Pity the opera lover who wants to put his head in the sand. In the same week that the San Francisco Conservatory of Music’s production of Benjamin Britten and Ronald Duncan’s The Rape of Lucretia addressed sexual exploitation and violence by those in power, San Francisco Opera’s world premiere of John Adams and Peter Sellars’s Girls of the Golden West excoriated the racism and misogyny at the core of the American Dream, California style. Unless you turned off the news and locked yourself indoors, there was nowhere to hide.

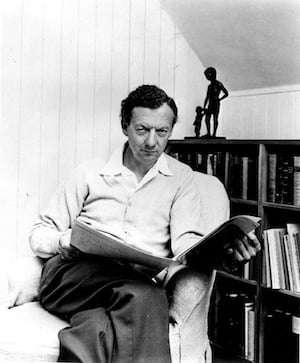

Britten’s ability to communicate the terrible assault by Etruscan Prince Tarquinius on Lucretia, faithful wife of General Collatinus, has lost none of its searing relevance. Composed in 1946 and designed for smaller forces, its power to make inescapable the consequences of violence is even more emotionally devastating than Adams’s.

Many of the singers in the first cast (seen Dec. 8) — only the three soldiers and two supernumeraries returned on Dec. 10 — succeeded nobly. Britten and Duncan’s conception of the legend of the rape of Lucretia — an act that was later seen as a catalyst for Roman rebellion against the oppressive Etruscan king — relies heavily on the impact of the first two characters onstage, the Male Chorus (Ricky Garcia) and Female Chorus (Esther Tonea). So moved is this pair by Lucretia and Collatinus’s fates that they transcend their traditional Greek role as commentators by occasionally touching other characters and trying to influence their actions.

SFCM could hardly have cast the roles better. Garcia’s tenor has an innate, heart-touching passion, and his presence is sympathetic. If he has the power to fill a large house, there’s great potential there. Tonea’s upper range when she sings out conveys a power that suggests dramatic soprano territory. When her voice was fully controlled, as it was in Act II, it impressed as a special instrument that wanted only for more expressive color on bottom.

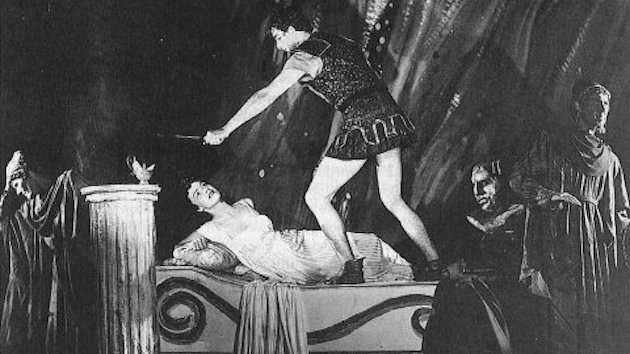

Of the three soldiers, Edward Laurenson (Tarquinius) and Jorge Ruvalcaba (Junius) stood out for their dramatically convincing portrayals. Laurenson is blessed with the ability to look both handsome and unstoppably mean while singing with unflinching power. Only in Act II, when he occasionally lightened his voice, did he betray hints of a vocal warmth at odds with such a dastardly character.

Ruvalcaba had less to sing, but his intense vocal and dramatic presence made their mark. Brandon Bell’s voice (Collatinus) is less focused than his colleagues’ in the lower midrange and, at this point in his development, less affecting, but his sympathetic presence and voice when confronted with his wife’s assault made their mark. What a shame that costume coordinator Robert Horek couldn’t do better than dress the men in dancers’ leg warmers.

Tenderness made its mark in the student orchestra’s depiction of the lovely sleep music that precedes Tarquinius’s stealth-like entrance and brutal, alcohol-fueled rape. Under conductor Curt Pajer, the contrast between peace and the violence that leaves it in shreds was profound. Elsewhere, individual instrumental lines sometimes lacked conviction, as though players had not yet pieced the entire orchestral fabric together and understood the message behind their individual notes. But when passions reached their height, the orchestra triumphed.

Jessie Barnett (Bianca) and Meagan Rao (Lucia) were superb as Lucretia’s maids. The sadness and gravity of Barnett’s voice and appearance spoke volumes — I wonder if she has the power for lead roles — while Rao’s exceptionally pure soprano was an ear opener. Britten’s writing revealed neither the upper limits of Rao’s range nor her facility with coloratura, but her charming sweetness and youthful innocence screamed Zerbinetta or the high-voiced Naiad in Strauss’s Ariadne auf Naxos. In fact, her only limitation was that she came across as so lovable and naïve that she seemed a bit clueless post-rape. Regardless, both women could go far.

Lucretia is a tough role. Conceived for contralto Kathleen Ferrier, whose soul-touching ability to sing from the holy depths of her being has since been approached by only two mezzo-sopranos (Janet Baker and Lorraine Hunt Lieberson), the role demands an artist who can leave an audience in tatters. Molly Boggess made lovely sounds, but her instrument lacked the depth essential to conveying Lucretia’s plight. When orchestra and other characters got extremely animated, she was overwhelmed. In addition, while her beauty shone when she let her hair down before the rape scene, Grisel Torres’s Act I lighting cast her as an untouchable ice princess.

There were several missteps in Heather Matthews’s direction. Lucretia’s suicide is most certainly not modeled after a character in some 19th-century bel canto operatic mad scene. Alas, Mathews and Boggess made Lucretia’s climactic appearance into a ridiculous, wide-eyed cross between Lucia and Ophelia. The music cried in pain, but the portrayal screamed preposterous melodrama.

Another misstep was to end the performance by illumining the cross in Peter Crompton’s otherwise nondescript set. Britten and Duncan may have chosen to emphasize the Christian perspective in André Obey’s play — Britten was hardly the first homosexual to embrace the very religion that oppressed him — but this final visual cue diluted the impact of a message whose universality transcends religious dogma. It is to the credit of all involved that the performance nonetheless left the audience shaken by humanity’s seemingly limitless capacity for the contradictory opposites of compassion and cruelty.