Twice, in Sunday’s all-star-name evening of Beethoven string trio music at Davies Symphony Hall, the center held.

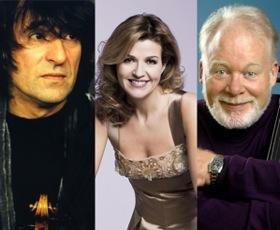

It happened first, in a buoyantly comic mode, during the middle-movement Adagio-Scherzo of the Serenade in D Major for String Trio, Op. 8. That’s when cellist Lynn Harrell played papa bear to his two frisky cubs, violinist Anne-Sophie Mutter and violist Yuri Bashmet. With a single, sternly voiced low note, which he was obliged to repeat several times, Harrell rebuked Mutter’s and Bashmet’s antic outbursts. Mission accomplished, he triumphantly flipped the page of his score. The visual “harumph” earned a laugh. Then humor yielded to quiet ravishment, as the movement wound on in a yearning, quizzical mood. The result was a musically eventful and absorbing transformation.

After intermission of this Great Performers Series concert, the Mutter-Bashmet-Harrell Trio took up Beethoven’s first string trio, the discursive E-flat Major, Op. 3. It was there, in the choice Adagio poised between two brisk and angular minuets, that the players found their other moment of great accord. Led by Harrell’s gently probing eloquence, the ensemble played with a sense of shared wonder here. Dynamics merged. Harmonies unspooled gracefully. Dissonances lingered affectingly. All three musicians seemed to listen and respond to each other in a common cause.

It was that very virtue, unfortunately, that largely went missing Sunday. Instead of witnessing a meeting of fine musical minds, the Davies audience often heard three superb players going their own ways. Mutuality was a fleeting component. Imbalance prevailed, with Mutter dominating, to a fault.

Right from the program’s rough start, when Mutter’s intonation problems plagued the opening Allegro of the String Trio in C Minor, Op. 9, No. 3, this “Evening of Beethoven” had the feel of a soloist strutting her virtuoso stuff. Harrell and especially Bashmet got lost in the glare. That was so much the case for the Russian violist that it wasn’t until the sixth movement of the Serenade, a theme-and variations turn, that Bashmet’s warm and mellow tone registered. Listeners’ heads turned to one another in approving surprise.

Reining in the Star Power

Enticing as they may be, big-name chamber programs in a large hall like Davies hold inherent risks. The impulse must be strong for a major soloist like Mutter to take the big stage and stamp it with her own distinctive personality, as she’s been doing for many years. That’s the presumptive challenge of playing chamber music in a venue that’s anything but intimate. Overstatement must be hard to resist. Eye contact and a communal body language — that subtle but almost palpable tissue that binds chamber players together — weren’t much in evidence. Even the stage furniture reinforced the lack of unity; Mutter perched on a piano stool, while Bashmet and Harrell were seated in conventional backed chairs.

The program itself addressed some of the intrinsic liabilities. Two of the three pieces represented Beethoven’s larger gestures in the string trio form he adopted (and abandoned) early. His last string trio, which was performed first on Sunday, dates to 1798. Both the seven-movement Serenade and the six-movement Opus 3 Trio, the latter apparently inspired by Mozart’s masterfully sublime Divertimento for String Trio, K. 563, are form-stretching works.

The Mutter-Bashmet-Harrell team had assorted gleaming moments in both of them. The Serenade opened with a spirited, sunlit march. The Adagio that followed melted together tenderly in spots. An easy but deftly turned musical joke nearly brought the Allegretto alla polacca to a premature dead halt, like a runner out of gas. The Opus 3 is a gassier enterprise, lengthy without enough to say. But again the players found their ways to shine: in a bright opening Allegro and in the driving syncopations of the first minuet.

Still, the misgivings that arose early in the evening never fully abated. Whether she was limber and liquid, or sometimes piercing and less than tone-pure, Mutter claimed too much musical ground. Harrell, the most seasoned chamber player of the three, did his best to level the ground. But this match, played on this big field, was an uneven one before it ever started.