Add “historian and scholar” to the catalogue of credentials preceding Marcus Shelby’s name.

The San Francisco-based bandleader, bassist, composer, arranger, educator, activist, chronicler of blues music, father, devoted partner, artist-in-residence with the Yerba Buena Gardens Festival, artistic director of the Marcus Shelby Orchestra, holder of a position on the San Francisco Arts Commission, performer (and composer) of the score for Tony-nominated performer/playwright/professor Anna Deavere Smith's new production of Notes from the Field, the play that just finished a three-month, sold-out run off Broadway at New York City’s Second Stage Theater, and … well, you get the idea.

Or, you get half the idea, because there’s also the man who silently suffers an hour in a Bay Area traffic jam for an in-person interview. Upon his arrival, he speaks during the next 90-plus minutes more about the tragedy of young black men in prison and the marvels of working with Smith than about himself and his music. In addition to composing a large body of work for his 15-member orchestra and Bay Area theater, film, and dance productions, the 50-year-old musician directs a teen jazz band at Community Music Center in the Mission, works with the Equal Justice Society, and regularly visits the kids in San Francisco Juvenile Hall.

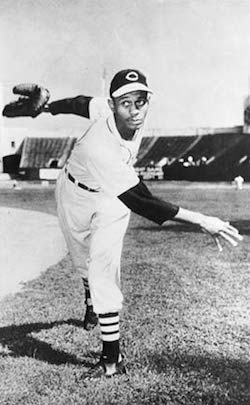

“I just came from juvenile hall,” he says, forgetting bad traffic and zeroing in on the black lives that matter and represent more than just a national movement to him. “These kids are about 14-years-old. I was surprised they knew who Satchel Paige was.”

Shelby’s current project, Blackball: The Negro Leagues and the Blues, is a Yerba Buena Gardens Festival commissioned oratorio for big band orchestra, four-part vocal ensemble, and vocal trio featuring a pitcher, catcher, and announcer. The piece, set to premiere in fall 2018, will receive work-in-progress previews during 2017. Two already scheduled at Cafe Stritch (March 4, April 16) include preshow lectures on the parallel histories of the American Negro Leagues, the blues, Jackie Robinson, and segregation/integration. Shelby will appear with a quintet to perform excerpts of the new work.

It’s likely that his talk will include mention that Satchel Paige was about the same age as the young people Shelby visits, when the legendary Negro League and MLB pitcher found his passion for baseball. And like them, he was serving time in a juvenile detention center or “reform school,” as it was known at the time. “To have that story to tell is useful. The kids see it isn’t the end for them.” And when he tells them that Louis Armstrong similarly picked up a trumpet and his life’s purpose while in a reform school in the early 1900s, beginning a journey that led Armstrong to become one of the 20th century’s most influential musicians, Shelby launches a narrative that connects America’s favorite pastime with his greatest loves, the blues and African American history.

“I’ve been trying to create my soundtrack by writing about my history, ever since I became a composer,” he says. “I use music to reveal how we got to where we are; to reflect history in the most positive and truthful way.”

For the new work, as for previous projects that include Soul of the Movement, a musical suite on Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement, and Harriet Tubman, a work based on the life of the well-known freedom fighter, Shelby does deep research. Some of it’s lighthearted — he’s a devoted S.F. Giants’ fan and draws from his personal history as an athlete who attended Cal Poly to study electrical engineering on a basketball scholarship before music swept away his NBA dreams. “In the ’70s, I saw black players in the major leagues, so it was a big part of me.”

As he studied the Negro League, the industry intrigued him. “I’ve just been reading, reading, reading. It became about more than just the sport, it became the entrepreneurship of the Negro Leagues.” The 1896 Plessy versus Ferguson Supreme Court decision that upheld state racial segregation laws for public facilities based on the “separate but equal” doctrine — Shelby generously but pointedly refers to it as “a gentleman’s agreement” that kept major leagues color-free — cemented the Negro League’s future for decades. “For 60 years, it became one, if not the biggest black business in the United States,” says Shelby.

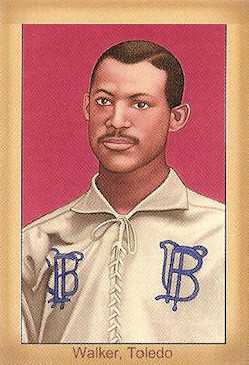

Simultaneously, the world of jazz exploded with innovative and talented African American musicians in the first half of the 1900s. In many ways a foreshadow of the 1950s and 60s civil rights movement, blues musicians and ball players as far back as 1884 and Moses Fleetwood Walker, the first black player in MLB, and Jackie Robinson, who broke the MLB color barrier for a second time in 1947, used physical power and celebrity to change society. Shelby says that once the blues became “an organized art form,” the musicians had much in common with black baseball players of the time. Traveling by bus through segregated communities, music and baseball nevertheless sustained African American lives, hopes, and cultural memory.

