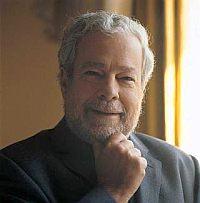

Beginning with his debut at age 5, Freire has always been a quiet, self-effacing pianist. Now, 60 years later, his physical presence is truly Zeliglike. The Brazilian artist's performances are also simple and straightforward, quite without flair or panache, but they can also dazzle with virtuosity and speak directly to the heart.

And so his recital began, with six measures of pure beauty, a sublime way of handling what is often the most difficult part of a recital: the transition from silence and expectation to music. Peak experiences at concerts often come in the middle or at the conclusion of a piece; here, the first sounds said it all.

As a last-minute substitute for the scheduled Mozart Sonata in A Major, K. 331, the program opener was Schumann's 1831 Papillons (Butterflies), Op. 2 (Numbers 1-12), a suite whose variations are based on that brief introduction Freire played so winningly, and with such certainty and warmth it brought Arthur Rubinstein to mind. With all the great performances of the evening, it was not until the second half of the performance with Debussy and a trio of encores that Freire matched the lyrical impact of the Schumann.

For the largest piece on the program — Brahms' Sonata No. 2 in F-sharp Minor, Op. 2 — different aspects of Freire's artistry emerged, especially his ability to hold together an architecturally complex, swiftly changing work of many moods and voices. Here, the pianist's narration of the sonata's story was clear and powerful.

The effortless virtuoso (and yet another reminder of Rubinstein) came to the fore in Chopin's Barcarolle in F-sharp Minor, Op. 60; Mazurka No. 26 in C-sharp Minor, Op. 41, No. 1; the Mazurka Posthume in A Minor; and — most notably and charmingly — the Scherzo No. 4 in E Major, Op. 54.

Beyond all these, and two wonderful Heitor Villa-Lobos pieces (Alma Brasileira and Danca do Indio Branco), the most memorable part of the evening came with three brief, but substantial pieces from Debussy's Preludes, Book I: No. 4 (Les Sons et les parfums tournent dans l’air du soir), No. 5 (Les Collines d’Anacapri), and No. 12 (Minstrels). Piano and pianist practically disappeared here, yielding to the music completely, and providing yet another extraordinary experience.

Back to the soulful sound of the concert's opening measures, the first encore came from the heart: "Dance of the Blessed Spirits" from Gluck's Orfeo ed Euridice (in Giovanni Sgambati's transcription, though no announcements were made), which cast one of those precious spells over the hall that the audience is reluctant to break with applause. Superb miniatures by Villa-Lobos and Federico Mompou concluded an evening to remember.

Remember that Chamber Music San Francisco's Herbst season is still only halfway through. And, how about some more Freire, namely the third movement of the Waldstein?