We may read occasional pronouncements and meditations in the intellectual or mass media about the end of jazz in America, but Los Angeles’s nearly-eponymous Angel City Jazz Festival refuses to accept the verdict. Founded in 2008, Angel City is a scrappy, progressive jazz festival that materializes — as per the title of Ralph Burns’s most famous song — in the “early autumn” in various spaces around the Southland.

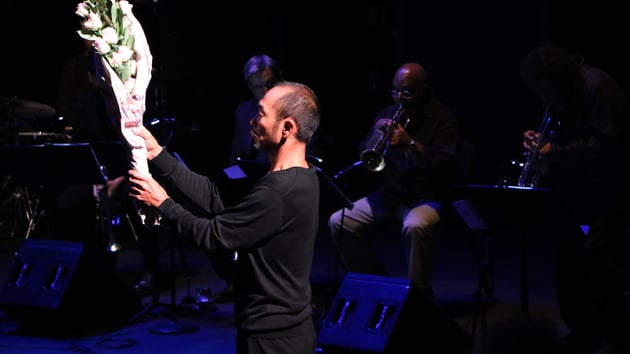

You won’t find on this year’s brochure any posthumous tribute concerts to giants of the past; that’s fodder for the jazz-is-dead crowd. This year, in a break from its usual pattern, there was no overarching theme tying the concerts together. But there was what founder-executive director Rocco Somazzi calls Angel City’s most ambitious production yet — the world premiere at REDCAT on Sunday, Oct. 14, of the Rosa Parks Oratorio by the avant-garde composer-trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, who is a story in himself.

Smith is currently enjoying a prolifically creative Indian summer unlike that of any other major jazz figure in their 70s, past or present. One large work after another has been pouring out of him over the last decade, often with a political or environmental agenda attached. Indeed, the Rosa Parks Oratorio could be considered a follow-up to Smith’s civil rights movement epic Ten Freedom Summers, which at over 4 ½ hours in length may well be the longest jazz-based work ever written.

This new piece is a mere 76 ½ minutes long — matching the composer’s age — and like most of Smith’s recent material, falls in the netherworld between freeform jazz and contemporary classical music (he prefers the term “creative music”). The work contains seven songs for three singers (Carmina Escobar, Karen Parks, Min Xiao-Fen), each of whom represents Rosa Parks. There are also what Smith calls four “vision dances” (danced by Butoh-influenced dancer/choreographer Oguri) that are supposed to expand upon the meaning of the songs.

As in Smith’s performance of America’s National Parks three weeks ago at the Monterey Jazz Festival, a continuous video was shown, juxtaposing views of the musicians playing in real time with abstract shapes and old photographs and artifacts from Parks’s life. Especially fascinating was a set of fingerprints from Parks’s arrest in Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955, the event that essentially launched the modern civil rights movement.

Smith’s unorthodox forces centered upon two quartets deployed opposite each other — the one on the left being a conventional string quartet, the one on the right a quartet of trumpets. Smith’s regular drummer Pheeroan akLaff contributed loose-limbed, free jazz drumming in sparing amounts, and Min Xiao-Fen, who has been working on and off with Smith for 20 years, doubled on Chinese pipa, adding beautiful, rippling obbligatos to the mix.

The music seemed to suspend the notion of time, rolling along in a slow-motion procession even when the musicians were playing rapid bunches of notes. Smith got our attention immediately with a dissonant blast from the four trumpets underpinned by a burst of free drumming. All along the way, the textures kept changing, with different combinations of timbres holding one’s interest while maintaining the meditative mood. At its best, the string quartet music had an austere beauty, whether waxing lyrically or engaging in stringent dissonance. In the few instances where everyone was going at once, the collective sound dazzled the senses, helped by REDCAT’s excellent amplification.

On top of all of that were the eloquent musings of Wadada himself on his horn. He produces the loneliest muted trumpet sound this side of Miles Davis, pointing the bell of his horn toward the floor like Miles did. The notes yearn and scorch and seem all the more powerful by the silences separating them.

Since no libretto was provided and there was only the skimpiest of program notes about the oratorio (about five lines worth), one could only make out the barest outline of what Rosa Parks meant to Smith and the world at large through the words of the singers. But maybe it wasn’t necessary to know, for Wadada’s trumpet alone spoke volumes about his depth of feeling for a black history icon. Music can do that.