“I cannot be more specific,” he said with some frustration. “What else can I tell you? It was a great experience being in that orchestra and the people around me were a constant inspiration ….”

Yes, we said, but could you not paint a scene of what it was like in those days, a moment that comes to mind?

This was one of those times when you realize a true difference between writers and musicians in understanding the requirements of a scene: the one listening for an auditory cue; the other looking for an image.

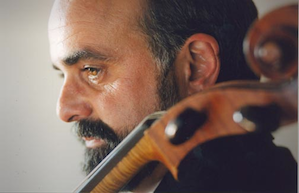

Here was Emil Miland, now 54, recovering memories of what it was like to be 15, playing in the Oakland Youth Orchestra (OYO), then under the direction of Robert Hughes. Miland was already a star and at 16 he would go on to solo at the San Francisco Symphony and, years later, solo in Carnegie Hall at the invitation of Frederica von Stade, for her farewell recital.

For the last 26 years, he’s been with the San Francisco Opera Orchestra. This weekend he’ll be playing with the Oakland Youth Orchestra as part of their 50th anniversary.

Miland’s father was a music educator in Alameda; his older sister also played the cello. Growing up in the 1960s, Miland went to hear the youth orchestra even before he joined it. Later, he would study with legendary cello teacher, Milly Rosner and also Sally Kell, then a principal with the Oakland Symphony.

A scene?” he repeated. “I still don’t understand. Ask me something else and let me think.”

Views of a Masterpiece

This weekend, Miland will be playing Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor. “Now there’s a piece that lets the cello really sing,” he said. “It also has some wonderful bravura with it.”

The piece was chosen for the program because Miland first played it at OYO. Not long afterward — in 1976 — OYO was invited to an international festival of youth orchestras in Aberdeen Scotland. That got Miland an audition for a year’s study in London. The piece he played for the audition was Elgar’s concerto — Elgar’s last major piece, written in 1919, with the stench of Passchendaele perhaps still on his mind. It got off to a disastrous start after a poorly played premiere. In 1960, Jacqueline Du Pre revived it and it’s been popular ever since.

Miland’s year in London included lessons with Du Pre’s teacher, William Pleeth.

What’s the difference between playing it now and then, we asked.

“At 16, you’re fervently hoping to dive as deep as you can and then soar as high as you can. But when you’re older you have a greater sense of how high is high and how low is low.” -Cellist Emil Miland

“I have more of a sense of it and of course there’s a sense of nostalgia. It might be easier to summon; it’s not exactly easy music, there’s a certain sadness inherent in it. A longing. Of course, at 16, you’re fervently hoping to dive as deep as you can and then soar as high as you can. But when you’re older you have a greater sense of how high is high and how low is low, and naturally you have access to a broader range of human experience. Part of being a musician is having the opportunity to use maturity. And after all, what’s the point of playing these notes over and over again unless they change as we do?”

Miland added that the sadness in the piece had resonance for him, “when you hear of all these mass shootings and battles around the world.”

“There’s one passage I like above all. It’s in the last movement, where for a while it’s as though there’s just one giant cello, and we forget our individuality and become part of this thing that is so great, and so much greater than any individual.”

An Elusive Memory

That was it. That’s was the key to the memory he was trying to find. The power of playing together. The meaning of one instrument’s voice among many. He remembered a moment from the youth orchestra.

“What I learned early on,” he began, “was what a joy it was for all of us as individuals — more a miracle than a joy I suppose — a miracle to come together as individuals and create this incredible huge sound. I remember it was Tchaikovsky’s “Pathetique” Symphony. You know that part, the waltz that starts with the cellos?”

“What’s different when you’re 54 is that you realize it really isn’t about you anymore. I have a few more years of a professional life, but now I have this real sense that these kids are the future, and when you get a glimpse of their brilliance and knowing and confidence, it makes you feel better.”—Emil Miland

He sang a few bars.

“Well, all of us playing that in a section; it was like the most fun I ever had. Really, I can’t tell you.”

He fell silent for a while.

“All those wonderful people,” he said finally. “Denis De Coteau was another. They were so encouraging and they kept us on the ball. But you always looked forward to those three hours a week. You know, I don’t envy these kids now, they have to get so focused and so soon. In a way, the youth orchestra did that for us then. Those weekly gatherings were a place to focus and a place to check in with each other and develop that sense of collegial respect you need as a musician.

“It’s so important at that age,” he added, “to have a place where you can go and apply your dreams.”

Now Emil Miland had found his perspective.

“You know, it’s been such a luxury this last month to rehearse with these kids, because first, I think the world of Michael Morgan, he’s such a terrific conductor, musician, and colleague, but also because I’ve been so inspired by these young people trying to bring something beautiful into this troubled world, where we get hit with all the bad news that’s at our fingertips.

“As for the music, I think what’s different when you’re 54 is that you realize it really isn’t about you anymore. I have a few more years of a professional life, but now I have this real sense that these kids are the future, and when you get a glimpse of their brilliance and knowing and confidence, it makes you feel better. And so, at my age I’m so grateful to have these memories, particularly of all the people that helped me, the people that just wanted us to play beautiful music and what a wonderful gift that was; but now you want to start doing that too. I would say that’s where I’m at.”

Feb. 1, 1 p.m., Rossmoor, Walnut Creek; Feb. 2, 1 p.m., San Leandro Center for the Arts. World premiere of Nathaniel Stookey’s Go; Rimsky-Korsakov’s Capriccio Espagnole, and Edward Elgar’s Cello Concerto in E Minor.