Last Wednesday's San Francisco Symphony concert presented a strong contrast in luster. The second half had it; the first lacked it.

First, there was a fairly opaque opening number, Oliver Knussen's Symphony No. 3; second, there was Deborah Voigt's voice, which seemed to have trouble warming up to Richard Strauss' Four Last Songs; third, there was Michael Tilson Thomas on automatic pilot, doing little to contour the music. But after intermission everyone came to life for Samuel Barber's dramatic Andromache's Farewell and Beethoven's Fourth Symphony. The result was like a come-from-behind victory by a home team after a half-time pep talk.

Knussen's is a well-orchestrated symphony, larded though it is with modernisms. Having conducted its London premiere in 1979 and elsewhere (though never before in San Francisco), Tilson Thomas must be considered its champion. But why, contrary to his usual practice, did he not introduce the symphony to the audience? He remarked afterward that he just wanted listeners to concentrate on its "sounds." If they were prompted to do just that by reading Thomas May's program notes, "with one ear ... on the big picture ... and the other to the 'internal network' of relationships happening on the most detailed level," the result was unusually tepid applause. "Boring," proclaimed my seat neighbor.

Voigt was suitably impassioned, her notes and diction were spot-on, and Tilson Thomas' gestures drove the orchestra to speak eloquently of Andromache's catastrophic predicament. At the conclusion, mimicking the start of Astyanax's trajectory, he pirouetted with the final stroke of the baton to face the cheers of the audience.

A fine account of Beethoven's B-flat symphony closed the evening, with MTT continuing his use of interesting gestures. A sparklingly conducted first movement; a swinging, treadmill-like motion in parts of the third movement; and joyous swaying in the finale all contributed, along with the Barber, to the concert rescue.

What Marin Alsop introduced years ago at the Cabrillo Music Festival as a "talk back" session after the concert, MTT packaged as an "Off the Podium" period during which he answered and philosophized on eight questions from audience members. Those who didn't already know discovered that he hates Wagner's German in the Ring librettos and that, among conductorial types such as "major general" or "high priest," he likens himself to a stage director who gives actor-musicians the confidence to do their thing. "My role is like the guy in the circus who catches people from the trapeze," he proclaimed.

Too bad that, to be true to Barber's and Euripides' conception, trapeze-guard MTT had to let Astyanax fall. When it came to war, the Trojans were the have-nots.

Voigt was suitably impassioned, her notes and diction were spot-on, and Tilson Thomas' gestures drove the orchestra to speak eloquently of Andromache's catastrophic predicament. At the conclusion, mimicking the start of Astyanax's trajectory, he pirouetted with the final stroke of the baton to face the cheers of the audience.

A fine account of Beethoven's B-flat symphony closed the evening, with MTT continuing his use of interesting gestures. A sparklingly conducted first movement; a swinging, treadmill-like motion in parts of the third movement; and joyous swaying in the finale all contributed, along with the Barber, to the concert rescue.

What Marin Alsop introduced years ago at the Cabrillo Music Festival as a "talk back" session after the concert, MTT packaged as an "Off the Podium" period during which he answered and philosophized on eight questions from audience members. Those who didn't already know discovered that he hates Wagner's German in the Ring librettos and that, among conductorial types such as "major general" or "high priest," he likens himself to a stage director who gives actor-musicians the confidence to do their thing. "My role is like the guy in the circus who catches people from the trapeze," he proclaimed.

Too bad that, to be true to Barber's and Euripides' conception, trapeze-guard MTT had to let Astyanax fall. When it came to war, the Trojans were the have-nots.

