, Ax did not play the Schoenberg from memory. Given its complexity — which the frequency of the page turns actually helped to convey — you can hardly begrudge him for it.

The inner sections were a Scherzo and a plaintive Adagio, in that order. The Scherzo complicated melodic ideas from the first. Ax dazzled in the elegiac Adagio, particularly in its two cadenzas. While his lucid technique was on display throughout both pieces, this section especially showcased his wide-ranging expressivity.

As it turned out, the audience appreciated the Schoenberg even more than the Mozart. Even so, one more piece remained on the menu: Strauss’s fantastically capricious tone poem, Till Eulenspiegels lustige Streiche (Till Eulenspiegel’s Merry Pranks). Setting up the stage for this work’s heavy orchestration took a few minutes, but it was worth the wait. The swaggering, episodic music fittingly portrayed the mythical/historical prankster who inspired it.

This diverse program ranged from playful to cerebral, from classical to modern. Without difficulty and with consistent lucidity, Ax easily ran its daunting gamut.