The four canonical versions of Jesus’ Passion come at the story from different perspectives, opening as many questions as they answer. And while some oratorio settings have tried to elaborate the spiritual meanings of the passion story, composer John Adams and his theater collaborator Peter Sellars have intentionally decentered theirs. In The Gospel According to the Other Mary, Adams and Sellars amplify contrasts and make room for dozens of nonbiblical voices ranging from Hildegard of Bingen to Dorothy Day. The result is a work that sends its spirit through time in a dizzying spiral of simultaneous meanings and oppositions.

At Davies Hall this weekend, the San Francisco Symphony performed a semistaged version of their massive and ambitious collaboration — a two-act “Passion Oratorio” told from the perspective of Mary Magdalene and her siblings, Martha and Lazarus. Chiefly by blurring biblical and secular texts, The Gospel self-consciously slips between narrating the events culminating with Jesus’ death and alluding to numerous other moments in history.

The combination of materials is reminiscent of El Niño, the duo’s nativity oratorio. The Gospel’s second act, for example, opened with a blaze of strobe lights (from designer Seth Reiser) and militant police, who awoke Mary and Martha by banging on their door. Jesus was arrested, but so were Mexican women protesting for social justice in the era of César Chávez.

Jesus himself was conspicuously absent as a specific singer in this work. Instead, his part was split between the Symphony Chorus, a trio of marvelously beatific countertenors — Daniel Bubeck, Brian Cummings, and Nathan Medley — and Lazarus. At times, the splintering made Jesus seem somehow above or beyond the realm of worldly representation; at others, it befuddled the spiritual and visceral realms. In the first act, for instance, the Chorus conjured the presence of Jesus while Mary recounted not only washing his feet but also women getting back at their fathers by “wrecking their bodies on other men.”

The absence of a literal Jesus sharpened Adams’ intended focus on “women fighting for self-realization.” Adams regards Mary as an archetype of a damaged, possibly abused, self-loathing woman who is nevertheless “fanatically intent upon finding enlightenment.”

Mezzo-soprano Kelley O’Connor, the vocalist for whom Adams originally wrote the role, played Mary. A starkly simple, red cowl-neck top and humble A-line skirt, designed by Christine Cook, sharply contrasted with the fierce sophistication of O’Connor’s voice. Its depth and complexity intensely interpreted the volatility of the Mary Magdalene that Adams had envisioned. In a powerful, first-act aria, Mary desperately beseeched Martha and Jesus not to touch her left arm, which she seemingly self-injured in a suicide attempt. Tenuously moving between pain and ecstasy, the number also conveyed how Mary loves Jesus to her (surprisingly corporeal) farthest limits: “to the trembling tips of my fingers, the vibrating ends of my hair.”

If the imagery of Mary Magdalene loving Jesus in physical terms should fail to raise eyebrows, the idea of an older white man writing music about the self-realization of women might. But in The Gospel, women are hardly monolithic. In contrast to Mary’s hypersensitivity, Martha is staid and practical. Smartly counterpoising O’Connor was Tamara Mumford, another consummate mezzo-soprano. Her character vied with Lazarus (whom Jesus raised from the dead in the first act) for the most gorgeous vocal lines in the work. Performed by the imposing tenor Jay Hunter Morris, the emotive Passover-meal aria with which Lazarus closed the first act, “How is this night different,” was especially stunning.

Underlying all vocal elements was a broadly sweeping orchestral score that might amount to the richest and most diverse writing of Adams’ career to date. At Lazarus’ burial, for example, a majestic brass chorale resounded. The orchestra also terrifyingly depicted Golgotha, without any visual representation of Jesus or a cross.

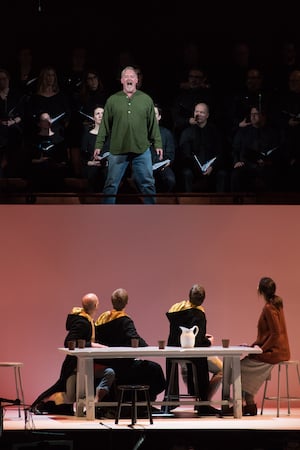

Grant Gershon made his San Francisco Symphony debut by skillfully conducting the production’s intimidating three tiers of musicians: the symphony on stage, the minimally staged soloists on an elevated platform, and the Symphony Chorus in the choral terrace. Director Elkhanah Pulitzer fruitfully oversaw this tripartite layout.

The Latin word from which our modern “Passion” derives means both “suffering” and “enduring.” Fulfilling both meanings, The Gospel encourages suffering and hope from the biblical story to reverberate — scintillatingly and bewilderingly — across 2,000 years of human history. By blurring oppositions including past/present and sacred/secular, this weekend’s Gospel was a Passion for a world beyond time.