No Art for Art's Sake

Yet this music did employ a masterful array of sounds and considerable inner drama. Partly because Knussen prides himself on concision — "I prefer to be bewitched of a few minutes than hypnotized for an hour" — there was little musically for a virgin audience immediately to latch on to during his symphony's complex 15-minute span. May's notes did mention that the work was inspired by "the final unhappy hours" of Shakespeare's Ophelia. However, if any music is to reflect Ophelia's death to an audience, it must contend with painter John Everett Millais' ravishingly floating portrait, where "There is a willow grows aslant a brook." The only floating I could imagine from Knussen's take, however, was more that of Marie's body after Wozzeck has done his murderous business in the pond. Fortunately for my misdirected image, Knussen used clever descending bass notes at the end to sink the remains decently out of sight. If Knussen had shorn his symphony of programmatic references, and conductors had allowed audiences explicated, multiple hearings of the sounds themselves in the abstract, the work would have stood more of a chance of staying above water. Unlike the Knussen symphony, Strauss' swan-song masterpiece is a familiar program item. Often the entire set of four songs is taken at dirge-plodding pace, so I was initially pleased that Tilson Thomas began "Spring" in a lively manner worthy of its title. But as the music progressed, the interpretation became more pro forma, and I began to long for any one of the many fine recordings in my collection. Voigt's voice was relatively dry and unexpressive in the first two songs, but began to hit its stride toward the end — yet Tilson Thomas seemed to do little to help.A Fling With Music and Trapeze

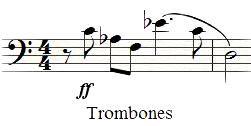

After intermission, a different MTT emerged, the one who has done great things with Mahler, and he and Voigt presented a splendid scena of Andromache's goodbye to her and Hector's son Astyanax during the sack of Troy. Shamefully, this was the first performance by the Symphony of this great 1963 work. Its powerful leitmotiv, cyclically manipulated along the lines of Barber's three essays for orchestra, tragically projects Andromache's intention, with its last three down-dropping notes, to fling the child from the walls to save him from a worse death at the hands of the Greeks. Voigt was suitably impassioned, her notes and diction were spot-on, and Tilson Thomas' gestures drove the orchestra to speak eloquently of Andromache's catastrophic predicament. At the conclusion, mimicking the start of Astyanax's trajectory, he pirouetted with the final stroke of the baton to face the cheers of the audience.

A fine account of Beethoven's B-flat symphony closed the evening, with MTT continuing his use of interesting gestures. A sparklingly conducted first movement; a swinging, treadmill-like motion in parts of the third movement; and joyous swaying in the finale all contributed, along with the Barber, to the concert rescue.

What Marin Alsop introduced years ago at the Cabrillo Music Festival as a "talk back" session after the concert, MTT packaged as an "Off the Podium" period during which he answered and philosophized on eight questions from audience members. Those who didn't already know discovered that he hates Wagner's German in the Ring librettos and that, among conductorial types such as "major general" or "high priest," he likens himself to a stage director who gives actor-musicians the confidence to do their thing. "My role is like the guy in the circus who catches people from the trapeze," he proclaimed.

Too bad that, to be true to Barber's and Euripides' conception, trapeze-guard MTT had to let Astyanax fall. When it came to war, the Trojans were the have-nots.

Voigt was suitably impassioned, her notes and diction were spot-on, and Tilson Thomas' gestures drove the orchestra to speak eloquently of Andromache's catastrophic predicament. At the conclusion, mimicking the start of Astyanax's trajectory, he pirouetted with the final stroke of the baton to face the cheers of the audience.

A fine account of Beethoven's B-flat symphony closed the evening, with MTT continuing his use of interesting gestures. A sparklingly conducted first movement; a swinging, treadmill-like motion in parts of the third movement; and joyous swaying in the finale all contributed, along with the Barber, to the concert rescue.

What Marin Alsop introduced years ago at the Cabrillo Music Festival as a "talk back" session after the concert, MTT packaged as an "Off the Podium" period during which he answered and philosophized on eight questions from audience members. Those who didn't already know discovered that he hates Wagner's German in the Ring librettos and that, among conductorial types such as "major general" or "high priest," he likens himself to a stage director who gives actor-musicians the confidence to do their thing. "My role is like the guy in the circus who catches people from the trapeze," he proclaimed.

Too bad that, to be true to Barber's and Euripides' conception, trapeze-guard MTT had to let Astyanax fall. When it came to war, the Trojans were the have-nots.