The associations taken into composition, Shelby can imagine a trumpet connecting Armstrong to Paige; perhaps the parallels between American Negro League catcher Josh Gibson and saxophonist Charlie Parker creating another instrument-ball player matchup. “I imagine it like a dance piece. It’s going to premiere outside; I’ll use the physicality of the game where it applies.”

Because many players in the league were from the Dominican Republic or Cuba, early Afro-Cuban musical influences are likely. An effort to capture the literal sound of the game also informs the work: the “thwack” of a bat hitting a ball, the “swish” of air disturbed by fast-moving objects, the accelerated pace and syncopated rhythms of a radio broadcast, a pitcher taunting a batter in song form, or the diamond shape of the field determining the oratorio’s melodic, harmonic, and overall structure. “Then there’s the unknown. That’s almost more exciting than what I already know,” says Shelby.

His enthusiasm to enter the unknown is at the root of the four-year collaboration he and Smith have enjoyed. During the six-nights-a-week, 50-show New York run, Shelby says that Notes changed dramatically from the early versions staged in San Francisco in 2014. “We have new video, sliding panels, different furniture. Anna localized the piece. Wherever we go, she uses the characters from the area.”

Notes addresses the school-to-prison pipeline that pushes children out of classrooms and into the criminal justice system. Smith performs solo portraits based on hundreds of interviews she conducted with students, educators, parents, police, medical professionals, community activists, and more. Shelby is onstage playing double bass — a shadow character who, in the early versions, was ground support for the melodrama but whose role has become more integral. “We’ve found moments where I’m like the church choir, the ‘amen,’ the ‘mm-hmm.’ I tightened the three themes that reoccur. The themes push and enhance the mood and keep the moments moving along.”

Listening is a big component. “There’s a lot of space: (Anna) may move faster or slower,” he says. “I had to forget how it happened the night before. I had to remember what’s been happening over time and support that.”

The performance one night after the presidential election, he says, was “like a funeral.” Unlike previous shows that had drawn celebrities — Oprah Winfrey, Chris Rock, and others — this audience didn’t laugh at the Notes’ humorous moments. “It was like they’d been hit with a piece of wood. Even the powerful, uplifting moment of reconciliation at the end was different. It was a dark, dark show.”

But overall, Shelby’s takeaway from the experience is joyful. The lightly muted, warm tone of a bass might lack the brighter dynamics of a soaring trumpet, but its weighted buoyancy anchors the harmony and playing notes on every beat grounds the wide-ranging inflection of Smith’s text. Double stops add texture and emphasis. “She never told me once, ‘Do this, don’t do that.’ Her positive feedback, you just feel it. You know, she was still working on this show right up to the first show. Every performance is like the first one, the most important one. I’ve never seen a woman work harder.”

Shelby says his blues-inflected compositions are a shortened version of a complicated story: haiku told with notes that serve as a musical mirror to Smith’s portraits. Aiming for the call-and-response of the genre and the black Baptist Church sermons he recalls from childhood, he uses dissonant chords, double stops, and ostinato to create a “water and hose” effect. “It builds, then when you straighten out the hose, there’s this sense of release.” Freedom of expression is the domain of every blues singer, he insists. “A voice’s timbre is one of the most unique things a person has.” Applying instrumental harmony extends the relationships between a voice’s “happy mask and sad mask.” The high-low duality is a critical component in presenting a realistic portrayal of the human condition.

A February 2017 run of Notes in Santa Monica was abruptly cancelled at the end of 2016. Shelby doesn’t know all the details, but guesses that the show’s evolution meant the current version didn’t suit the venue. While he waits to find out if more East Coast shows have been arranged, he’s played for Living Jazz’s January 15 In the Name of Love: Marvin Gaye Tribute at the Scottish Rite Theater in Oakland and upcoming Bay Area appearances with his orchestra and quintet.

And there are the weekly visits to juvenile hall, where he sees “moments to invigorate” with music. “But often, I don’t even play my double bass. I have it, something that’s like my weapon, used to build things up instead of destroy things. I speak of love of instrument, of purpose. They know that’s my baby and it’s how I combat challenges.” Prisons, he says, don’t rehabilitate people or inspire loving activism. But music does.

Read about Marcus Shelby’s upcoming dates on his website calendar.

Header photo of Marcus Shelby courtesy of BayTaper.com.