What do Henry Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (premiere 1689) and Manuel de Falla’s La Vida Breve (premiere 1913) have in common? Besides their relative brevity, and female protagonists who die from forsaken love, scarcely a note. It takes a giant leap of faith to dare bridge, in a single evening, the musical and psychic divide between these operas of the English baroque and early 20th-century Spain.

Enter West Bay Opera. Under the tutelage of José Luis Moscovich, the small company with the large following has already successfully mounted a number of behemoths, including Verdi’s Macbeth and Puccini’s Turandot. If those implausible endeavors flew on the small stage of Palo Alto’s Lucie Stern Auditorium, why hesitate to mate such strange, albeit far more intimate operatic bedfellows?

Certainly Moscovich found in Cathleen Candia a remarkably versatile mezzo-soprano who easily encompassed both female leads. For the high-lying role of Falla’s scorned gypsy girl, Salud, Candia adopted a touching, soprano-like sound that easily rose to a B flat. For Purcell’s lower-scored lovelorn Queen of Carthage, Dido, she emitted tones rounder, fuller, and rewardingly richer. With Abra Berman’s distinctly different period-apt costumes further altering her appearance, it became difficult to believe that both roles were sung by the same beautifully voiced woman.

But an exceptionally strong lead is not enough to carry an evening. Despite a few other fine singers, there were so many stumbles along the way that La Vida Breve’s barely plausible libretto turned out the least of the company’s worries.

Saving the Best for Last

Gripping the playing wasn’t, but it certainly made a stronger case for the opera than WBO’s enactment of Carlos Fernández-Shaw’s libretto. There was little in tenor Pedro Betancourt’s portrayal of the double-timing Paco, or the singing and acting of any of the other principals, to justify Salud’s sudden death. Despite some fine singing from tenor James Stahlman (the unseen voice of the forge), mezzo Carla López-Speziale (the Grandmother), and bass Carlos Aguilar (Uncle Salvador), Ragnar Conde’s limp direction further enforced the impression that La Vida Breve deserves to be remembered most for its orchestral writing

The Deadly Dido

Almost nothing in the Purcell, save for Candia’s singing, worked. Concertmaster Kristina Anderson was hardly the only orchestra member to produce poorly pitched, sour tones, but the disaster of her first phrases was only reinforced by a host of subsequent approximations from other string players. One can only hope that these frequent mishaps were due to the orchestra’s intentionally lower pitch.

During the dismal overture, a half curtain rose on a beguilingly lit, blue-tinted scene whose silver sparkles and semi-diaphanous costumes bespoke a Middle Eastern harem of bellydancers. This, it turned out, was our first look at the Sorceress (Carla López-Speziale) and her two witches (Kristen Choi and Alexandra Mena). Not only were the spectacle and choreography totally incongruous with the elegance of Purcell’s writing, but the Sorceress’s subsequent hip wiggling and near-constant waving of her arms created such a disconnect as to induce a state of disbelief.

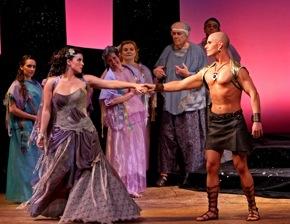

After the opening scene of consolation, during which the thin sounds of soprano Shawnette Sulker (Belinda) offered little solace, in strode straight-backed, handsome baritone Zachary Gordin. Displaying ample flesh, with only a short black leather skirt, high-strung sandals, and scanty vest covering his exceptionally buffed, alluring physique, Gordin proceeded to pose rather than act. Instead of the evenly produced natural voice that he summoned forth for the flamenco singer in La Vida Breve, Gordin displayed a sometimes gruff, graceless instrument with a shallow bottom, booming middle, and pushed top. As my Purcell-loving companion whispered to me after the performance, it seemed as though he was relying on forced volume to portray emotion.

WBO’s volunteer chorus, which really outdid itself in Turandot, seemed woefully under-rehearsed and over-parted. The men, who had only a few bad patches in the Falla, were at a loss for pitch far too often. Lighting Designer Robert Ted Anderson seemed intent on compensating for musical inadequacies by showing how many different colors he could bring to the backdrop. Blue, green, red, magenta, purple, and others, sometimes in rapid succession, added to the ridiculousness of it all.

A complete inconsistency of accents, verging from pseudo-English to nondescript, only reinforced the impression that neither Anderson, set designer Jean-François Revon, director Conde, or conductor Moscovich had stepped back long enough to establish a unifying vision for the production. Given those three misplaced bellydancers, who kept waving their arms even as Dido raised a knife to her breast, Aeneas’ voyage was reduced to a carnival cruise.