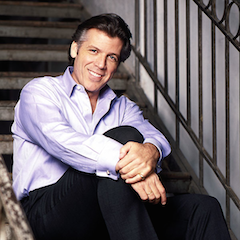

A fresh breeze blew into the San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s concert hall Monday: Thomas Hampson giving a master class to three gifted singers from the Conservatory. In town to sing Renato in the San Francisco Opera’s current Un ballo in maschera, the celebrated baritone took an untraditional tack, first with jocular, unbuttoned humor to warm up the sizeable audience (“Be sure and turn on your cell phones when you leave”). And always with encouraging and supportive admiration to the singers; “Wonderful,” “that’s fine,” “you have a great talent,” as opposed to the old-fashioned negative, picky approach.

He worked and spoke fast, giving the audience as well as his subjects a lot about singing to chew on. In fact, a major distinction of this class was that the audience could learn almost as much as the singers. One of Hampton’s main points was the importance of connecting the vowels. He kept picking on the “ee” sound, insisting that it be sung not horizontally (in the “smile” manner) but vertically, pulling it into a deeper vowel, an “oh” with which it might be linked, as in coi.

Working with the baritone Christian Pursell who was singing Sergeant Belcore’s “Come Paride vezzoso” (Donizetti’s L’elisir d’amore), Hampson lectured about the vowel-consonant relationship. Discussing the difference between singing and speaking, between cantando and parlando, he said, “When we speak, we separate vowels by consonants. With singing we bind the vowels with the consonants.”

Hampson had Pursell repeat parts of the aria, getting him to sing in broader phrases and to draw the sound upward, in the vowel-flow he was after. Hampson would drop in aphorisms: “If you don’t feel better after you sing, you’re probably on the wrong track.” “Do you breathe through your nose or your mouth?” “Both” came the correct answer, followed by the line, “The nasal pharynx is the great carburetor of beauty.” And then more about producing the vowels, “tall, not horizontal, not forward.”

Singing in his rich, even, attractive but not large baritone, Pursell repeated the phrases, but now getting a new ironic twist to the word galante, more bravado and arrogance in the characterization, Hampson demonstrated impressively in short bursts of singing and vocalizing. Finally came the complete run-through and Pursell’s singing of it and characterization were clearly much finer, winning a rousing round of applause.

At the piano for all three singers, was the Conservatory’s master of accompanying, Timothy Bach — exact, light, even in touch, and always on cue after the interruptions for the spot-on resumptions.

Hampson shared many fundamental ideas. “Opera is not about plots. It’s about dilemmas, emotion.” He described its three dimensions: 1. “What is it about; the spiritual element, the architecture. 2. The emotional aspect — very important for the singers — the language, the costumes, what that character would never say, what makes comedy funny? 3. The component of energy, form and balance.”

Hampson on his role as a teacher: “To sharpen their garden tools so that they can grow their own gardens ... It’s all about how you sing ... Don’t sing out to them, sing for them ... Make them come to you. Think, ‘We want to be in your life.’”

Other basic principles he gave included a description of his role as a teacher, “to sharpen their garden tools so that they can grow their own gardens.” He later said, “If you sing for approval, go home. It’s all about how you sing.” That tied in with the instruction he gave the soprano Amina Edris, an attractive, 24-year-old from New Zealand: She should not sing to the audience, but sing in such a way as to bring the audience to her. “Don’t sing out to them, sing for them. Everything about your singing is here” (pointing to her person) “Make them come to you. They think, ‘We want to be in your life.’”

“We are listening to someone, not listening to a voice,” he said. “Most people don’t understand, but they get it.”

More maxims: “Discipline is the ordering of the random.” “It’s like playing golf, about the reduction of error.” And several times he made reference to bel canto as not just beautiful singing but “singing more theatrically.”

With Edris, singing “Qui la voce …Vien, diletto” (Bellini’s I Puritani, her voice, clear, focused, but contained, spun out the lyric line nicely. Hampson concentrated on her straightening up her spine, by leading her walking backwards while singing. She allowed that the effect was in the “flow.” He focused on getting her to project more meaning and character, and it worked. With the aria’s lively second half, the cabaletta the last time, her singing was freer. She swept through it with more confidence, over the top note (still tight) and through the ornate run. The payoff.

Finally came Spencer Dodd, tall, thin, a baritone with a brighter sound and a moderate dynamic range singing “Hai già vinta la causa,” the Count’s aria of frustration and anger from Mozart’s Le nozze di Figaro. Those were the qualities that Hampson got him to bring out better, as well as the Count’s sense of self- importance, the fact that he’s not very bright and — a different idea — that he really feels love for Susanna. Again, Hampson worked on vowel sounds, giving brilliant, brief demonstrations. Unintimidated by that as I would have been, Dodd caught a lot more of the Count’s character and got his body straightened up, discontinuing his initial, busy gesturing. It was also a much improved performance.

The audience then left, most also improved in their awareness of the art of singing and presumably remembering to turn on their cell-phones.