Photo by Alejandro Gomez

Things were looking a little iffy Friday night when the curtain went up on Serenade, launching Ballet San Jose’s first repertory season under new artistic director Jose Manuel Carreño. A budget shortfall had canceled the live orchestra as well as Saturday matinees for the opening of the three-program season, not an encouraging start for a new administration. In Serenade’s opening moments, the dancers looked scared and stiff; they fell a bit behind the music, and then one dancer simply fell (swiftly regaining her footing). But after five minutes, everything was beautiful at the ballet, remaining so throughout the rest of the evening.

The jitters went away as Serenade, choreographed to Tchaikovsky in 1935 by George Balanchine for the company that would become the New York City Ballet, worked its magic. You could call it a ballet about everything, or a ballet about nothing. It’s a valentine, surely, to friendship, love, devotion, and dance. It draws its power from a series of divertissements and vignettes, here nicely articulated with the speed and unison, if not always the musicality, essential to Balanchine style.

There were standout performances, particularly from principal dancers Alexsandra Meijer and Ommi Pipit-Suksun, combining fluency with emotional nuance. New principal dancer Nathan Chaney’s courtly demeanor and fine technique, honed at the Kirov Academy in Washington, D.C. and as a soloist at the Zurich Ballet, gave hints of good things to come. Company-wide, the emphasis on presenting a unified classical style via training under the American Ballet Theatre’s curriculum is making Ballet San Jose look cleaner and clearer.

This can be most helpful in a work like Finnish choreographer Jorma Elo’s Glow-Stop, which seems at times to flail meaninglessly. Giving full attention, thus full value, to the sudden, seemingly random arm movements as much as the steps somehow makes the whole thing bearable, even comprehensible.

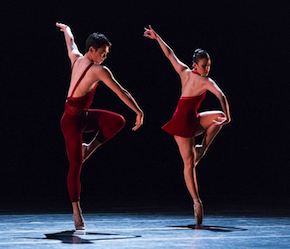

Dressed in red velvet, Glow-Stop, a company premiere, veers from Mozart in the first section to Philip Glass in the second. Elo seems determined to conceal the dancers’ faces; at times their backs are front and center, blocking full expression of emotion and vitality despite the speed and intricacy of the partnering. Glow-Stop drew committed performances from James Kopecky and Akira Takahsahi, as well as Amy Marie Briones, to name but a few.

When you’re Ballet San Jose, trying to draw community support, it’s smart as well as fun to show audiences that the company wants to have, ahem, a relationship with them. Ohad Naharin’s Minus 16 is a perfect choice. Without pandering, it makes dance and dancers approachable. Choreographically, it’s inspired. Naharin, artistic director of Israel’s Batsheva Dance Company since 1990, has set this dance on many companies (the Alvin Ailey troupe is bringing it to Cal Performances in April), and it’s different every time. Its underpinnings are Naharin’s invention, Gaga, exploring sensation and movement. The result is improvisatorial, not normal for a ballet troupe, which is just fine.

Minus 16 begins at intermission, as one man in a suit ambles onto the bare stage to a cha-cha beat, gaining speed as he captures attention with his jazzy steps, slouches, and jumps. The curtain falls, then rises on the company, in unisex black suits, white shirts, and fedoras, all seated in a semi-circle on folding chairs, kicking, puffing out their chests, waving their arms and living it up. In unison they rise, shouting in Hebrew the chorus of a traditional Passover song, verse after verse. Except, that is, for one man at the far right, who topples out of his chair and onto the floor at the end of each verse, re-sitting until the end of the next. And a man near the center who scales his folding chair, climbing faster and more daringly with each repetition.

The dancers soon shed their suits, shirts, hats, and shoes, throwing them on the floor. They’re in grey skivvies, still shouting choruses, as the chairs and the pile of clothes are taken away for the next scene, a slow, interesting, and inscrutable pas de deux. The man approaches the woman, reaching at her with clasped fists. Is he praying, begging, or preying on her? It could mean anything. He seems gentle and she seems amenable, but there’s a slightly scary quality to his moves, even as they embrace each other for the final moment.

Soon the third scene gets everyone back into their clothes, and they — uh-oh — walk down into the auditorium, each choosing a partner to take up to the stage. This is outreach writ large. Lovely, retro-cheesy music, the soundtrack for Cha-Cha De Amor, accompanies the dancing couples. The audience members’ style, or lack thereof, made the real dancers look even better, especially since everyone seemed to be having so much fun. A few songs later, the guest artists returned to their seats, except for one woman in a bright apricot dress, held oh-so-tight by her BSJ partner as they continued to dance. When he broke his clinch, she returned to her seat, accompanied by a huge follow spot and cheers that only grew warmer when Ballet San Jose boogied onward for the final curtain.