The symphony orchestra and the spoken rather than the singing voice are not a common combination in the concert hall. Ralph Vaughan Williams’ Sinfonia Antarctica and Aaron Copland’s Lincoln Portrait are two of the few pieces of the sort that have survived the test of time. One reason they do is that their composers let the music do most of the talking, as does Joseph Schwantner in his New Morning for the World (1982), a work honoring the words and legacy of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

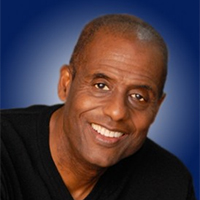

Fight as King did to end discrimination, I confess that I’m totally biased in favor of Schwantner’s piece, recordings of which I play most MLK days in order to ponder the civil rights leader’s accomplishments. Needless to say, I was very pleased to attend the second, Tuesday performance of the Marin Symphony’s “American Dream” program, which coupled New Morning with Copland’s Third Symphony. Alasdair Neale conducted; the multitalented Noah Griffin read King’s stirring words. The results in the Schwantner were excellent and powerful, but more problematic in the Copland.

At nearly a half hour in length, and based on only a few motifs, New Morning may strike some as a bit long and repetitive. And in truth it would be — on its own. But King’s words, a springboard into contemplation of the historic and ongoing struggle for racial equality and economic opportunity, give Schwantner’s music legs. To remind us of battles fought, the piece has a massive and clangorous percussion section and a jagged, upward climbing theme (similar to the bridge section of Ennio Morricone’s title tune for “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly”). Most powerfully, on top of these after the speaker intones King’s “the arm of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice,” Schwantner’s brass presents 18 times a series of three or four stepwise, ascending notes leading to choir-like dissonances and harmonic resolutions. These are reminders that there is no one victory, but many painful confrontations and resolutions to human progress.

Neale’s pacing was perfect for the gravity of this masterpiece, and the Symphony percussion section came through with a bang-up contribution. Griffin’s reading was highly informed (see his discussion on the Symphony website). I especially like the way he phrased “for all of God’s children,” and “This is our challenge — and responsibility.” Only in “it bends toward justice” did Griffin fail to take full advantage of the power of the phrase. Also, I feel the volume of his microphone could have been set a tad higher, at least for where I was sitting in Row 10. For readers wishing to celebrate next year with Schwantner’s music, I suggest the Slatkin recording with the National Symphony and Vernon Jordan narrating.

The Copland symphony, which concluded the concert after an intermission, is a good companion piece to the Schwantner. Its Fanfare for the Common Man component fits in with King’s lately less-realized dream of “privilege and property widely distributed; a dream of a land where men will not take necessities from the many to give luxuries to the few.”

Neale did well to continue the power of the first piece in the program into the second, though at times he slowed a bit too much and dissipated momentum. Copland’s use of syncopation is immensely varied and complex in the Third. Unfortunately, the timing difficulties associated with this technique became all too apparent in ragtag renditions of certain passages. The Marin Symphony brass, however, was on the mark in the Fanfare; a highly pleased audience at the conclusion gave it well-deserved accolades.