The provincial capital of Bến Tre, made famous during the Vietnam War, is far from the peaceful town of Napa, but apparently they share something in common, according to a prominent local resident. Bến Tre was where American officers — quoted in a 1968 Associated Press report — said it was bombed because "it became necessary to destroy the town to save it."

Closer to home and the present time, and with far less deadly consequences, the jewel box of the Napa Valley Opera House is about to undergo major surgery, in order — say its leading board members, according to L. Pierce Carson's Napa Valley Register article — to save it from becoming a museum ... or worse.

Board chair Bob Almeida announced on Friday that the financially troubled facility is doomed without action because "we cannot maintain the present business model."

The proposed solution: subleasing the building to City Winery of New York and Chicago, and turning the first-floor cafe into a restaurant, replacing auditorium seats with cocktail tables and chairs.

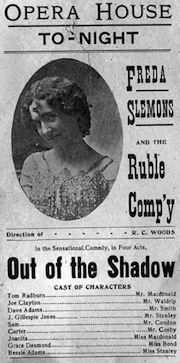

The Opera House first opened in 1880, closed eight years after being damaged in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and losing audiences with the demise of vaudeville. A community effort, which began in the 1970s, saved the building from being torn down and raised funds for its restoration. The renovated Opera House reopened in 2003. Earlier this year, the building hosted its first opera proper in its 133-year history.

Almeida, according to the Register, estimates the proposed physical and business-model changes could bring 300 shows annually to facility, "bringing 67,000 patrons to downtown Napa ... a boon to downtown business."

Asked about the proposal, Michael Savage told SFCV: "The supper club people are counting on tourists, but I think they're dreaming — meanwhile our little jewel of a theater will have been permanently eviscerated."

Savage has a great deal at stake: responsible for the 1996-1997 reconstruction of the War Memorial Opera House, of Yountville's Lincoln Theater, and of the Napa Opera House itself a decade ago, Savage was also executive director of the Napa Valley Opera House from 2000 to 2004. Last week he wrote to Almeida and the board:

If you're losing money on every show it doesn't make sense to increase the number of shows. There are no economies of scale in this, rather the reverse since the more shows you do the lower the average attendance. You're likely to worsen the economics.Fundraising is key. No not-for-profit theatre can expect to cover more than 40-50% of its expenses from ticket sales. My solution would be to determine the amount of fundraising that your board and key volunteers with the help of the development director can achieve in a given year. Then reduce the number of shows to the point where the fundraising total balances the budget.

This plan would lessen the stress on the opera house's overstretched staff, enable the quality of the shows to be maintained or raised, and permit us to retain the Opera House in its present beautiful form, which so many in the community dedicated themselves to achieving.

There is no particular magic in putting on shows every night. People will appreciate the theatre more if the shows are smaller in number but high in quality. For example, San Francisco Opera puts on only nine shows a year for a total of 73 performances. Lyric Opera of Chicago, probably the most consistently successful opera company in the country, has always limited itself to eight shows a year (66 opera performances). Neither company has felt its fundraising ability (which at SF Opera totaled $35 million last year) constrained by the fact that they are dark 80% of the year.

About the plan to reconfigure the house, this is what Savage had to say:

Last night, the acoustics of the show which preceded the meeting, were spoiled by the heavy drapery behind the performers. This just deadens the sound, failing to make the best of the theatre's warm acoustics which were designed by world-renowned acoustician Larry Kirkegaard.Removing the rake from the theater floor would of course destroy Mr. Kirkegaard's acoustic plan, a price the board evidently considered worthwhile paying. Mr. Kirkegaard's projects include Boston Conservatory of Music, Royal Festival Hall London, National Concert Hall Dublin, Philadelphia Academy of Music, Davies Symphony Hall makeover San Francisco, Carnegie Hall Studio Towers renovation, Green Music Center, Sonoma County and dozens of others worldwide. I wonder how many of them would even remotely consider ripping out Mr. Kirkegaard's design to replace it with a supper bar?

By the weekend, however, Savage wrote that Almeida has advised him that "this deal with a third party from New York is a fait accompli," and he appeared to give up the fight. Executive Director Peter Williams' response to a request for comment Saturday night was that "the Register article pretty much covered it; at this point, there is nothing more to add," but other had plenty to say.

James Keolker, former vice president of the Napa Valley Opera House Board, told SFCV:

I feel the current members are about to sell out their stewardship of the wonderful old theater. It would have cost a great deal less to simply tear down this 1879 structure on the banks of Napa Creek and build an up-to-date performance center. But the Board at that time felt unanimously to reconstruct this fine old building that had once housed the performances of John Philip Sousa, Jack London, Luisa Tetrazzini, and a score of traveling groups.In fact, the theatre opened with a pirated edition of Gilbert and Sullivan's HMS Pinafore that was one of the reasons they traveled to the states not long after to establish their US copyright. So, this is a very historic place.

But the current Board would rather "kill" the patient in order to save him: That is, destroy the opera house for a cabaret in order to "save" it. As most folks in the Bay area now know, Napa has a glut of high-end restaurants and two barely-sucessful cabarets. But why this Board feels their model will succeed of establishing yet another restaurant, and demolishing the theatre for a cabaret where others are failing, makes little sense and defies logic.

Another Napa arts executive is equally dismayed. Composer Richard Aldag, a Yountville resident and former general director of the Napa Valley Symphony (see this week's Music News for a related item), says:

I'm not sure what I think about the new model. It is sad, yet at the same time there are only 130,000 people in Napa County and approximately 50% of them are vineyard/agricultural workers.From my perspective, there were too many people who wanted the glory of funding capital projects. Everyone wants his/her name on a building. Yet, the community is unable to support the programming once the facility is up and running — plus, every winery wants to get into "show business" to draw people to their own properties.

Just look what happened to Bottle Rock. I believe that they still owe over $2.5 million after their first festival. Big ideas, bad planning, incompetence — "build and they will come" — NOT! It's the Wild West, individualism without regard to community.

Returning to the Register account:

With operations in both New York and Chicago, City Winery books mostly acoustic talent in the pop, folk, jazz and world music veins, similar to what the Opera House offers today. It also promotes wine as a preferred beverage to patrons in both its restaurants and showrooms.With 10 years of experience behind them, members of the Opera House board concluded "the economics of a standalone theater are unsustainable," Almeida told the assembly. "Ask George Altamura what kind of check he writes to keep the Uptown (Theater) open. This is the best path forward to preserve the Opera House for future generations."