The Gold Rush was the film, as its creator and star Charlie Chaplin put it, “that I want to be remembered by.” While City Lights, Modern Times and The Great Dictator offer worthy competition, the 1925 classic about the tramp-to-riches misadventures of a Klondike prospector may well have fulfilled Chaplin’s wishes. The movie’s single most famous scene, the boiling and eating of a boot by two starving fortune hunters in a snowbound Klondike cabin, is enough on its own to seal The Gold Rush into even the most casual viewer’s memory vault. This could be the most widely-known film of the silent era.

What many moviegoers may not know is that the director took pains to make sure that his silent films were not, in fact, silent. In addition to The Gold Rush, Chaplin composed and recorded scores for a number of his own films. That was one of the drawing cards of the San Francisco Film Festival’s Charlie Chaplin Centennial Celebration at the Castro Theatre.

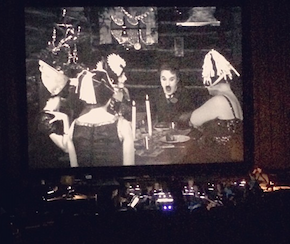

In front of an enthusiastic packed house, Timothy Brock conducted the San Francisco Chamber Orchestra in live accompaniment to the film. Earlier in the day, Brock led that same ensemble in Chaplin’s score for a screening of The Kid. Pianist Jon Mirsalis opened the day-long bill with his accompaniment of three Chaplin shorts.

A little backstory about The Gold Rush music provides some context. At its original release, the film had a score compiled by Carli Elinor and Chaplin. A 1942 re-release, with some substantial reorganization of scenes, featured a fuller Chaplin score and voice-over. A 1993 reconstruction of the film restored the silent original, with print intertitles. That was the version shown at the Castro. Brock reconstructed an aptly coordinated score. Right down to the perfectly timed drum beat rifle shots and a swirling string-and-timpani snowstorm, music and film were gracefully conjoined.

Full of quotations and appropriations — from Tchaikovsky, Brahms, Rimsky-Korsakov, Comin’ thro the Rye, Auld Lang Syne and more — Chaplin’s Gold Rush music is not a work of striking originality, even by the serve-the-medium standards of most film scores. But as a cue the creator’s complex sensibility, it provided some fresh and even startling insights.

First there’s the alert attention to detail, the deft tonal switches from moment to moment and scene to scene. That’s apparent right from the start, when the pseudo-Wagnerian gravity of miners plodding through the snow segues smoothly into a jaunty burlesque riff as Chaplin’s Lone Prospector, twirling cane in hand, teeters along an icy cliff. The music darkens ominously when a bear emerges from a cave to follow the unsuspecting hero, then quickly brightens again when the bear and man take different paths.

Niceties like that are sprinkled throughout the score. The dog first seen under a bed gets a fleeting Puccini-esque surge of affection when he comes to Chaplin’s attention. It’s a funny but telling bit of musical character development, a preview of the romantic attachment the hero will form to the puppy-faced beauty Georgia (Georgia Hale) later on. Some of Chaplin’s choices seem puzzling but provocative, upending conventional readings of a scene. In the famous bit in which Chaplin and Mack Swain, as Big Jim McKay, are about to perish in a cabin clinging precariously to a precipice, Rimsky-Korsakov’s The Flight of the Bumblebee takes off. The sense of emergency levitates into something purely buoyant and balletic. Survival becomes an insect dance.

The San Francisco Chamber Orchestra sounded nimble and responsive if a little thin and scratchy, especially in the string section, from a seat in the balcony. The atmosphere of something old and a little worn was sometimes all too accurately conveyed. The woodwinds, who were kept busy in bustling narrative commentary, fared better. The percussion, down to every last rifle shot and wood block punctuation, were on the mark.

Chaplin remains eternally young 100 years after his Little Tramp character first appeared. And now, increasingly, we keep learning about his musical side. On April 12, the San Francisco Symphony will reprise its gratifying 2006 performance of City Lights, with Chaplin starring onscreen and in the pit. As writer, director, star, composer and restless rethinker of his films, this ultimate auteur simply can’t be captured by any single silent image.