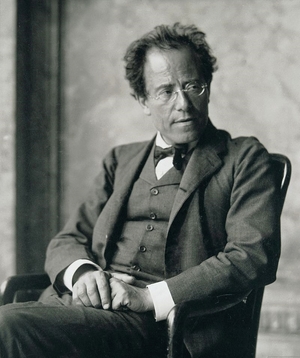

Sonoma State University students in graduation robes posed for pictures and hugged each other at the stone gates last Sunday afternoon, mirroring the prolonged farewells within the university’s Green Music Center. There, with an unforgettable performance of Mahler’s Ninth Symphony, Bruno Ferrandis bade adieu to the Santa Rosa Symphony after a dozen years at the helm. Some audience members took photographs to commemorate the event, but my most vivid remembrance is of the beautiful sonorities and hushed expectancy of the symphony’s closing moments.

At some 80 minutes, the Mahler could have constituted the entire program, but a wine-sipping intermission was obligatory, so Ferrandis and company opened with Temporis, a 2015 concerto for cimbalom by the Czech composer Michal Rataj, with cimbalom soloist Jan Mikušek.

The concert cimbalom is a trapezoidal Eastern European instrument that resembles a horizontal harp, with strings that are struck by mallets, plucked with fingers, or otherwise set to vibrating. The sound that emerges is reminiscent of plucked piano strings, with considerable resonance but not much volume.

Rataj’s score harnessed these resonances to the orchestra by setting most of the dynamics at pianissimo and alternating orchestral bursts with cimbalom solos. The resulting sound was often ethereal, tenuous, and ghostly. At times, the cimbalom sounded like bells, but more often like a cloud of notes gently settling over the stage.

While the acoustics were striking, the underlying musical form was elusive. Forward motion and thematic development were hard to detect under the obscuring sonic mist. The conclusion was memorable, however. First, Mikušek sang a wordless phrase, and then he seemed to make all the cimbalom’s strings resonate at once, erecting a veritable wall of sound that slowly dissipated. He followed Temporis with an encore of more traditional cimbalom repertoire, singing the Czech folk song “Up on the Hill” while accompanying himself on his instrument. The blend was irresistible.

Cimbaloms were popular in Mahler’s day, but he didn’t include any in the massive 90-person orchestra required to play his final symphony. Virtually every section of the ensemble increased in size, nowhere more so than the woodwinds, whose numbers doubled. Pianissimo markings were abundant, but so were thundering crescendos, triple fortes, and — more than anything else — the composer’s premonitions of his impending death.

The Ninth opens minimally in the cellos and horns, but their sound soon evolves into a full-throated roar marked by a descending two-note motive. Ferrandis was by turns restrained, animated, and energetic as he guided the players through the opening movement’s many twists and turns. A feeling of expectancy suffused the playing, even as harmonic resolution kept receding in the distance.

The challenge of the first movement is to keep the story moving forward and not let it get buried by the incessant barrage of notes. Here Ferrandis and the players succeeded admirably. They played each of the many climaxes at full force, but they never let up in the ensuing moments of quietude. One could hear the sounds of doom in the woodwinds and brass as the orchestra finally wound down with a series of exquisite solos from the principal horn, violin, oboe, and harp.

In the second movement, the mood changed abruptly to a country dance in three-quarter time. The playing was jaunty and the oft-repeated trills impressive, but the tempo often dragged.

In contrast, the third movement was a whirling dervish, with frenzied playing all around. The movement opens with a simple three-note motive that is handed from section to section, like a fugue. The complexity and tension mounted until a beautiful solo from the principal trumpet

slowed everyone down. Ferrandis guided the orchestra expertly through the sudden change and kept pushing through the inexorable build-up to the presto closing.

Such an invigorating ending might satisfy a lesser composer, but Mahler sets all the preceding movements aside to embark on his last, one of the most gorgeous in the repertoire. The violins opened with a magisterial melody, followed by a superb horn solo as the violins hovered above in nearly perfect intonation. A sense of finality crept in as all the strings joined in the lament. The moment was so spine-tingling that the elderly couple next to me suddenly grasped each other’s hands.

After the strings relented, the woodwinds took over, slowly building upward with a series of commendable solos. The entire orchestra joined in for a triple-forte climax, immediately followed by a triple piano. A hush descended on the audience as the symphony gradually faded away, marked by an elegiac solo from the principal cellist and a last word from the violas. Ferrandis extended the silence for a long moment, gathering his composure before bidding farewell to the cheering crowd.